-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elise Betz, Kyra Hofmann, Linus Dubs, Peter Šandera, Folco Solimene, Jejunal diverticulosis: complications and management – a case series, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf569, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf569

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Jejunal diverticulosis (JD) is rare (incidence of 0.5%–6%), more common in the elderly, and often asymptomatic. However, complications like diverticulitis, perforation, obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding pose diagnostic and management challenges. This case series describes five patients with complicated JD. Four had jejunal diverticulitis, two with free perforation requiring emergency surgery, two with chronic inflammation. The fifth patient had severe gastrointestinal bleeding undetected by conventional endoscopy requiring advanced diagnostics. Three patients with diverticulitis underwent successful segmental resection, one was managed conservatively. The patient with gastrointestinal bleeding responded to conservative management without a surgical intervention. JD can cause life threatening complications. Clinicians should suspect it in elderly patients with acute abdominal symptoms or obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Prompt imaging and individualized management are crucial for optimizing outcomes. This report highlights the need for greater awareness of JD as a differential diagnosis in abdominal pain and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Introduction

Jejunal diverticulosis (JD) is unlike colon diverticulosis a rare condition with an incidence varying from 0.5%–6% and higher prevalence in the elderly population, predominantly male [1]. These diverticula are typically pseudodiverticula, involving herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscular layer of the intestinal wall [2]. They occur on the mesenteric side of the small bowel and are more frequent in the jejunum than ileum [3, 4]. These patients often present with coexisting diverticula in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract like colon or duodenum [5].

While many individuals with JD remain asymptomatic, ⁓10%–20% may develop complications such as diverticulitis, hemorrhage, obstruction, or perforation [1, 2]. The clinical presentation of jejunal diverticulitis is often nonspecific, with symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and signs of acute abdomen in severe cases [6]. The diagnosis of a hemorrhage caused by JD is equally challenging and is often made after ruling out an upper or lower GI bleeding, which are more common causing hemorrhage [7, 8].

This case series report aims to contribute to the limited body of literature on the complications of JD by detailing the clinical presentation, diagnostic process, and management of five patients with this rare condition.

Case 1

An 82-year-old male patient presented with diffuse lower abdominal pain starting 1 day prior in the emergency department. Clinically, he showed signs of pronounced peritonitis; laboratory tests significantly elevated inflammatory markers. The patient’s medical history included coronary heart disease, hypertension and valvular heart disease with aortic valve replacement via bio prosthesis (TAVI), as well as a chronic kidney disease. There was no previous history of abdominal surgery.

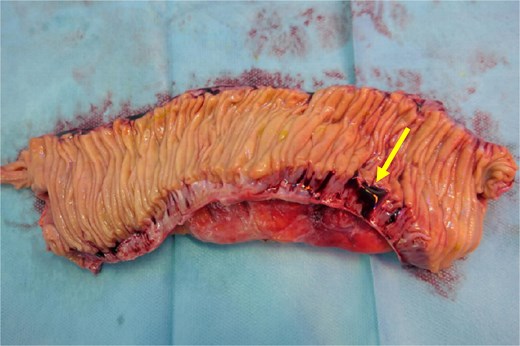

A computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdomen was performed, it showed a long segment of the small bowel with wall thickening in the right lower quadrant, accompanied by a inflammatory change in the mesenteric fat with multiple air bubbles, and free fluid in the pelvis, suggestive of hollow organ perforation (Fig. 1). Given the high suspicion of hollow organ perforation and clinical signs of peritonitis, an indication for exploratory laparotomy was established and performed as an emergency procedure. An antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam was empirically initiated preoperatively.

CTA showing a long segment of small bowel with inflammatory wall thickening and fat stranding of the mesentery with multiple air bubbles.

