-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liman Zhang, Jie Yang, Qiang Wang, Hao Jiao, Lili Wang, Lifang Wang, Meizhen Liu, Secondary rectal perforation following procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf501, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf501

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) is designed to reposition displaced anal cushions by circumferential resection of the distal rectal mucosa. PPH offers advantages over traditional excisional hemorrhoidectomy, including less postoperative pain and a shorter hospital stay. However, complications such as anastomotic dehiscence and rectal perforation may occur and require prompt management. This case report presents a patient who developed rectal perforation following PPH, aiming to provide valuable insights for clinical practice.

Introduction

The procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) involves circumferential resection of submucosal tissue above the dentate line using a circular stapler [1]. First introduced by Antonio Longo in 1998 [2], PPH is primarily indicated for Grades III and IV hemorrhoidal prolapse. Despite its advantages over traditional methods, such as reduced intraoperative bleeding, decreased postoperative pain, faster recovery, and shorter hospitalization [3], complications like postoperative pain, hemorrhage, stenosis, rectovaginal fistula, rectal perforation, and chronic anal discomfort, have been reported [4]. This case report details a patient who developed rectal perforation following PPH, highlighting the importance of recognizing and managing such complications.

Case report

A 34-year-old male presented with a 1-month history of anal mass protrusion and post-defecatory bleeding. He had no significant medical history, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or cardiovascular disorders. After admission, the patient was evaluated by specialized examination and diagnosed with Grade III internal hemorrhoids. Routine laboratory tests and preoperative abdominal radiography showed no abnormalities. After excluding surgical contraindications, the patient underwent PPH under spinal anesthesia.

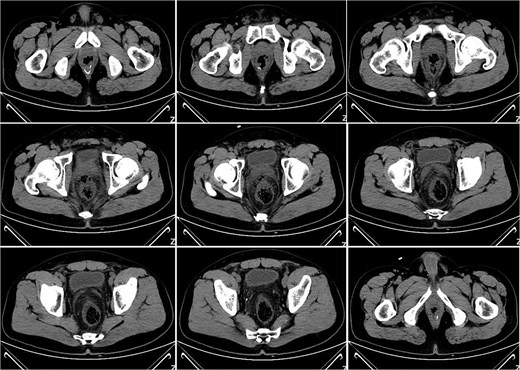

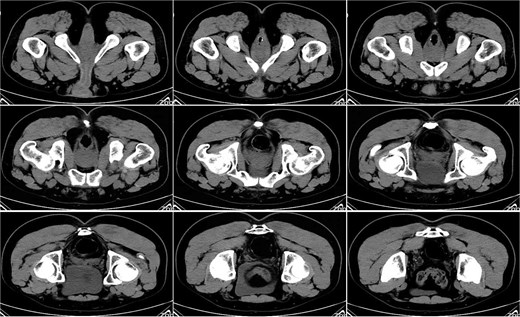

On postoperative Day 7, the patient developed a fever (38.5°C) and mild lower abdominal discomfort. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 16.06 × 109/l, neutrophil percentage: 89.1%). A pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan suggested cystitis (Fig. 1). Anti-infective therapy with intravenous cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium was initiated. The patient’s vital signs, complete blood count, and temperature were closely monitored.

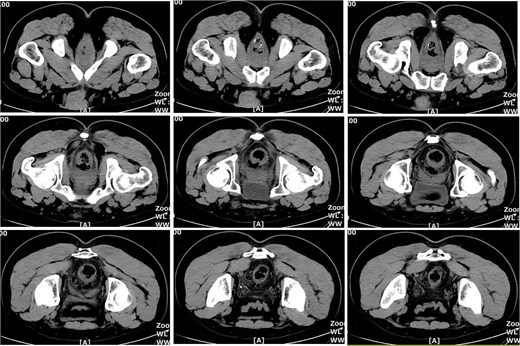

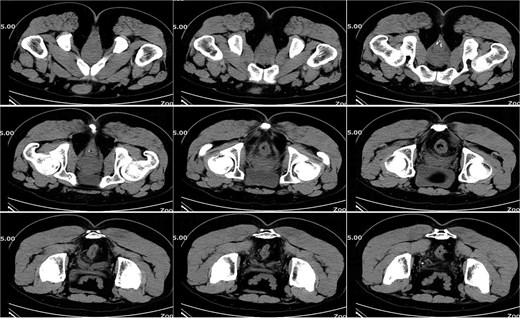

On postoperative Day 10, a repeat complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 9.74 × 109/l and a neutrophil percentage of 69.5%. The patient’s temperature ranged between 36.4 and 37.4°C, and abdominal discomfort was partially alleviated. A follow-up pelvic CT scan revealed a breach in the anterior rectal wall with gas density shadows communicating with the surrounding area, accompanied by filamentous exudate density shadows and multiple gas density shadows (Fig. 2). These findings indicated rectal wall edema and anterior wall perforation with surrounding infection. Anorectal examination revealed a 0.5 × 0.5 cm ulcerative lesion at the 5 o’clock position of the anastomosis site in the knee–chest position. This was considered rectal perforation secondary to anastomotic dehiscence. Given the absence of peritoneal irritation signs and normalization of the white blood cell count, a conservative treatment plan was adopted after discussion with the patient. This plan involved continuing anti-infective treatment with intravenous cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium.

