-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael John Furey, Mary Elizabeth DeHaven, Mohammed Amer Swid, Richard Aaron Lopez, Appendiceal diverticulitis masked as acute appendicitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf315, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf315

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Diverticula of the appendix have been the subject of study since the early 1900s. Appendiceal diverticulitis has varying presentations that can be acute or chronic and has features that differentiate it from classical acute appendicitis. We present the case of a 61-year-old female who was incidentally found to have appendiceal diverticulitis. Appendiceal diverticula are divided into two types, congenital and acquired. This patient developed an acquired appendiceal diverticula. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of acquired appendiceal diverticulosis is unknown. Risk factors associated with acquired appendiceal diverticulosis include male gender, older adults (>30 years old), Hirschsprung’s disease, and cystic fibrosis. They were not found to be associated with colonic diverticulosis. Of these known risk factors, our patient only met the criteria of being an older adult. With the post-operative diagnosis of appendiceal diverticulitis, the patient does not require any further intervention beyond the appendectomy which was already completed.

Introduction

The findings of diverticula of the appendix have been the subject of study since the early 1900s, described as “evaginations,” “protrusions,” or “herniations” of the mucosa, muscularis mucosa, and submucosa through defects in the muscular layer of the appendix [1]. Dr. Stout completed the first study of its kind, examining and characterizing seven appendixes with diverticula, six post-operative specimens and one postmortem specimen obtained on autopsy [1]. Appendiceal diverticulitis not only has varying presentations that can be acute or chronic but also has features that differentiate its presentation from classical acute appendicitis [2–4]. Unlike typical acute appendicitis, appendiceal diverticulitis presents in older age groups (>30 years old), patients have a history of previous attacks of abdominal pain, and there is an absence of additional gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, anorexia, or vomiting [2–4].

Case report

We present the case of a 61-year-old female who was evaluated in the emergency department for 1-day history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain not associated with nausea, emesis, anorexia, fevers, or chills. Her medical and surgical history are significant for the following: coronary artery disease with previous myocardial infarction, currently on aspirin and Plavix, status-post stenting in 2018 and 2021; hypertension; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; diverticulitis, status-post previous Hartman’s procedure with subsequent end-colostomy reversal; Barrett’s esophagus; hypothyroidism; psoriasis; hyperlipidemia; and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Of note, she reported her abdominal pain present during this emergency department visit was similar to a previous episode of diagnosed acute appendicitis, ~5 months prior that was managed non-operatively with a course of antibiotics. At this time, work-up in the emergency department showed a white blood cell count of 9.66 (without a left shift), and a 1.2-cm appendix without an appendicolith, with surrounding soft tissue stranding and a small amount of free fluid was seen on computed tomography (CT) scan. She was admitted to the acute care surgery service and consented for laparoscopic appendectomy. Preoperative diagnosis of diverticulum of the appendix is difficult and rarely occurs [3, 4]. While CT, ultrasound, and barium enemas have previously diagnosed appendiceal diverticulosis, many cases of appendiceal diverticulitis appear similar on imaging to acute appendicitis [2, 3].