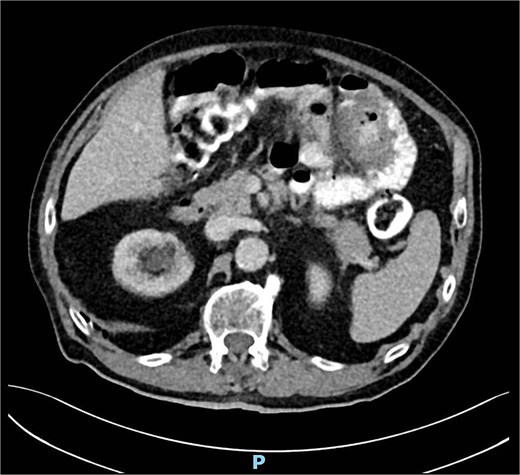

Intraoperatively, a purulent peritonitis was observed, along with an inflammatory, fibrin-covered conglomerate of the small bowel in the lower abdomen. After adhesiolysis, a segment of the distal jejunum ⁓30 cm in length, exhibiting significant inflammatory changes, was identified, with surrounding markedly edematous and thickened mesentery, as well as a diverticulum on the mesenteric wall with suspected perforation into the mesentery. Additionally, multiple non inflamed diverticula, measuring up to 1.5 cm in diameter, were identified along the jejunum. A segmental resection of the inflamed small bowel was performed, followed by a side-to-side anastomosis. The specimen was opened anti-mesenterically in the operating room, allowing for macroscopic verification of the diverticular perforation from an intraluminal perspective (Fig. 2).

Cut open small bowel segment verifying the diverticular perforation (arrow) from an intraluminal perspective.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The antibiotic therapy was discontinued on POD 5, and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on POD 7.

Case 2

An 83-year-old male patient was referred to our emergency department due to elevated inflammatory markers and a minor general deterioration in general despite being treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection. Clinically there was a slight tenderness in his left upper abdomen with a palpable mass. His medical record showed hypertension and chronic kidney disease as for previous surgeries; he underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy 4 months prior as well as an open appendectomy and inguinal hernia repair in his childhood.

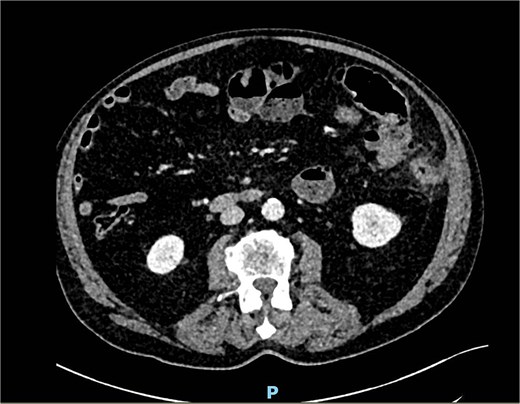

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed an irregularity in the left upper abdomen suspect for a small bowel tumor or inflamed small bowel diverticula (Fig. 3), as well as enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes due to either inflammation or metastasis. Because of the uncertainty of the findings, we decided on an antibiotic treatment and clinical follow up 3 days later.

During the follow up the patient was asymptomatic with no pain or signs of inflammation but still with the palpable mass in the upper left quadrant. In a joint decision-making, we decided on a scheduled small exploratory laparotomy (8 cm incision size) and excision of the tumor to exclude malignancy.

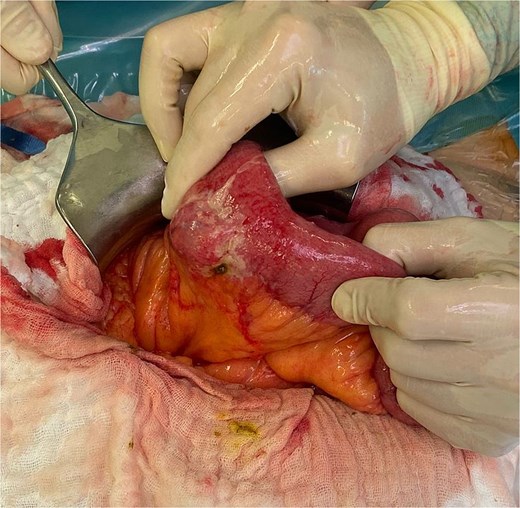

Intraoperatively, a severe JD was observed. The suspicious area describes in the CT scan was a chronic inflammation due to a diverticulum perforation into the mesentery (Fig. 4). We decided on a segmental resection of ⁓50 cm jejunum leaving only one diverticulum near the ligament of Treitz in situ and a side-to-side anastomosis was performed.

