-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Masakazu Matsuda, Shohei Yoshiya, Ippei Kawada, Sota Nakamura, Kazuhiro Tada, Kensaku Ito, Hidenori Koso, Yosuke Kuroda, Fumitaka Yoshizumi, Kentaro Iwaki, Shoji Hiroshige, Yo-ichi Yamashita, Hideya Takeuchi, Tomoharu Yoshizumi, Kengo Fukuzawa, Small intestinal metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed and resected as intestinal obstruction caused by a foreign body, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf679, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf679

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hematogenous metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) to the small intestine are rare. In most cases, hematogenous metastasis is symptomatic, including perforation or bleeding, and the prognosis is poor. A 63-year-old man had lower right abdominal pain, and small intestinal obstruction due to chronic inflammation of the foreign body was suspected on computed tomography. Blood tests revealed elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). He had undergone four surgeries for HCC. Conservative treatment was administered, but there was little improvement. A segmental resection of the small intestine was performed. A type 2 tumor was found in the resected specimen, and pathological examination led to a diagnosis of HCC metastasis in the small intestine. He survived without recurrence for 10 months after surgery. When a patient with a history of HCC treatment develops intestinal obstruction or intussusception, it is necessary to consider the possibility of small intestinal metastasis, especially if there is an increase in AFP.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is rare, occurring in 4%–12% of autopsy cases, with small intestinal involvement being particularly uncommon [1, 2]. Over half result from direct invasion, mainly to the stomach, whereas hematogenous metastases are relatively uncommon [1]. Symptomatic cases are usually detected by bleeding, perforation, ileus, or intussusception, and often have a poor prognosis because metastases to other organs are already present when symptoms appear [2]. Preoperative diagnosis is challenging [1]. In most cases, surgery is performed under the suspicion of a gastrointestinal disorder, with the final diagnosis being made after pathological examination.

Case report

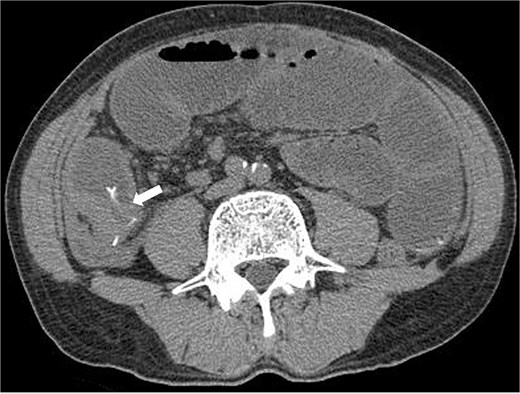

A 63-year-old man presented with recurrent right lower abdominal pain. Blood tests showed mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), dehydration, and a high alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) of 2659 ng/ml. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a high-density area in the small intestine of the right lower abdomen, which was suspected to be a foreign body, with circumferential wall thickening in the same area (Fig. 1). The intestinal tract on the oral side of the area was dilated, and small intestinal obstruction due to chronic inflammation caused by the foreign body was suspected.

Preoperative CT revealed a high density area in the small intestine of the right lower abdomen, which was suspected to be a foreign body, and a circumferential wall thickening in the same area. The intestinal tract on the oral side of the area was dilated, and small intestinal obstruction due to chronic inflammation caused by the foreign body was suspected.

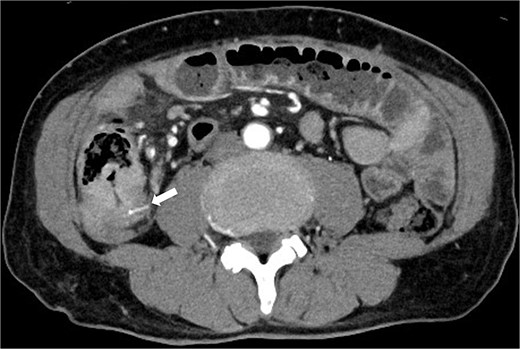

Three months prior, the patient presented with similar symptoms. CT revealed a high-density area in the same region that was thought to be a foreign body, identical to the foreign body seen on the preoperative CT, and circumferential wall thickening (Fig. 2). Although AFP was 1507 ng/ml consistent with 1400–1600 ng/ml, the findings of recurrence had not been detected in internal medicine follow-up. Ileal penetration, rather than perforation, caused by a foreign body was suspected. Since there were no peritoneal signs, conservative treatment was initiated, leading to temporary symptom relief.

CT taken 3 months before surgery revealed a high-density area in the small intestine of the right lower abdomen that was thought to be a foreign body identical to the foreign body seen on the preoperative CT scan, as well as circumferential wall thickening.

The patient achieved a sustained virological response to hepatitis C virus 9 years prior and had undergone partial hepatectomies twice for HCC 8 and 7 years prior, a local gastrectomy for gastric dissemination 6 years prior, and a resection of peritoneal dissemination 5 years prior.

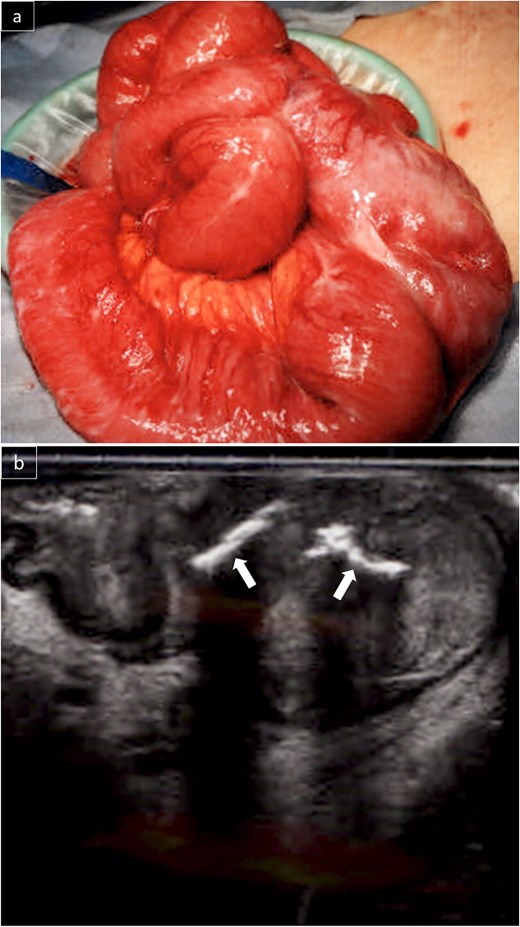

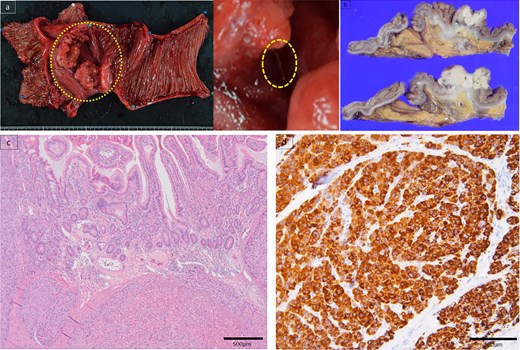

Due to persistent symptoms after 11 days of conservative management, surgery was performed. The small intestine was adherent in the right lower abdomen, with no obvious serosal abnormalities (Fig. 3a). Intraoperative ultrasonography identified a linear hyperechoic structure consistent with the foreign body on CT (Fig. 3b). A partial resection of the small intestine was performed. Grossly, a type 2 tumor containing a wire-like foreign body was identified (Fig. 4a). Pathological examination revealed that the tumor was predominantly located from the muscularis propria to the subserosa (Fig. 4b), with atypical cells present in a pseudoglandular duct-like fashion (Fig. 4c). No vascular invasion was observed in previous surgeries, and pathology from this surgery also showed no vascular invasion. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the tumor was hepatocyte-positive (Fig. 4d), CK20 negative, and CDX2 negative. The tumor was diagnosed as a small intestinal metastasis of HCC. Postoperatively, the patient showed anastomotic stenosis, but was discharged from the hospital on the 17th postoperative day. Follow-up CT showed no recurrence 4 months after surgery. The patient survived 10 months postoperatively without recurrence, with AFP significantly decreasing to 213 ng/ml 10 months after surgery.

The small intestines in the right lower abdomen were lumped together, and no lesions were exposed on the serosal surface (a). Intraoperative ultrasonography revealed a linear hyperechoic area in the mass that appeared to be a foreign body on CT (b).

