-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Phoebe C Wood, Katie Lehane, Manju Chandrasegaram, Haemangioma of the small bowel mesentery: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf268, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf268

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mesenteric haemangiomas are a rare manifestation of a common benign lesion. They present a diagnostic dilemma for multiple reasons, namely their low prevalence, vague clinical manifestations and atypical radiological features. However, they warrant investigation and management as they can lead to life-threatening complications such as in the case of rupture and haemoperitoneum. This report details the investigation and management pathway for a 64-year-old female presenting to our institution with a mesenteric haemangioma.

Introduction

Haemangiomas are benign growths, commonly affecting the skin and solid organs [1]. Mesenteric haemangiomas are a rare, diagnostic dilemma. There are ~20 cases reported in the literature [2]. Clinical manifestations are vague, however, can become life-threatening in the instance of rupture [3]. These lesions often have atypical and non-specific radiological features [4]. This case reports describes the clinical manifestations and diagnostic process for a 64-year-old female presenting to our institution.

Case report

A 64-year-old Fijian Indian female presented to the emergency department with 3 days of right lower quadrant abdominal pain, exacerbated by oral intake and associated with light-headedness and 4 kg of weight loss over the preceding month. Medical history included asthma, type 2 diabetes mellitus, reflux, and depression. She had no previous abdominal surgery.

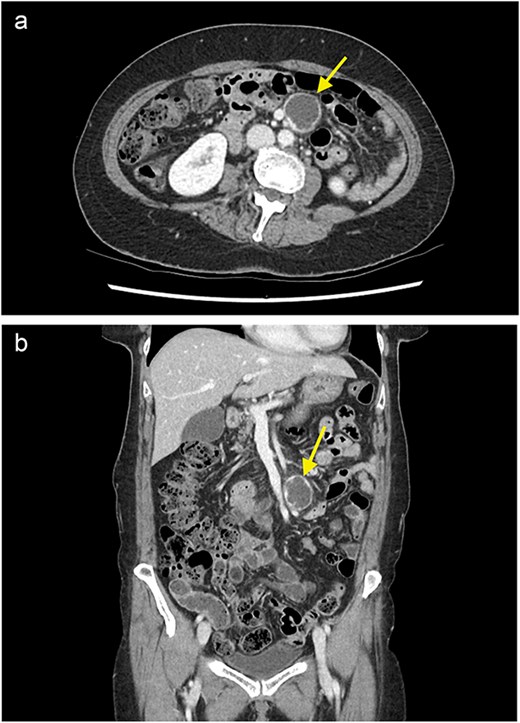

On examination, the patient was haemodynamically stable, and her abdominal exam and preliminary bloods were unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with portal venous contrast revealed an ovoid lesion in the small bowel mesentery, adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery and vein (SMA/SMV) (Fig. 1). The lesion was peripherally enhancing, but centrally hypodense/cystic in nature and measured 32 × 28 mm. Differentials included a necrotic lesion. No other intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal masses were seen. The patient was admitted under the general surgical team for further investigation.

A contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis (portal venous phase) with axial (a) and coronal (b) views demonstrating a cystic lesion in the small bowel mesentery (arrow).

Staging CT of the head and chest excluded distant metastatic disease or lymphadenopathy. Tumour markers were unremarkable. Interventional radiology did not feel the lesion as amenable to biopsy.

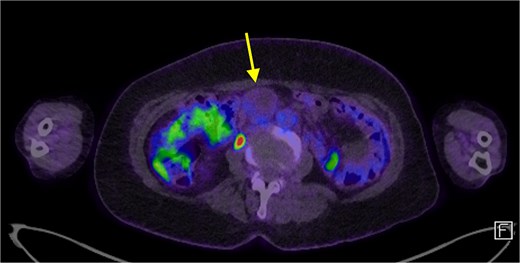

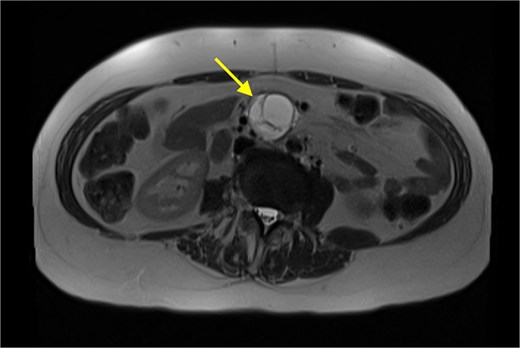

The patient’s symptoms remained stable, and she was discharged with a plan for further imaging. A fludeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan revealed a lesion within the central mesentery with minimal FDG activity, similar to blood pooling (Fig. 2). There was a small region of mild FDG uptake at the posterior margin of the lesion, possibly representing a mural nodule. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed a well-defined T2 hyperintense cystic mass with multiple thick internal septations in the small bowel mesentery measuring 31 × 33 × 34 mm. (Fig. 3) Diagnoses included centrally necrotic pathological mesenteric node, cystic/necrotic neoplasm, cystic vascular, or lymphatic abnormality or infective pathology.

A FDG PET scan in axial view demonstrating a minimally FDG avid lesion in the small bowel mesentery (arrow).

An MRI (T2 HASTE) in axial view demonstrating well-defined T2 hyperintense cystic mass (arrow).

The patient remained largely asymptomatic, and without overt evidence of malignancy, and factoring in the proximity of the mass to the SMA/SMV, the decision was made to observe and repeat CT imaging in 3 months.