Intraoperative finding of JD with a chronic inflammation matching the findings in the CT scan.

The postoperative course was interrupted by a sudden decrease of hemoglobin and hematemesis on the first POD. Further investigation with a CT scan could rule out an active bleeding but showed bloody fluid in stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum. With prophylactic antibiotics, PPI and blood transfusions the patient was quickly stabilized with no further deed for an intervention. After that, the recovery was uneventful, with a prompt return of bowel function and unremarkable wound healing. The patient was discharged on POD 6.

Case 3

An 82-year-old male patient presented with lower abdominal pain and recurrent vomiting as well as fever for a few days. Clinically, the patient showed signs of peritonitis; laboratory tests significantly elevated inflammatory markers. His medical record showed hypertension and a known diverticulosis of the colon and small bowel. There was no history of previous surgeries.

A CT scan of the abdomen showed an inflammation in the lower left abdomen due to either a colon diverticulitis or small bowel diverticulitis, some free fluid and little air bubble indicating for a hollow organ perforation (Fig. 5). Given all those findings, we decided to go for a diagnostic laparoscopy. An empiric antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone/metronidazole was initiated.

CT scan showing signs of inflammation and free air in the left abdomen.

Intraoperatively, a general peritonitis was detected with intestinal contents present. The jejunum showed signs of inflammation and some adhesions to the transverse and ascending colon making a safe laparoscopic continuation impossible. Therefore, a laparotomy was performed with adhesiolysis and resection of 40 cm jejunum including the perforated diverticulum (Fig. 6) as well as other inflamed diverticula, leaving only one not inflamed diverticulum near to the ligament of Treitz. For reconstruction a side-to-side anastomosis was done and an intraabdominal drain was placed.

Postoperative the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for cardiovascular support with catecholamines due to a septic shock. Because of the severe peritonitis the antibiotic treatment was changed to piperacillin/tazobactam. On POD 4 the patient was transferred to the surgical ward with an uneventful postoperative course. The antibiotic therapy was discontinued on POD 5, and the patient was discharged on POD 8.

Case 4

A 77-year-old male patient presented with an obstipation for 5 days and massive abdominal pain as well as inappetence. Clinically he presented with a localized peritonitis in the lower abdomen and fever, laboratory tests showed elevated inflammatory markers. The medical history showed a known coronary heart disease, tachy-brady-syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

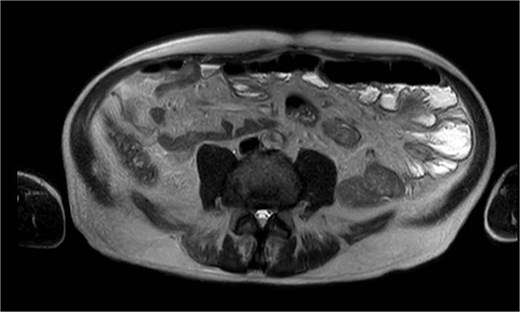

A performed CT scan showed a suspicious process in the left hemiabdomen with the involvement of the small bowel and its mesentery (Fig. 7), as well as enlarged lymph nodes. Therefore a radiological suspicion of malignancy was postulated. Adding to that a mechanical small bowel obstruction was seen in the CT scan due to the described mass.

An antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam was empirically initiated as well as a conservative therapy of small bowel obstruction with oral intake of Telebrix®. We also scheduled further investigations ruling out a malignancy. The performed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen then showed a jejunal diverticulitis (Fig. 8). During the hospital stay we observed a significant decrease of the inflammatory markers, a return of bowel movement with established stool passing as well as a pain-free patient. The antibiotic therapy was discontinued on the day of dismissal, on day 7.

MRI showing multiple jejunal diverticula on the mesenteric side.

Case 5

An 81-year-old male patient presented with a gastrointestinal bleeding in the emergency department. He reported about an ongoing gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding for 3 days in form of terry stool. Clinically his vital signs were stable with a known tachyarrhythmia due to atrial fibrillation. His medical history also showed a coronary heart disease and hypertension, as well as his long-term medication being Rivaroxaban as oral anticoagulation medication alongside antihypertension medication. The laboratory tests reviled severe anemia (Hb 5.2 g/dl).