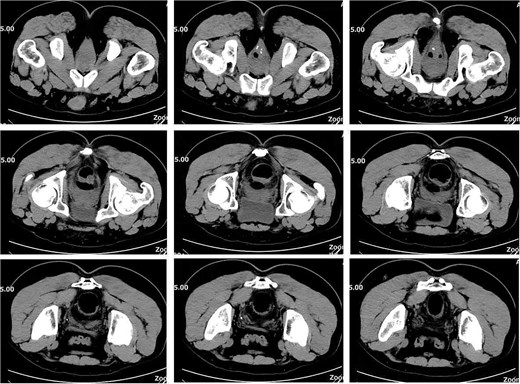

On postoperative Day 15, a complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 9.12 × 109/l and a neutrophil percentage of 77.5%. Pelvic CT demonstrated rectal wall edema, anterior wall perforation, and partial absorption of the surrounding infection, indicating reduced infection severity compared to the previous scan on postoperative Day 10 (Fig. 3). Given the patient’s satisfactory response to antibiotic therapy and absence of ongoing infection signs, intravenous antibiotic treatment was discontinued.

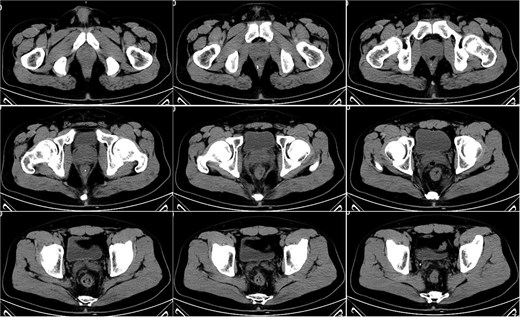

On postoperative Day 21, a follow-up pelvic CT scan indicated local gas accumulation around the rectum, suggesting an absorption phase of the infection (Fig. 4). By postoperative Day 28, a pelvic CT scan demonstrated minor gas accumulation at the anterior edge of the rectosigmoid junction, consistent with infection resolution and gas absorption in the surrounding area (Fig. 5). By postoperative Day 49, a pelvic CT scan revealed no abnormal density shadows in the perianal skin and soft tissues, with preserved fat planes (Fig. 6), indicating complete resolution of the perirectal infection and restoration of normal clinical status.

Discussion

In this case, preoperative examination confirmed third-degree prolapsed hemorrhoids, aligning with the indications for PPH surgery. On postoperative Day 7, the patient developed symptoms of infection, including lower abdominal pain, fever, and elevated white blood cell count. The initial pelvic CT scan suggested cystitis, but a follow-up scan on postoperative Day 10 revealed rectal perforation. This likely resulted from delayed anastomotic dehiscence, which was initially too small to be detected on the first CT scan. Subsequent activities such as bowel movements may have enlarged the perforation, leading to symptoms of intestinal perforation.

Causes of anastomotic leaks after PPH surgery include stapler malfunction or misoperation [5], excessive stapler insertion depth [6], inadequate bowel preparation causing local infection, overly deep placement of the purse-string suture reaching the muscular layer and causing full-thickness bowel wall injury, excessive mucosal resection led to high anastomotic tension, traction on the anastomosis when withdrawing the stapler, and surgeon inexperience [7, 8]. In cases of rectal perforation detected intraoperatively with adequately prepared bowel, direct transanal repair is feasible. If peritonitis occurs, prompt repair, decontamination, thorough drainage, and fecal diversion when necessary are essential. Key treatments include sigmoid loop colostomy, rectal posterior space drainage, and anastomotic repair. For infections below the peritoneal reflection due to anastomotic dehiscence, transrectal anal drainage is effective. Severe intra-abdominal bleeding and rectal perforation post-PPH have been successfully managed with transanal drainage [9]. In this case, the patient’s infection was localized without peritonitis, so conservative treatment was sufficient to control the inflammation.

PPH has been widely used globally for over two decades. PPH has been widely used globally for over two decades. However, with its extensive application, many severe complications such as intestinal perforation, pelvic infection, and rectovaginal fistula have been reported, prompting a reevaluation of its indications and application. In 2020, the European Society of Coloproctology lowered the evidence level for stapler rectal resection in their hemorrhoid treatment guidelines. While PPH is significant in hemorrhoid surgery history, a more objective assessment of its indications, clinical efficacy, and complications is crucial to balance its benefits and risks.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.