-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdel Kémal Bori Bata, Désiré Nékoua, Ahmad Ibrahim, Arnaud Sonou, Léopold Codjo, Pierre Demondion, Surgical management of chronic type A aortic dissection in sub-Saharan Africa: a five-case series from a Beninese center, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf513, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf513

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Stanford type A aortic dissection is a condition associated with high mortality in the absence of prompt surgical management. In sub-Saharan Africa, both the diagnosis and management of the acute phase remain particularly challenging. Consequently, the few patients who survive the acute phase are often diagnosed during the chronic stage. We present a series of five cases of chronic type A aortic dissection surgically managed in Benin.

Introduction

According to the Stanford classification, type A aortic dissection is an acute, life-threatening emergency requiring urgent surgical repair. Global data suggest that approximately 40% of patients die before reaching the hospital, with in-hospital mortality increasing by 1% per hour after admission and a perioperative mortality rate ranging between 5% and 20% [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, limited access to advanced cardiovascular care and imaging modalities results in delayed diagnosis and intervention [2]. This diagnostic delay contributes to the significant rise in morbidity and mortality related to aortic diseases—with an estimated 155.5% increase from 1990 to 2019 in low- and middle-income regions [3]. Consequently, the small proportion of patients who survive the acute phase progress to the chronic form of dissection. Chronic type A aortic dissection (CTAAD) is defined as a persisting dissection beyond 90 days [4]. In this report, we present five cases of CTAAD managed with surgery in Benin.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective descriptive case series conducted at our hospital in Benin. Patients with chronic Stanford type A aortic dissection, who underwent surgical treatment between March 2021 and January 2025 were included. The diagnosis was established by transesophageal echocardiography and confirmed in all cases by thoracic CT angiography. Postoperative follow-up was conducted by the surgical team at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery.

Results

Case 1

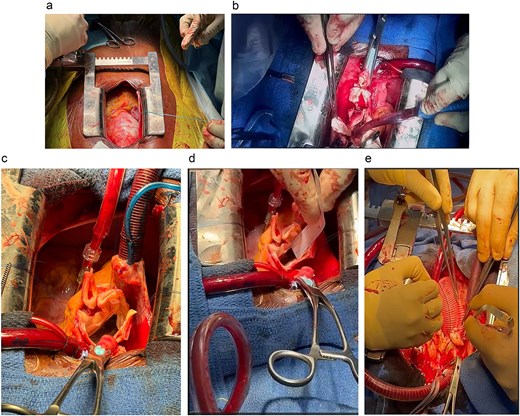

A 33-year-old man with a history of Marfan syndrome and former tobacco use presented with three months of recurrent chest pain. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed an aneurysmal ascending aorta with an anteroposterior diameter of 67 mm, a dissection extending to the descending aorta, and grade III aortic regurgitation. Thoracic CT angiography (angioCT) confirmed a dissection of the ascending aorta and a fusiform dilation of 67 mm limited to this segment (Fig. 1). A median sternotomy was performed, followed by aortic and atriocaval cannulation. Intraoperatively, the intimal flap was identified 2 cm above the sinotubular junction on the anterolateral side of the ascending aorta, extending to the descending aorta. The patient underwent a modified valve-sparing aortic root replacement (Tyrone David procedure) following the El Arid–Modine technique (Fig. 2a–e). Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and aortic cross-clamp times were 166 and 143 minutes, respectively. Postoperative TEE showed minimal aortic regurgitation. Recovery was uneventful, and no complications were observed over six months of follow-up.

Coronal CT angiography showing a chronic dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta.

Modified Tyrone David procedure using the El Arid–Modine technique. (a) Intraoperative view showing dilatation of the aortic root, confirming the preoperative diagnosis and justifying the indication for the Tyrone David valve-sparing technique. (b) Excision of the Valsalva sinuses: Resection of diseased aortic tissue while preserving the valve commissures and isolating the right and left coronary ostia. (c) Suspension of the aortic valve commissures prior to measuring commissural heights. (d) Measurement of commissural height to determine the appropriate size of the Dacron graft (30 mm). (e) Reimplantation of the coronary arteries into the vascular graft following implantation.

Case 2

The second patient, a 51-year-old woman with no known cardiovascular history, consulted for one year of chronic chest pain. TEE detected an aneurysmal dissection confined to the ascending aorta, measuring 91 mm, and moderate aortic regurgitation. Thoracic angioCT revealed a type A aneurysmal dissection extending to the aortic arch, with the ascending aorta measuring 106 mm. Surgery was performed via a median sternotomy. The right atrium was cannulated with a dual-stage atriocaval cannula, and arterial inflow was established via the brachiocephalic trunk. Intraoperative evaluation revealed a type A dissection extending to the arch, with a supracoronary entry tear. Under hypothermia at 20°C and circulatory arrest with cerebral protection (37 minutes), a supracoronary ascending aortic graft was implanted, and the hemiarch was replaced using a Dacron prosthesis. CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were 131 and 95 minutes, respectively. Postoperative TEE showed minimal aortic regurgitation. The patient remained complication-free over one year of postoperative follow-up.