Because of severe hemorrhage, we decided on a clinical monitoring at the ICU despite any instability. A conservative management was applied: the patient received tranexamic acid, PPI and in total transfusions of five red blood cell concentrates as well as two fresh frozen plasma concentrates. The performed endoscopies, colonoscopy as well as gastroscopy showed no active bleeding. Findings of an esophagitis as well as a colon diverticulosis were not helpful in identification of the bleeding source. After 24 h of uneventful monitoring the patient was transferred to the surgical ward. He remained stable with an Hb of 8.4 g/dl for 2 days.

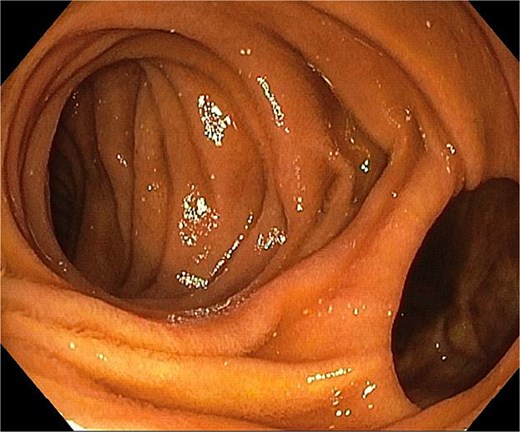

A new drop of the hemoglobin (6.3 g/dl) led to a CTA and transfusion of two more red blood cell concentrates. The CT scan showed a venous seepage in the small bowel, presumably the jejunum (Fig. 9). In a re-do gastroscopy we saw a JD (Fig. 10), but the origin of the bleeding could not be detected as only 20–30 cm jejunum could be reached. The following single-balloon enteroscopy until 2 m post the pylorus showed a pronounced jejunual diverticolisis with the largest diverticula located ⁓50 cm post the pylorus. In this region, there were also prominent blood vessels inside the diverticula detected, but without signs of an ongoing bleeding. Therefore no further intervention was done.

The remaining hospital stay was uneventful. The oral anticoagulation medication was resumed but changed to Apixaban before the dismissal on day 9, due to less GI bleeding complications in comparison with rivaroxaban.

Discussion

JD is a rare condition, often asymptomatic, but it can lead to severe complications such as diverticulitis, perforation, obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding [4]. Unlike colonic diverticulosis, which is well documented and widely studied, JD remains underreported due to its nonspecific presentation and the challenges associated with diagnosis. There are no guidelines to help with the management.

JD often presents with nonspecific symptoms, posing a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. In this report, we have described the clinical courses and management of five patients diagnosed with complications of JD, highlighting the diversity of its presentation, management possibility and outcome. Two patients presented with free perforation, a life-threatening complication that necessitated urgent surgical intervention, while the other two experienced chronic inflammation with one requiring elective surgery to exclude malignancy and one managed conservative. Three out of the four patients with diverticulitis were successfully treated with segmental resection of the affected portion of the jejunum, underscoring the role of surgery in managing both acute and chronic complications of this condition [9].

Jejunal diverticular bleeding, as seen in the fifth patient, poses a diagnostic challenge. Unlike diverticulitis, which often presents with localized symptoms, bleeding may be intermittent and self-limited or massive and life threatening. Standard endoscopy is limited due to the small bowel's anatomy and CTA or single-balloon enteroscopy may be required for localization. Conservative management is often successful, but in case of recurrent or severe and life-threatening hemorrhage, surgical intervention may be necessary [5, 10].

Conclusion

JD remains a rare but clinically significant entity with potentially severe complications.

These cases emphasize the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for complications of JD in patients presenting with acute or chronic abdominal symptoms as well as gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly in the presence of risk factors such as advanced age or a history of diverticulosis, bleeding or oral anticoagulation. Prompt diagnosis through imaging and early intervention in complicated cases are critical to optimizing outcomes. Our findings add to the growing body of evidence that JD, though rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and managed with a tailored approach based on the severity of the disease. As for patients with a gastrointestinal bleeding, which show no sign of the more common upper or lower GI bleeding in standard endoscopy, a bleeding caused by JD has to be considered.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported.