-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gabriel A Molina, Andres V Ayala, Francisco Zavalza, Galo E Jimenez, Diana Parrales, Carlos A Vargas, Mishell A Mera, Emilio F Palacios, Jose M Delgado, Reversal of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass due to malabsorption in a patient with reduced small bowel length, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf241, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf241

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most performed bariatric procedures worldwide. Although the complication rate is low, the benefits gained from surgery outweigh many risks, including malnutrition, electrolyte imbalances, and recurrent marginal ulcers. Since RYGB changes the length of the functioning small bowel and because small bowel length is highly variable, the outcomes, which include weight loss, resolution of medical problems, and development of nutritional deficiencies or limb length, can be highly variable. We present a case of laparoscopic reversal of RYGB. A 52-year-old female patient presented with diarrhea, electrolyte imbalance, and severe weight loss 12 months after RYGB, and a reversal of RYGB was needed to overcome these severe issues. After surgery, she made a full recovery. On follow-ups, she is doing well.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery has emerged as a transformative answer for individuals struggling with severe obesity and its complications, it significantly decreases mortality and morbidity, yet on rare occasions some patients may experience complications due to surgery, such as macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies (1%–26%), which will depend largely on the length of the Roux limb therefore this means that some patients may have too much small bowel bypassed and end up with malnutrition and others end up with a less effective operation. We present a case of a patient with severe weight loss, malnutrition and diarrhea after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). After further evaluation a reversal was needed. After surgery, she underwent full recovery. On follow-ups, she said she was doing well.

Case report

The patient is a 57-year-old female patient with a past medical history of hypertension and morbid obesity. One year earlier, her body mass index (BMI) was 46 kg/m2 (height 165 cm, weight 125 kg) therefore she sought bariatric surgery. She was thoroughly evaluated by a multidisciplinary team and was cleared for a RYGB in another facility without any apparent complications. Nonetheless, a week after the operation, she started having severe diarrhea after every meal.

The diarrheas, which varied between 5 and 6 a day, were bulky, foul-smelling, and greasy. At first, she neglected them since she started losing weight, and mostly due to her carelessness, she missed most of her nutritional and follow-up controls. Over time, the weight loss became even more severe (15 kg in the first month, eight in the second, and then 12 kg on average every two months). As a result, she began to experience generalized edema, was exhausted and slept most of the day. Her skin became loose, and she had issues with walking and eating since every time she ate, diarrhea appeared. One year after surgery, the patient was severely malnourished; her BMI was 17 kg/m2 and she weighed 48 kg; therefore, she was brought by her family to the emergency room.