Case 3

A 29-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension and a previous hemorrhagic stroke one year prior presented with chest pain that began three months earlier. TEE revealed an aneurysmal ascending aorta (56 mm) with an intimal flap, severe aortic regurgitation, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and grade II mitral regurgitation. The CT angiography confirmed a Stanford type A aortic dissection, associated with an aneurysmal ascending aorta (55 mm) and the presence of an intimal flap at the sinotubular junction. A median sternotomy was performed, and CPB was established via aortic and atriocaval cannulation. Surgery involved mechanical aortic valve replacement, implantation of a supracoronary ascending aortic graft, and tricuspid annuloplasty with a No. 30 Sovering ring. CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were 129 and 93 minutes, respectively. The patient developed immediate postoperative hemorrhagic shock but was managed successfully without surgical re-exploration. No additional complications were recorded over one year of follow-up.

Case 4

A 51-year-old hypertensive man presented with NYHA class IV dyspnea and recurrent episodes of cardiac decompensation. TEE showed a dissection confined to the sinotubular junction, a 72 mm dilation of the tubular ascending aorta, and a normal aortic root (38–40 mm) with central massive aortic regurgitation. Thoracic angioCT showed a dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta, extending to the left common carotid artery. A median sternotomy was performed, with cannulation of the brachiocephalic trunk and right atrium. Intraoperative evaluation revealed a type A dissection reaching the root of the brachiocephalic trunk, with a supracoronary entry tear. The patient was cooled to 18°C under circulatory arrest and received 32 minutes of antegrade cerebral perfusion. A composite aortic root replacement (Bentall procedure) with a mechanical valved conduit was performed. CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were 160 and 127 minutes, respectively. Postoperative TEE showed a normally functioning aortic prosthesis with minimal paravalvular leak. Complications included a lacunar ischemic stroke, and a left pleural effusion requiring drainage. No additional complications arose during one year of follow-up.

Case 5

A 43-year-old man was referred for management of multiple valvular lesions (mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation) likely of rheumatic origin. Preoperative TEE detected a dilated aorta (72 mm at the sinotubular junction, 54 mm at the sinuses) with an intimal flap originating at the root, forming an anteroright false lumen. Severe central aortic regurgitation was present alongside significant tricuspid regurgitation and minimal mitral regurgitation (grade 1). AngioCT confirmed a Stanford type A dissection extending to 2 cm beyond the renal artery. A median sternotomy was performed with cannulation of the brachiocephalic trunk and the right atrium (atriocaval cannulation). Under hypothermia at 36°C, with 1 minute and 30 seconds of circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral protection, the patient underwent a composite aortic root replacement (Bentall procedure) with a mechanical valved conduit and a tricuspid annuloplasty using a Sovering Band No. 30. CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were 127 and 90 minutes, respectively. Postoperative TEE showed a properly functioning prosthetic valve with no paravalvular leak, minimal-to-moderate mitral regurgitation, and a nonstenotic tricuspid repair. The patient developed complete atrioventricular block requiring permanent pacemaker implantation. No other incidents occurred during 6 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Our series demonstrated a male predominance (four men and one woman), consistent with multiple previous studies [5, 6]. Patient ages ranged from 29 to 51 years, with a mean of 41.4 years—lower than the 61 to 62.1 years reported in the literature [5, 7]. This finding underscores the substantial burden of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among younger adults.

Chest pain was reported in four of the five patients, making it the most frequent presenting symptom. Several authors have reported a high prevalence of asymptomatic presentation among patients with CTAAD, with chest pain documented in only 20% to 31.7% of cases. This subgroup frequently included individuals with a history of prior cardiac surgery [5, 7]. The absence of asymptomatic presentations in our series may be attributed to the fact that none of the patients had previously undergone cardiac surgery.

All patients in our series had an aortic diameter exceeding 55 mm (range: 56–106 mm), corroborating Rylski et al., who observed that patients with chronic dissections have significantly larger ascending aortic diameters than those with acute dissections, with a reported mean diameter of 6.0 cm [5].

Surgical repair remains the gold standard for managing CTAAD, with indications including severe aortic regurgitation, progressive aortic dilatation, or symptom onset [8]. No deaths occurred within one year of follow-up. Postoperative complications consisted primarily of pulmonary complication (1/5), stroke (1/5), and third-degree atrioventricular block (1/5). These findings are consistent with the literature, which reports favourable postoperative outcomes and mortality ranging from 1% to 15% after open repair [8]. These results highlight the effectiveness of surgical intervention and underscore the need for improved diagnostic and therapeutic resources. Outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for CTAAD associated with aneurysm are varied and primarily indicated for high-risk patients, with 5-year survival rates estimated at 82.31% and reintervention required in 8.38% of cases [9, 10]. Series of patients with CTAAD managed exclusively medically have demonstrated poor outcomes, with estimated 1-year mortality approaching 60% [7, 8].

Conclusion

This five-case series confirms that complex surgical management of chronic Stanford type A aortic dissection is feasible in sub-Saharan Africa with encouraging early outcomes. It underscores the need to strengthen diagnostic capacities, develop regional surgical centres of excellence, and establish outcome registries to guide timely intervention and reduce aortic mortality in resource-limited settings.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case series involved surgical procedures performed as part of standard clinical care. Formal ethics committee approval was not required for the retrospective analysis and reporting of these cases, in accordance with the institutional policies. However, written informed consent to participate and to use anonymized clinical data was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of these case reports and accompanying images.