-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Luis Francisco Llerena Freire, Majerlly Anahí Gallardo, Ivonne Carolina Córdova, Laparoscopic management of a Gharbi type II hepatic hydatid cyst after failed pair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf665, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf665

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatic hydatidosis, caused by Echinococcus granulosus, remains prevalent in endemic regions. Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment, although laparoscopic approaches have gained prominence in selected cases in the past decade. We present a case of a Gharbi-type II hepatic hydatid cyst successfully treated via laparoscopy. A 19-year-old man from a rural endemic area, presented with right upper quadrant pain. Imaging revealed a Gharbi type 2 hydatid cyst in the posterior segment VII of the liver. Laparoscopic evacuation of the cyst content was performed with strict preventive measures to avoid dissemination. The patient had a favorable outcome without complications. Laparoscopy offers a safe alternative for peripheral cysts without biliary communication and in experienced centers. Proper patient selection and technical proficiency are essential to minimize risks. This report highlights the feasibility of laparoscopic management of Gharbi type II cysts in carefully selected patients and illustrates the role of laparoscopy as a salvage strategy following failed PAIR.

Introduction

Hepatic hydatidosis is a parasitic zoonosis caused by Echinococcus granulosus, with worldwide distribution, though more prevalent in rural regions of South America, North Africa, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean [1]. The liver is the most frequently affected organ, accounting for over 60% of cases [2]. The disease often progresses asymptomatically but may present with abdominal pain, palpable mass, or complications such as rupture, infection, or biliary fistula [3].

The ultrasound classification proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO-IWGE) allows categorization of cysts into different evolutionary stages. The CE2 type represents an active, multivesicular, fertile form, with multiple viable daughter vesicles inside the mother cyst, increasing the risk of recurrence and complicating management [4]. The cyst in this case corresponded to Gharbi type II, which shows partial overlap with WHO CE2 classification but differs in imaging and structural criteria.

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment, although in recent years, laparoscopy has emerged as a safe and effective option in selected cases. Its use in CE2 cysts, however, remains controversial due to the risk of peritoneal dissemination if strict containment measures are not applied [5, 6].

Case report

A 19-year-old male patient with no comorbidities, resident of a rural area, presented with dull right upper quadrant pain for several weeks, without fever or jaundice. He reported frequent contact with dogs. He had previously undergone percutaneous PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, and Reaspiration) therapy. Three months later, due to unsatisfactory results, he was re-evaluated. Physical examination revealed deep right upper quadrant tenderness without signs of peritoneal irritation. Laboratory tests showed no relevant abnormalities; serology was positive for Echinococcus granulosus.

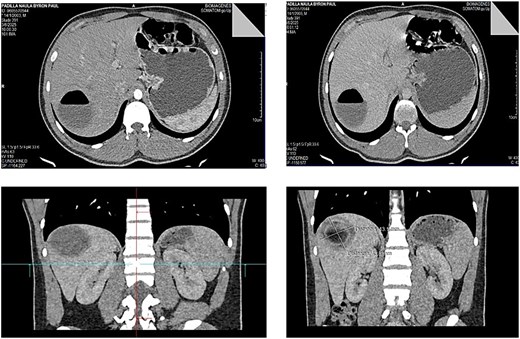

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a hydatid cyst, Gharbi type II, with an air-fluid level located in liver segment VII, measuring 5 cm in diameter and approximately 83 cc in volume. The air-fluid level was attributed to the previous puncture (Fig. 1).

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT showing a Gharbi type II hydatid cyst with an air-fluid level in segment VII of the liver, measuring approximately 5 cm in diameter.

Following multidisciplinary discussion, laparoscopic surgical management was chosen. The patient received albendazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 14 days prior to surgery.

Surgical technique

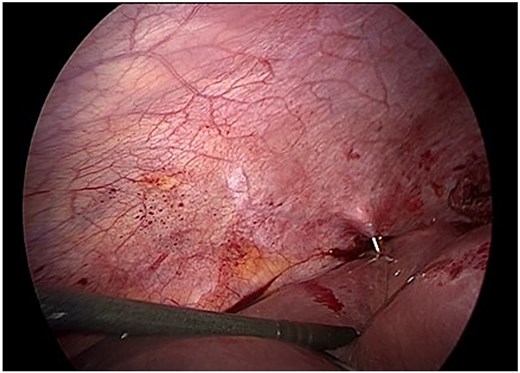

The laparoscopic procedure was performed using four trocars. The operative field was protected with gauze soaked in 17.7% hypertonic saline to reduce the risk of peritoneal dissemination. The cyst was punctured, and a scolicidal agent (17.7% hypertonic saline) was instilled into the cavity and retained in situ for 15 minutes before aspiration. A secondary suction device was used to minimize leakage (Fig. 2).

