-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Phi H Lu, Nghia H Tran, Cuong Van Nguyen, Hoang Tran Viet, A blunt gallbladder trauma: a rare and easily overlooked case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf276, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf276

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The rate of gallbladder injury in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma is ⁓2%. Furthermore, an isolated gallbladder injury in a case with blunt trauma is even rarer. A 16-year-old female patient fell from the third floor of a secondary school building and was admitted to the Emergency Department with traumatic shock, and multiple organ injuries including head injury, spinal fracture, femur fracture, and blunt abdominal trauma. The patient received initial first aid and diagnostic tests, including blood tests, abdominal ultrasound, and contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography, which revealed a gallbladder injury and free abdominal air. Diagnostic laparoscopy identified a gallbladder hematoma, with no hollow organ rupture. Open surgery was performed to examine the duodenum and digestive tract, revealing no additional organ injuries. The gallbladder was removed, and the patient recovered without complications by day 6 postoperatively, before being transferred for orthopedic surgery.

Introduction

Extra-hepatic bile duct injury is rare among all blunt abdominal injuries. Fizeau first reported the case of common bile duct rupture in 1806. According to current literature statistics, it only accounts for 3%–5% of abdominal injuries [1]. Isolated gallbladder injury/rupture from blunt abdominal trauma is seldom mentioned in literature due to its rarity. The incidence of injury to the gallbladder from blunt abdominal trauma has been reported as 0.5 ± 0.6% of all intra-abdominal injuries. Liver injury is especially likely: (83%–91%) of patients with gallbladder injuries; duodenum and spleen injuries in up to 54% of patients [2]. The isolated gallbladder injury patient described in this article had no other intra-abdominal injuries. This manuscript was prepared following the CARE guidelines.

Case presentation

A 16-year-old female patient fell from the third floor of a secondary school building and was admitted to the Emergency Department with traumatic shock, and multiple organ injuries including a head injury, spinal fracture, femur fracture, and blunt abdominal trauma after the accident 1 h. The patient was hemodynamically unstable (body temperature 37°C; heart rate 120/min; blood pressure 80/50 mmHg; respiration: 22 beats/min). Her physical exam revealed traumatic shock with right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness. Bloodwork revealed an elevated white blood cell count at 14 700 cells/μL, low hemoglobin at 9.0 g/dL, abnormal prothrombin time test result (PT 42%/INR 1.91%) and elevated liver enzymes with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 144 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 427 U/L. Her past medical and surgical history were unremarkable. She had no home medications or any allergies. The patient had received initial first aid and secondary surveys such as broken bones fixed with cast immobilization, pain relief, blood transfusion, and focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST). The ultrasound found gallbladder wall thickening, suspected intra-gallbladder hematoma with free fluid collection in the Morison’s pouch, and no accompanying liver or splenic injury. After recovery from shock, computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast showed a thick-walled gallbladder with some pericholecystic fluid, free abdominal air bubbles, no contrast extravasation, and no evidence of accompanied liver or splenic trauma (Fig. 1).

CT showing thick-walled gallbladder with some pericholecystic fluid, free abdominal air bubbles.

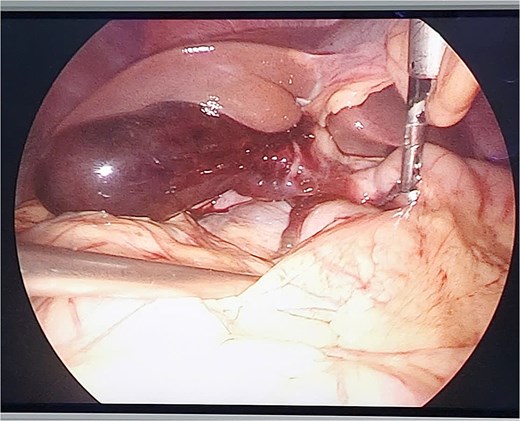

The patient was indicated for diagnostic laparoscopy. During laparoscopic surgery, gallbladder contusion was found and there was a presence of free blood in the peritoneal cavity, but no hollow organ rupture was observed (Fig. 2).