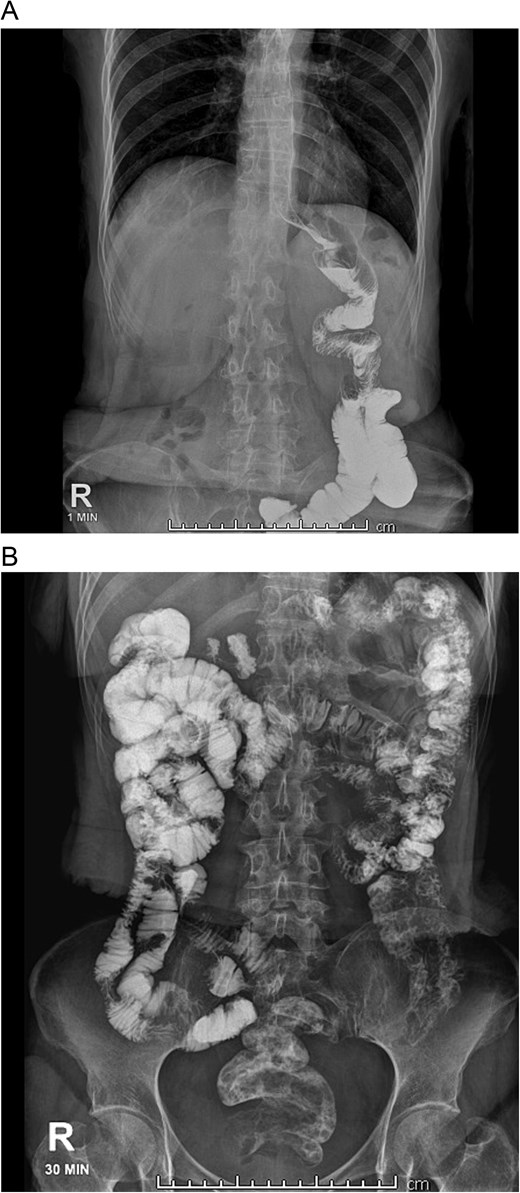

On admission, she was skinny and had bilateral edema in her extremities. Laboratory analyses showed prolonged TP and TTP (20.1 and 57.6 s), anemia (Hb: 7 mg/dl), elevated AST, ALT, GGT, and hypoproteinemia (total proteins: 3 g/dl; albumin: 1.7 g/dl). She was admitted and an endoscopy showed erythematous gastritis in an otherwise standard gastric pouch. The alimentary limb measured 80 cm and appeared normal. An abdominal computed tomography was also done, yet no masses or lymph nodes were found afterward. A bowel transit time test was also performed, which revealed that the contrast reached the anus in <30 minutes (Fig. 1A and B). A quantitative fecal fat test also revealed 9 g/24 h. With these findings, severe malnutrition due to malabsorption after an RYGB was diagnosed.

A: Bowel transit time, the complete alimentary limb and the jejunojejunal anastomosis are seen. B: Bowel transit time, in 30 minutes, it reaches the colon and anus.

She was admitted and placed under a combination of enteral and parenteral nutrition. Despite multiple electrolyte disorders and severe hypoproteinemia, we were able to overcome these issues. After three months, her diarrhea was controlled to one a day, her edema diminished, and finally, her protein levels began to rise (total proteins: 5.2 g/dl; albumin: 3 g/dl).

With these findings, surgery was decided. Among the surgical options considered were a G-tube placement in the remnant stomach, a Henley-Longmire interposition, and complete bypass reversal, which depended on the surgical findings.

On laparoscopy, multiple adhesions were seen between the stomach and the bowel. The whole bowel was counted from the angle of Treitz to the cecum; there, we discovered that the alimentary limb measured 60 cm, the biliopancreatic limb 150 cm, and the common channel 150 cm. The initial size of her intestine was 360 cm, so after the RYGB, she was condemned to severe malnutrition.

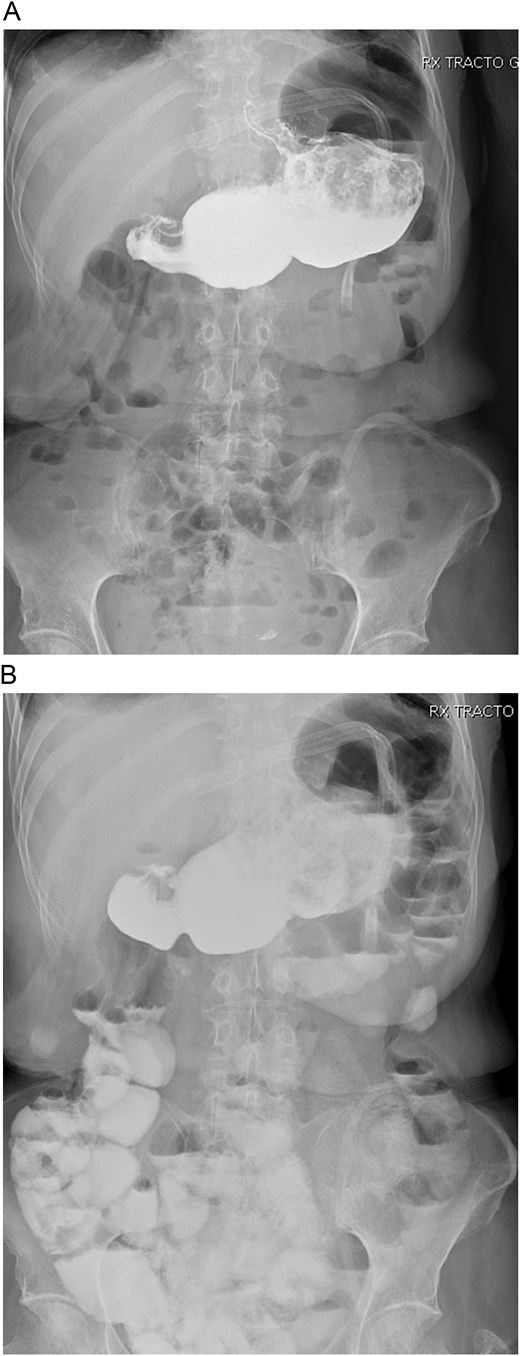

With these findings, a bypass reversal was decided. The alimentary limb was resected from the jejunal-jejunal anastomosis using mechanical staplers (Endo GIA 60 mm purple, COVIDIEN, North Haven, CT, USA), and a latero-lateral gastrostomy was performed between the gastric pouch and the gastric remnant without complications. A drain was placed after a negative methylene blue test, and surgery was completed without complications. Clear liquids were initiated on the first postoperative day without difficulties, and a new bowel transit time was done, which revealed no leaks and that the contrast reached the colon in 10 hours (Fig. 2A and 2B).