Intraoperative view of controlled puncture and aspiration of cyst contents. Gauze soaked in 17.7% hypertonic saline protects the operative field to prevent spillage.

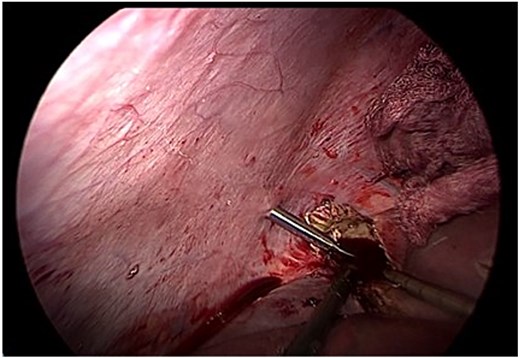

Following aspiration, the germinative membrane was carefully extracted using an endoscopic retrieval bag through a 10 mm trocar. The residual cavity was inspected with a 30° scope to detect any biliary communication (Fig. 3).

Endoscopic removal of the germinative membrane using an endobag through the 10 mm trocar. Inspection of the residual cavity was performed with a 30° laparoscope.

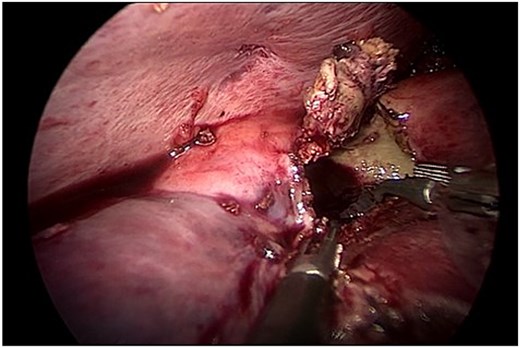

Given the size and location of the cyst, complete pericystectomy was not indicated due to proximity to major vascular structures and the absence of complications. Instead, careful evacuation of the membrane and limited resection of prominent pericystic tissue was performed, preserving liver integrity (Fig. 4). A drain was left in place due to the potential for undetected biliary communication.

Careful evacuation of cystic material and limited resection of prominent pericystic tissue. Complete pericystectomy was not indicated due to cyst size and location.

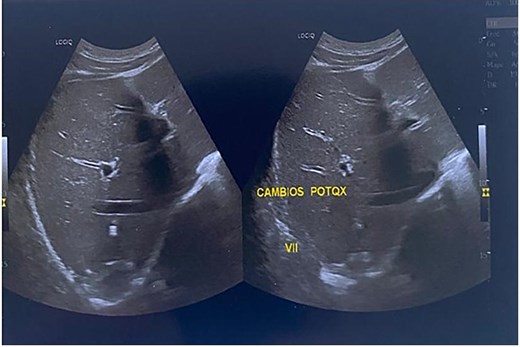

The patient had an uncomplicated recovery and was discharged on postoperative day two with no evidence of bile leakage. Three cycles of albendazole were prescribed (at intervals of 28 days with 14-day drug-free periods). The drain was removed after 15 days; no biliary fistula or residual fluid collection was detected. Follow-up ultrasound at three months showed no recurrence (Fig. 5).

Three-month follow-up ultrasound showing small linear echogenic areas in segment VII, consistent with postsurgical changes. No anechoic or recurrent cystic areas were observed.

Discussion

Managing CE2 hepatic hydatid cysts presents technical challenges due to their multivesicular structure. Traditionally, open surgery has been considered the safest option in such cases. However, evidence from specialized hepatobiliary centers suggests that laparoscopy can be a feasible alternative even in CE2 cysts, as long as rigorous containment protocols are followed to prevent dissemination [7].

Furthermore, recent studies from high-volume hepatobiliary centers suggest that laparoscopic management of CE2 cysts, when performed with strict protocols, may yield comparable outcomes to open surgery [8, 9].

Intraoperative use of scolicidal solutions (e.g. hypertonic saline, povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine) and protection of the operative field with soaked gauze are essential to prevent peritoneal seeding. Additionally, careful instillation into the cyst cavity, controlled aspiration of contents, and meticulous inspection are critical steps [6, 10].

Recurrence can be minimized with adjunctive therapy with albendazole, initiated 4 days before surgery and continued for 1 to 3 months postoperatively [5]. This multidisciplinary approach, combined with appropriate ultrasound and serologic follow-up, allows for outcomes comparable to open surgery in experienced centers.

To our knowledge, few reports have described laparoscopic treatment of Gharbi II/CE2 cysts after failed PAIR. This highlights the need for further prospective studies and supports laparoscopy as a feasible salvage strategy in selected cases.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Surgical procedure: LLL - GM – CI, Data collection, Case documentation, Literature review: LLL – GM, Draft writing, References, Image curation: LLL – CI, Supervision and critical review of the manuscript: LLL, Writing – original draft: Writing – review & editing: All authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.