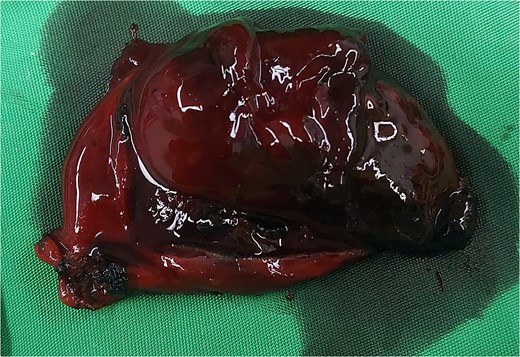

Conversion to open surgery was continuously done to examine the entire duodenum and digestive tract. We explored the omental bursa and then performed Kocher and Cattell-Braasch maneuvers, with any injuries being observed. A cholecystectomy was then performed, followed by cavity lavage with saline, and primary abdominal fascial closure, with abdominal drainage. The patient recovered without complications on the 6 postoperative day and was continuously transferred to The Orthopedic and Trauma Center for broken bone surgery (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Isolated gallbladder injury is an uncommon result of blunt abdominal trauma, occurring in ⁓2% of blunt abdominal trauma cases. Given its relatively protected location, shielded by the liver and rib cage, and its small size, it is seldom injured [3]. Risk factors are conditions that lead to increased gallbladder volume without thickening its walls, like fasting, alcohol consumption, and the absence of gallbladder chronic disease [4]. In this case, the patient had arrived at school early and had not had breakfast when the accident occurred. Under fasting conditions, a large amount of bile secreted by the liver is stored in the gallbladder, which is relatively full. When the abdomen is subjected to blunt violence, the pressure in the bile duct rises sharply, causing gallbladder rupture, which is among the critical factors causing gallbladder injury in this patient, consistent with the common inducing factors of gallbladder injury mentioned by Abouelazayem et al. [5].

Gallbladder injuries include contusion, laceration, and avulsion, with the mechanism involving compressive and shearing forces seen most commonly in motor vehicle collisions. Contusion, defined as intramural hematoma, is most often diagnosed at the time of laparotomy and is probably underreported. Perforation, also known as “rupture” or “laceration,” is the most commonly reported injury. Avulsion, the second most commonly reported injury, has three subtypes: partial avulsion, in which the gallbladder is partially torn from the liver bed; complete avulsion, in which the gallbladder is completely torn from the liver bed but with intact cystic duct and artery; and total avulsion, in which the gallbladder lies free in the abdomen, torn from all attachments [6]. The clinical classification and management of gallbladder injury were described by Smith and Hastings in 1962. Thereafter, the description and treatment were supplemented and revised by Losanoff and Kjossev [7], as shown in the figure below (Fig. 4).

![Losanoff and Kjossev’s classification of gallbladder injury [7].](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2025/5/10.1093_jscr_rjaf276/1/m_rjaf276f4.jpeg?Expires=1773594706&Signature=EPh3Q5E5pwsrv9sSXI1psTPyCijZtJij09J6WQkD~gJ58E1y9vadzQ1pbKedydLMQ7WTJqv71kB0ZVwjHnqlzbp7RH2KzXyCntachM15E8XL2d5vRa1fEvMexcbQnUhQUbfxhYrtlaDBahivFN50iSZoLDXCJt7a4WMkCTJXzZVnhNCi-fKst5H7gn4NlDmEMsRBi1qvvi-YclGdfklzN9rLxZFqGm6nKGdeS4izB8Wph3Nr5WhPKu8VKyber91b-rk~mP-PAQx7RIh3Iav2GRcuu5DhHLJSAxkRoplzySNRVMAer4SbOIxluKCUWsqlQ~ZHeotvdzacrtpZJfmyfg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

Losanoff and Kjossev’s classification of gallbladder injury [7].

