-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdullah Alruways, Nader Alharbi, Turki Alharbi, Faisal Alotaibi, Ahmed Aloraini, Nawaf Alharbi, Azygos lobe mimicking pneumothorax in trauma: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf350, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf350

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a 20-year-old male involved in a high-energy vehicle accident with back pain, chest pain, and a scalp abrasion. A supine chest radiograph revealed a linear lucency in the right apical lobe, raising concern for pneumothorax or a retained foreign body. A contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) identified an azygos lobe with its characteristic fissure and preserved pulmonary markings, with no evidence of pneumothorax or foreign objects. The patient remained stable and was discharged without intervention. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges of recognizing congenital anomalies like the azygos lobe, present in 0.4%–1.2% of the population, which can mimic critical conditions such as pneumothorax or foreign bodies, particularly in trauma settings. Identifying key imaging features, including the azygos fissure’s alignment and normal lung markings, is essential to avoiding misdiagnosis. CT is the gold standard for resolving uncertainty, ensuring accurate diagnosis, and preventing unnecessary interventions in trauma cases.

Introduction

Chest radiography (CXR) is an essential part of initial trauma assessment because it can rapidly detect life-threatening abnormalities such as pneumothorax [1]. However, because anatomical changes can mimic clinical results, it is challenging to evaluate, particularly when under severe load [2, 3]. The azygos lobe, though a recognized anatomical variant, is frequently overlooked in clinical practice due to its asymptomatic nature and its potential to be mistaken for other pathologies on imaging, a congenital abnormality that affects 0.4%–1.2% of the population [3].

A fissure made up of four pleural layers is created when the azygos vein abnormally migrates through the right upper lung, forming the azygos lobe [4]. This fissure can mimic the visceral pleural line of a pneumothorax on CXR, showing up as a thin, curvilinear opacity [5].

There are few case reports illustrating azygos lobe misinterpretation as pneumothorax in trauma, despite the fact that it is acknowledged in radiological literature [6]. Given that supine CXR, the norm in trauma bays, increases diagnostic uncertainty because of technical constraints, this disparity emphasizes the necessity for increased knowledge among emergency and trauma teams [7]. Computed tomography (CT) is still the gold standard for advanced imaging when it comes to elucidating unclear findings, but its selective application depends on clinical-radiological connection [3].

We describe a case in which an azygos lobe in a trauma patient who was hemodynamically stable mimicked pneumothorax, highlighting the significance of identifying anatomic variations in such cases.

Case presentation

A male patient, aged 20, arrived at the emergency room following a high-mechanism road traffic accident. His main symptoms were abrasion on his scalp, back ache, and chest pain. The patient denied focal neurologic abnormalities, syncope, or dyspnea.

He was alert, oriented to time, place, and person, and hemodynamically stable during the primary survey (heart rate: 88 bpm, blood pressure: 163/98 mmHg, SpO₂: 98% on room air). His score on the Glasgow Coma Scale was 15/15. A second examination revealed an abrasion on the right parietal scalp and tenderness along the mid-thoracic spine. When the chest was auscultated, there were no crackles or wheezing sounds, and the breath sounds were equal on both sides. Hemothorax, pneumothorax, pelvic hemorrhage, free intra-abdominal fluid, and pericardial effusion were not detected by the extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma test.

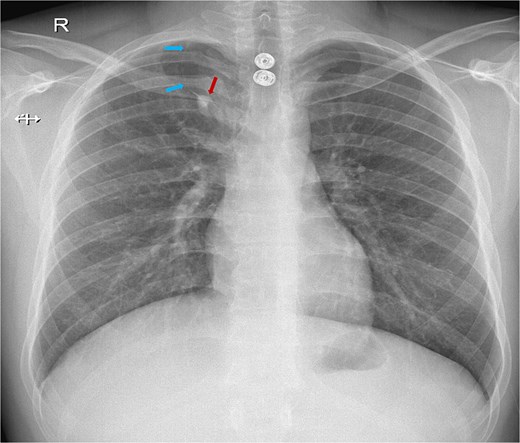

As part of the trauma protocol, a supine chest X-ray (CXR) was obtained. The trauma team suspected a pneumothorax based on the imaging showing a longitudinal lucency along the right apical area (Fig. 1). A minor right apical pneumothorax or, less commonly, a radiopaque foreign body artifact was initially suspected during radiographic assessment. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest was promptly acquired due to the high-risk mechanism and the possibility of concealed thoracic injury.