Specimen showed a type 2 tumor in the small intestine with a foreign body, such as a stuck wire (a). Pathological examination revealed that the tumor was predominantly located in the muscularis propria of the subserosa (b). Atypical cells existed in a pseudoglandular duct-like manner (c). Immunohistochemistry findings elucidated hepatocyte positive (d).

Discussion

HCC is invasive, and extrahepatic metastasis to the lungs, lymph nodes, or adrenal glands is often observed; however, metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract is rare [1, 2]. The modes of metastasis are 66.7% direct invasion, 16.7% hematogenous metastases, and 5.6% peritoneal dissemination [1, 6]. Gastrointestinal metastasis is often caused by direct invasion due to adhesions to the serous surface of the adjacent gastrointestinal tract, and is most common in the stomach. Hematogenous metastases to the small intestine are rare [1, 2, 6]. Hematogenous metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract may be caused by tumor embolization in the portal venous system, which spreads into the portal bloodstream and the gastrointestinal tract [1].

Small-intestinal metastases are usually asymptomatic and are often discovered during postmortem autopsies [1]. Symptomatic cases are often detected by bleeding, perforation, ileus, or intussusception [8]. Vascular invasion is an independent prognostic factor [9], and the disease is often accompanied by metastases to other organs when symptoms appear; therefore, long-term outcomes are generally poor [2, 8].

Seven cases of small intestinal metastasis from HCC were identified through a PubMed search using the keywords “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “small intestine”, and “metastasis” (Table 1) [1–7]. Four patients had abdominal pain as the main complaint, and CT showed masses and intestinal intussusception in four cases. Most patients had metastases to other organs, such as the lungs and adrenal glands. Five patients had viral liver disease in the background liver. Only one patient was diagnosed based on imaging findings [4]. In our case, although the AFP level was elevated, we initially suspected a gastrointestinal disorder rather than small intestinal metastasis of HCC, given the extreme rarity of such metastasis and the presence of the CT findings suggestive of a foreign body. Furthermore, our hospital has no positron emission tomography-CT and the patient needs to discharge to undergo this examination. But the patient could not discharge due to his condition of a disease. High AFP levels may be a clue for detecting small intestinal metastases. In cases of HCC presenting with intestinal obstruction or intussusception, small intestinal metastasis should be suspected, especially with elevated AFP levels.

Seven cases of small intestinal metastasis from HCC were identified through a PubMed search using the keywords “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “small intestine”, and “metastasis”.

| Author Year . | Age Sex . | Symptoms . | CT . | Other metastases . | AFP (ng/ml) . | Background liver . | Duration since last treatment . | Prognosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim HS 2006 [1] | 65 M | Abdominal pain | Tumor Intussusception | Bone Lymph node | High (629) | HBV+ | 2 months | |

| Iwaki K 2008 [3] | 60 M | No symptom | – (discovered during surgery) | Lung Spleen | HCV+ | 4 months | ||

| Yoo SW 2017 [4] | 43 F | |||||||

| Tsukamoto T 2019 [5] | 71 M | No symptom | Intussusception | Fat tissue Retroperitoneal tissue Lung, Adrenal | 22 months | |||

| Suzuki N 2020 [2] | 75 M | Abdominal pain | Perforation | Lung | Normal (2.2) | Alcoholic liver damage | 1 month | |

| Mashiko T 2020 [6] | 71 M | Abdominal pain Vomiting | Tumor Intussusception | Adrenal Peritoneum | HBV+ | 2 months | Adrenal metastasis 78 months after surgery Survival for 82 months | |

| Hong YM 2024 [7] | 75 M | Anemia | Tumor | Normal (1.9) | HBV+ | 2 years | ||

| Our case 2024 | 63 M | Abdominal pain | Ileus Foreign body | Stomach Peritoneum | High (2659) | HCV+ | 5 years | Survival for 10 months |

| Author Year . | Age Sex . | Symptoms . | CT . | Other metastases . | AFP (ng/ml) . | Background liver . | Duration since last treatment . | Prognosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim HS 2006 [1] | 65 M | Abdominal pain | Tumor Intussusception | Bone Lymph node | High (629) | HBV+ | 2 months | |

| Iwaki K 2008 [3] | 60 M | No symptom | – (discovered during surgery) | Lung Spleen | HCV+ | 4 months | ||

| Yoo SW 2017 [4] | 43 F | |||||||

| Tsukamoto T 2019 [5] | 71 M | No symptom | Intussusception | Fat tissue Retroperitoneal tissue Lung, Adrenal | 22 months | |||