Clinical presentations are highly vague with unspecific right hypochondrial pain and can range from an acute abdomen to a slow progression of abdominal symptoms. This can lead to a late diagnosis or delayed surgery several weeks after trauma [8]. In our case, there was free air but no perforation of a hollow organ. Traditionally, pneumoperitoneum strongly indicates hollow viscus perforation, often necessitating urgent laparotomy. However, recent findings from studies like those by Currin et al. highlight that small locules of gas in the abdomen may not always signal perforation but rather represent benign post-traumatic changes, specifically pseudo-pneumoperitoneum. This condition is particularly observed in patients with high-velocity trauma, such as those involved in motor vehicle collisions at high speeds. The mechanisms underlying pseudo-pneumoperitoneum likely involve the “vacuum phenomenon,” where rapid pressure changes during trauma result in the formation of gas within the tissues. Clinically, it is important to distinguish between pseudo-pneumoperitoneum and true pneumo-peritoneum because misinterpretation can lead to unnecessary surgeries, such as exploratory laparotomies [9].

Sonography has played an important role in detection of intra-abdominal injuries with a sensitivity of 86%, a specificity of 98%, an accuracy of 97%, and a negative predictive value achieved ⁓98% [10]. Appreciation and awareness of sonographic findings associated with gallbladder perforation are critical for early diagnosis. These findings include heterogeneous hyperechoic blood inside the gallbladder, ill-defined or thickened gallbladder wall, and distended or collapsed gallbladder with pericholecystic fluid [4]. CT has been proven to be another essential examination method for detecting. Regular CT plain scans can determine whether the abdominal organs are damaged promptly. According to relevant literature reports, enhanced CT is one of the most effective tools for identifying gallbladder injury. Enhanced CT can help determine the diseases of abdominal organs, especially gallbladder stones and intracavitary bleeding, which are difficult to identify on plain scans. This is an essential examination for diagnosing gallbladder injury. Magnetic resonance imaging can effectively identify soft tissue injuries but is unsuitable for patients with acute abdomen because of its long examination time [5].

Cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for gallbladder injuries [10]. Conservative treatment for gallbladder injuries is not recommended and is rarely reported in literature. It seems to be effective in cases of gallbladder contusion with minor tears of the muscular layer of the gallbladder, causing hematoma within the gallbladder. However, most cases of contusion will undergo cholecystectomy due to the risk of perforation from the intramural hematoma progressing to necrosis in an obstructed hydropic gallbladder due to blood clots. Conservative treatment of gallbladder injuries may be a choice in high-risk candidates for surgery, such as in those on therapeutic heparin for a ventricular thrombus induced by atrial fibrillation and end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis with liver and respiratory failure [8]. This case also highlights the importance of early surgical intervention in the case of acute traumatic cholecystitis. Cholecystectomies performed 1–3 days from injury are associated with better patient outcomes, fewer post-operative complications, and shorter hospital stays. Fortunately, our patient had an uncomplicated operative course; however, given that the procedure was five days after the initial injury, the insistence on earlier surgical intervention would have decreased his risk of potential complications [11].

Conclusion

In general, gallbladder injury is uncommon in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Presenting symptoms may be nonspecific, and imaging, such as CT or US, should be utilized to form an accurate assessment and plan for each patient. There is no current standard of treatment for isolated traumatic gallbladder injuries, but early surgical intervention should be considered to minimize the risk of possible complications and subsequent hospital stays.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the support and facilitation provided by the Director of Can Tho Central General Hospital, the Department of General Surgery, and Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, which enabled us to complete this paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interest.

Funding

None declared.

Consent of patient

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

References

- craniocerebral trauma

- blood tests

- hematoma

- bile fluid

- diagnostic techniques and procedures

- emergency service, hospital

- femoral fractures

- first aid

- laparoscopy

- rupture

- shock, traumatic

- surgical procedures, operative

- nonpenetrating wounds

- abdomen

- duodenum

- gallbladder

- spinal fractures

- gastrointestinal tract

- abdominal ultrasonography

- gallbladder injuries

- abdominal ct

- blunt abdominal injuries

- hollow organ

- secondary schools