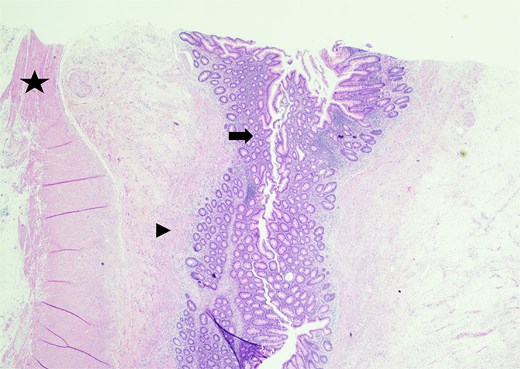

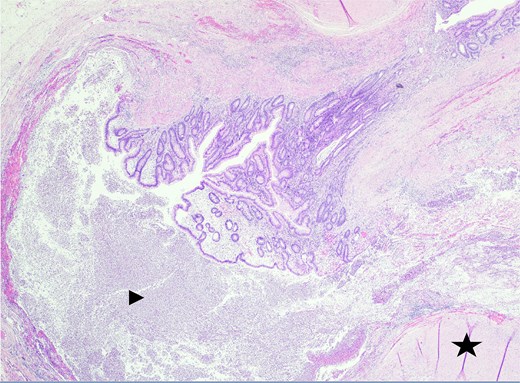

In the operating room, multiple adhesions from the patient’s prior colostomy site and colon resection were noted. The appendix was found to be dilated, acutely inflamed, and hyperemic, consistent with the suspected diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Adhesions from the appendix to the abdominal sidewall were dissected bluntly, pulling the appendix to a more medial position. The harmonic surgical device was used to divide the appendix mesentery and the gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler with a blue load was used to divide the appendix from the base of the cecum. Final pathology showed an intact vermiform appendix measuring 6.5 × 1.5 cm with 3.2 × 2.5 × 1.6 cm portion of the attached mesoappendix. On gross examination, tan-pink hemorrhagic serosa with minimal adhesions and no exudate was noted. Sectioning of the specimen revealed a 0.5-cm in diameter lumen filled with a moderate amount of hemorrhagic purulent fecal material and at the distal tip, an intact diverticulum with wall measurement up to 0.2 cm in average thickness (Figs 1 and 2).

Sectioning of the intact vermiform appendix, top portion, showing the muscularis propria (star), muscularis mucosa (arrowhead), and colonic mucosa (arrow).

Sectioning of the intact vermiform appendix, bottom portion, with the appendiceal diverticula showing the muscularis propria (star) and acute inflammatory cells, neutrophils (arrowhead), within.

Discussion

Appendiceal diverticula are divided into two types, congenital and acquired [1–4]. The majority are acquired with an incidence between 0.004% and 2.1% from appendectomy studies and 0.20% and 0.66% from autopsy studies [1, 2]. Acquired diverticula are more common and most are found in the distal one third of the appendix (60%). There are usually multiple diverticula, however, a single diverticulum can be seen, and diverticula are typically smaller, 2–5 mm [1–3]. Congenital diverticulosis of the appendix is rarer, typically singular, and is mostly found along the anti-mesenteric border of the appendix [2]. Histologically, congenital diverticula are true diverticula as they contain all layers of the wall of the appendix (mucosa, submucosa, serosa, and muscle layer), where acquired diverticula are false or pseudodiverticula, as the wall only contains the mucosa, submucosa, and serosa (not the muscle layer) [1–3].

Reviewing our patient’s specimen, it was likely they developed an acquired appendiceal diverticula. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of acquired appendiceal diverticulosis is unknown [2]. Risk factors associated with acquired appendiceal diverticulosis include male gender, older adults (>30 years old), Hirschsprung’s disease, and cystic fibrosis, and they were not found to be associated with colonic diverticulosis [2]. Of these known risk factors, our patient only met the criteria of being an older adult.

Our patient was discharged from the hospital on post-operative Day 0. No further information regarding their post-operative course is available as the patient did not keep their post-operative follow-up appointment. With the post-operative diagnosis of appendiceal diverticulitis, the patient does not require any further intervention beyond the appendectomy which was already completed [4]. However, in patients where an uninflamed appendix containing diverticula is diagnosed intraoperatively, incidental appendectomy is recommended [4]. This is because the incidence of perforation in appendiceal diverticulitis is four times greater and mortality has a 30-fold increased rate compared to that of acute appendicitis [4]. Additionally, appendiceal diverticulosis may facilitate the occurrence of and play a role in the development of pseudomyxoma peritonei in association with mucinous appendiceal tumors [2, 4]. Again, for all cases of appendiceal diverticulosis, management favors incidental appendectomy and thorough gross inspection of the appendectomy specimen with complete histological examination [2, 4].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.