| Suzuki N 2020 [2] | 75 M | Abdominal pain | Perforation | Lung | Normal (2.2) | Alcoholic liver damage | 1 month | |

| Mashiko T 2020 [6] | 71 M | Abdominal pain Vomiting | Tumor Intussusception | Adrenal Peritoneum | HBV+ | 2 months | Adrenal metastasis 78 months after surgery Survival for 82 months | |

| Hong YM 2024 [7] | 75 M | Anemia | Tumor | Normal (1.9) | HBV+ | 2 years | ||

| Our case 2024 | 63 M | Abdominal pain | Ileus Foreign body | Stomach Peritoneum | High (2659) | HCV+ | 5 years | Survival for 10 months |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus, HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Seven cases of small intestinal metastasis from HCC were identified through a PubMed search using the keywords “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “small intestine”, and “metastasis”.

| Author Year . | Age Sex . | Symptoms . | CT . | Other metastases . | AFP (ng/ml) . | Background liver . | Duration since last treatment . | Prognosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim HS 2006 [1] | 65 M | Abdominal pain | Tumor Intussusception | Bone Lymph node | High (629) | HBV+ | 2 months | |

| Iwaki K 2008 [3] | 60 M | No symptom | – (discovered during surgery) | Lung Spleen | HCV+ | 4 months | ||

| Yoo SW 2017 [4] | 43 F | |||||||

| Tsukamoto T 2019 [5] | 71 M | No symptom | Intussusception | Fat tissue Retroperitoneal tissue Lung, Adrenal | 22 months | |||

| Suzuki N 2020 [2] | 75 M | Abdominal pain | Perforation | Lung | Normal (2.2) | Alcoholic liver damage | 1 month | |

| Mashiko T 2020 [6] | 71 M | Abdominal pain Vomiting | Tumor Intussusception | Adrenal Peritoneum | HBV+ | 2 months | Adrenal metastasis 78 months after surgery Survival for 82 months | |

| Hong YM 2024 [7] | 75 M | Anemia | Tumor | Normal (1.9) | HBV+ | 2 years | ||

| Our case 2024 | 63 M | Abdominal pain | Ileus Foreign body | Stomach Peritoneum | High (2659) | HCV+ | 5 years | Survival for 10 months |

| Author Year . | Age Sex . | Symptoms . | CT . | Other metastases . | AFP (ng/ml) . | Background liver . | Duration since last treatment . | Prognosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim HS 2006 [1] | 65 M | Abdominal pain | Tumor Intussusception | Bone Lymph node | High (629) | HBV+ | 2 months | |

| Iwaki K 2008 [3] | 60 M | No symptom | – (discovered during surgery) | Lung Spleen | HCV+ | 4 months | ||

| Yoo SW 2017 [4] | 43 F | |||||||

| Tsukamoto T 2019 [5] | 71 M | No symptom | Intussusception | Fat tissue Retroperitoneal tissue Lung, Adrenal | 22 months | |||

| Suzuki N 2020 [2] | 75 M | Abdominal pain | Perforation | Lung | Normal (2.2) | Alcoholic liver damage | 1 month | |

| Mashiko T 2020 [6] | 71 M | Abdominal pain Vomiting | Tumor Intussusception | Adrenal Peritoneum | HBV+ | 2 months | Adrenal metastasis 78 months after surgery Survival for 82 months | |

| Hong YM 2024 [7] | 75 M | Anemia | Tumor | Normal (1.9) | HBV+ | 2 years | ||

| Our case 2024 | 63 M | Abdominal pain | Ileus Foreign body | Stomach Peritoneum | High (2659) | HCV+ | 5 years | Survival for 10 months |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus, HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Treatment options for recurrent HCC include resection, local therapy, TACE, chemotherapy and liver transplantation [10–12]. Although, especially in extrahepatic recurrence, chemotherapy is the first choice, the efficacy of resection is also referred in consensus statement. Therefore, aggressive resection may be considered for symptomatic lesions.

Conclusion

Preoperative diagnosis of small intestinal metastases from HCC is difficult. Small-intestinal metastasis should be considered when a patient with HCC develops intestinal obstruction or intussusception, particularly if there is an increase in AFP levels.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this case report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical approval

According to our institutional guidelines, ethical approval is not required for case reports.