Chest X-ray showing a white line crossing from the lateral to the medial side of the right upper lung. The blue arrows indicate the azygos fissure, while the red arrow points to the azygos vein located at the base of the fissure with the characteristic ``tear drop'' sign.

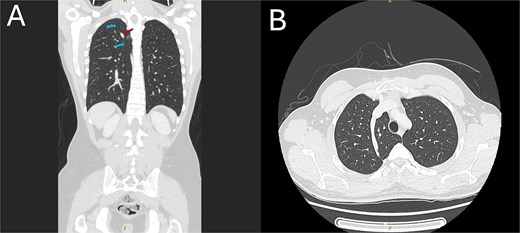

The CT scan revealed an azygos lobe in the right upper lung, definitively ruling out pneumothorax. The azygos vein was situated at the inferior edge of the curvilinear azygos fissure, which extended toward the right tracheobronchial angle (Fig. 2). With preserved lung markings within the lobe, ruling out pneumothorax, a retrospective study of the CXR verified that the lucency matched the azygos fissure.

CT chest demonstrating the azygos lobe. (A) Coronal view with blue arrows indicating the azygos fissure and the red arrow pointing to the azygos vein. (B) Axial view shows the azygos fissure is seen as a curved, sharply marginated line in the right upper lobe, typically situated anteromedially.

Since there was no clinical or radiographic indication of pneumothorax, the thoracic surgery team postponed invasive procedures. After being monitored for 24 h, the patient was released with conservative treatment for musculoskeletal pain.

Discussion

This particular case underscores a significant challenge in trauma imaging: distinguishing between actual conditions such as pneumothorax and anatomical variations like the azygos lobe. Although the azygos lobe is a harmless and incidental finding, its appearance on supine trauma chest X-rays can resemble the visceral pleural line of a pneumothorax because of technical limitations that obscure anatomical details [7, 8].

The azygos vein invaginates across the right upper lung during embryonic development, forming the azygos fissure, a four-layered pleural reflection that gives rise to the azygos lobe. This fissure has a distinctive inferomedial trajectory toward the right tracheobronchial angle and manifests as a thin, curvilinear opacity on CXR [3, 4]. This feature was first misidentified as a pneumothorax in our patient (Fig. 1). Previous investigations have reported similar diagnostic errors, where the appearance of the azygos lobe has been misinterpreted as other pulmonary conditions [3].

The initial misdiagnosis was probably influenced by two main factors:

(1) Bias in trauma context: The high-energy character of the damage resulted in misinterpretation of insufficient or unclear evidence, inciting fears of possibly fatal conditions.

(2) Insufficient recognition of anatomic variants: Despite the azygos lobe occurring in ⁓1% of the population, it is hardly detected in trauma imaging techniques [3].

CXRs commonly utilized in trauma scenarios, possess inherent limitations in their capacity to delineate intricate anatomical details.

To address these diagnostic challenges, sophisticated imaging techniques such as contrast-enhanced CT are essential. CT confirmed the presence of an azygos lobe by displaying lung tissue inside it and the azygos vein across the fissure, therefore firmly excluding pneumothorax [3]. The American College of Radiology highlights the crucial role of CT in precisely detecting thoracic injuries [9].

The presence of an azygos lobe in trauma patients adds complexity to the diagnostic process, especially in cases where pneumothorax may be a concern. The azygos lobe, while not commonly associated with spontaneous pneumothorax, can obscure standard imaging indicators, leading to difficulties in diagnosis [10, 11]. Some studies suggest that the azygos lobe may offer a protective mechanism against spontaneous pneumothorax; however, this protective role does not extend to traumatic pneumothorax [11]. High-energy trauma mechanisms often result in concealed pneumothorax that may not be readily apparent on initial imaging, thus complicating the diagnostic process even more [12].

Guidelines from organizations such as the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) emphasize the importance of comprehensive imaging and a team-based approach in handling thoracic injuries to reduce diagnostic errors and improve patient results [13]. The combination of advanced imaging techniques and the collaboration among trauma experts, radiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons was essential for achieving an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, identifying an azygos lobe in trauma patients requires a high index of suspicion for pneumothorax and other thoracic injuries. This case highlights the importance of advanced imaging techniques, particularly CT, in providing definitive diagnoses. A multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with complex thoracic injuries, ensuring accurate diagnosis, and facilitating effective management.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this publication.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. No identifying information has been included to maintain the patient’s anonymity.