The patient underwent serial CT scans and clinical examinations over several months. Symptoms remained stable, however, the second serial CT demonstrated a moderate increase in the size of the mesenteric cystic structure to 40 × 37 × 40 mm. In the context of this interval growth, as well as the patient’s intermittent abdominal discomfort, the decision was made to proceed to a laparoscopic hand assisted excision of the mesenteric mass.

Intra-operatively, the mass was dissected off the SMV and SMA with a combination of ligasure, hydro dissection and diathermy, preserving the vessels. An arterial branch supplying the mass came directly off the SMA. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home.

The mass was sent for analysis. Macroscopically, an intact cystic structure measuring 50 × 35 × 33 mm was examined (Fig. 4a and b). Sectioning revealed a unilocular cyst with a smooth cream lining and wall thickness of 1–3 mm. The cyst contained watery fluid and focal gelatinous substance caked to the lining. No solid areas, papillary excrescences or necrosis was identified.

Macroscopic photographs of the unilocular cystic lesion whole (a) and sliced (b).

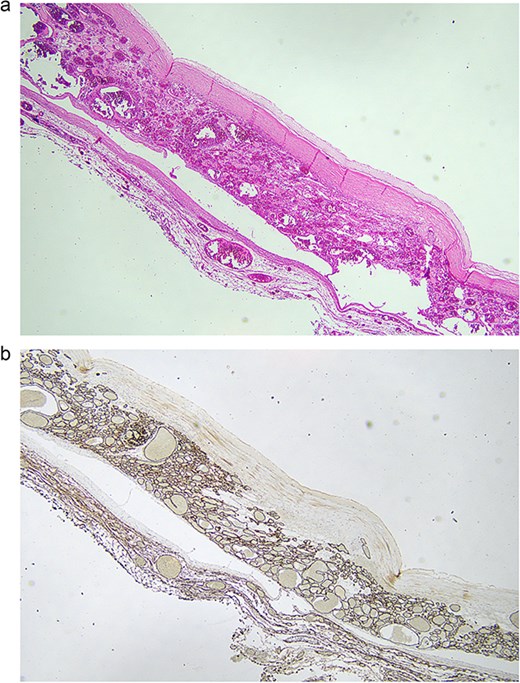

Microscopically, there was a unilocular cystic lesion containing degenerate luminal blood which was loosely adherent to the cyst wall (Fig. 5a and b) The cyst wall had an incomplete hypocellular fibrous layer surrounded by proliferation of variably sized vascular spaces lined with bland endothelial cells lacking architectural complexity. The diagnosis was thought to be consistent with a mesenteric haemangioma.

(a) 2× magnification, routine haematoxylin and eosin sections show a proliferation of variable sized vascular spaces lined by cytologically bland endothelial cells with a central pseudocyst. The pseudocyst has an incomplete hypocellular fibrous wall with no true lining and is filled with degenerate blood. These findings are in keeping with a haemangioma with evidence of a previous haemorrhage forming a central pseudocyst. (b) 2× magnification, CD34 immunohistochemical stain highlights the vascular channels.

The patient recovered well, however described some loose bowel motions. This was not unexpected given the close relationship of the mass to the SMA and surrounding nerves. The diarrhoea was managed with Imodium and the patient was discharged on a subsequent visit to clinic when these symptoms had resolved, with instructions to use Imodium as needed.

Discussion

Haemangiomas are benign vascular hamartomas of mesodermal origin, typically affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissues and solid organs, and rarely originating from the mesentery [1, 4–6]. There are ~20 cases being reported in the literature [2].

Mesenteric haemangiomas present with vague abdominal symptoms, including pain, palpable abdominal mass and a sensation of fullness [3]. Mesenteric haemangiomas may present with obstruction secondary to a mass effect [1, 5]. Mesenteric haemangiomas may not present with gastro-intestinal bleeding, however, can bleed into the mesentery itself. This can be rapid and life-threatening, or occult [1, 3, 5]. Malignant transformation of a gastrointestinal haemangioma is exceedingly rare [1].

Mesenteric haemangiomas have atypical radiological features. They lack the well-defined shape and contrast retention of other haemangiomas [4, 6]. Ultrasound and CT may demonstrate a solid mass with nodular appearance, however MRI is more often diagnostic [4]. Sometimes MRI imaging of these lesions is similar to that seen in hepatic haemangioma with homogenous high T2 signal intensity [7]. However, T2 intensity can vary depending on the presence of fibrosis, haemorrhage, calcification or old blood [4, 8]. Selective visceral angiography has also been used to demonstrate pathological vessels and can be diagnostic and therapeutic in cases of active bleeding [5, 9].

Pre-operative diagnosis of this condition is uncommon [3]. If the diagnosis is made pre-operatively then management may include sclerotherapy, cryosurgery, radium implantation, ablation of arterial supply or low-dose radiation in non-resectable and diffuse disease [1]. There is no evidence of recurrence post-surgical resection [6].

Conclusion

This case outlines the work up of a patient with non-specific clinical and radiological characteristics for a mesenteric haemangioma. Whilst these lesions are not malignant in nature, they can have significant complications such as haemorrhage or obstruction and as such should be considered as a differential in patients with unexplained abdominal pain. This case also highlights an appropriate watch and wait approach given the low severity of symptoms and the proximity of the lesion to large intra-abdominal vessels and therefore possible morbidity associated with an operation.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.