A: Bowel transit time, the whole stomach is seen connected. B: Bowel transit time, the whole stomach is seen along with the bowel.

Her postoperative course was uneventful; after no leaks were seen, she was placed on a full diet. Parenteral nutrition was weaned off without complications, and she was discharged on her fifth postoperative day. On outpatient consultation, the drain was removed due to low and serous output, and on follow-ups 6 months after surgery, she is doing well without any diarrhea.

Her BMI is now 20.2 kg/m2, and her weight is 55 kg. Laboratory analyses were better. Her TP and TTP were normal, and she only had mild anemia (Hb: 11 mg/dl). Her albumin was 3.7 g/dl.

Discussion

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been one of the most effective tools and long-term treatments to battle the obesity epidemic [1, 2]. Its benefits include controlling comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension and improving quality of life while reducing overall mortality [1]. While many patients can expect good outcomes, a small subset will suffer postoperative complications; early postoperative complications include leaks, fistulas, and abscesses [1, 3]. Late complications comprise malnutrition, excessive weight loss, dietary non-compliance, substance abuse, and marginal ulcers [1, 3, 4]. It’s estimated that about 25% of patients will need a second intervention, which includes revision, conversions, and reversals [2].

The risk of malnutrition after RYGB is extremely low (1.7%), and thankfully, the most common cause is insufficient oral protein intake, which can be easily fixed; nonetheless, in a few subsets of patients, the bowel length can severely impact the patient outcome [5, 6]. The length of the intestine in humans is highly variable and ranges from 350 to 1000 cm [5]. Attempts have been made to associate sex, weight, and height with the length of the intestine [5, 6]. However, only height has a positive association and the taller the patient, the longer the intestine [6, 7]. This has relevance in bariatric procedures, as measuring the small bowel is the only way to prevent the risk of nutritional consequences in malabsorptive, revisional, and metabolic procedures [5, 6]. Bariatric and laparoscopic surgeons have the tools to measure the bowel with accurate and reproducible methods such as those used in laparotomy [1, 5]. Therefore, caution is paramount when performing these procedures, as a small number of patients will have a small bowel short enough to risk nutritional consequences [5, 6]. In these bariatric and metabolic surgeries, measuring the length of the remaining bowel must be done rather than inferring its length after measuring the excluded portion [5].

The literature regarding reversal is limited [1, 8]. However, since Himpens et al. proved it in 2006, even though these procedures are conceptually and technically challenging, the surgical team must be prepared to meet this demanding operation with higher morbidity and mortality [1]. After an extensive literature search, there are currently no guidelines, and the decision to reverse will be made on a case-by-case basis (<0.5% of patients who undergo bariatric surgery will undergo reversal) [8, 9]. The medical team must consider whether reversing the bypass will also bring back all the comorbidities; however, in certain circumstances, such as a patient with short gut syndrome, pain, hypoglycemia, recalcitrant marginal ulcerations, malnutrition, and electrolyte imbalances, reversal will be the only option that allows the patient to resume normal oral intake and correct life-threatening electrolyte abnormalities without the need for TPN [8–10]. In our case, our patient was severely malnourished, and, in retrospect, perhaps it was also poor patient selection, as she did not seek medical attention until it severely impacted her health. Perhaps also the surgical decision was not appropriate for her bowel type.

Gastrogastrostomy and the Henley-Longmire interposition return the stomach’s normal anatomy to improve absorption and reverse the bypass [1, 8]. If the bowel is too short, the surgical team must also disassemble the anastomosis and rejoin it to restore normal gastrointestinal integrity [1, 8, 9], as we did with our patient. These procedures can be performed using open, laparoscopic, or new endoscopic approaches [1, 2].

Bariatric surgery is complex and requires extensive preoperative and postoperative care, evaluation, and preparation. Screening to improve patient selection and constant postoperative follow-up are key to preventing complications. The technical details of bariatric surgery depend highly on the surgeon’s experience and training to determine the patient’s outcome.

Conclusion

Despite intensive screening and careful patient selection, there will still be patients who will require reoperations such as revisions, conversions, or reversals.

Poor patient selection and lack of follow-up will invariably be burdens that the medical team must address and improve. As bariatrics continue to grow, we must be much more vigilant about ensuring that patients get the best quality of care, as one wrong decision can cost them their lives.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.