-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tai Hato, Hiroaki Kashimada, Masatoshi Yamaguchi, Yoshiaki Inoue, Hiroki Fukuda, Masatoshi Gika, Daiki Kamiyama, Morihiro Higashi, Mitsutomo Kohno, Pulmonary bone marrow embolism caused by robot-assisted lobectomy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf967, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf967

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pulmonary bone marrow embolism is most strongly associated with trauma or chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Embolism associated with robot-assisted lung resection has not been previously reported. A female patient underwent left upper lobectomy with robot-assisted thoracic surgery for lung cancer. On postoperative Day 3, chest X-ray revealed a fracture on the dorsal side of the eighth rib. Her postoperative course was uneventful. Pathology of the resected lung revealed pulmonary bone marrow embolism. Owing to anatomical limitation in the mobility of the dorsal intercostal rib space, there is a risk of rib fracture by the metallic port of the robot. The path from the skin incision to the intercostal space should be directed straight towards the target anatomy, and attention should be given to the direction of movement of the most dorsal port during surgery to avoid rib fractures.

Introduction

Bone marrow embolism is a pathological condition in which bone marrow cells or adipocytes enter the systemic circulation, resulting in embolization throughout the body. There have been reports of fatal bone marrow embolism following thoracotomy [1–3]. However, with the recent use of minimally invasive surgery, the frequency of bone destruction has decreased. Robot-assisted surgery is a form of minimally invasive surgery, but owing to its mechanical nature, there is potential for physical stress on the thoracic cage.

Case report

The patient was a woman in her 60s. She was referred to our hospital after a chest X-ray taken during a routine health checkup revealed a nodule in the left upper lung field. She had no history of smoking. Her medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and osteoporosis. She was taking sitagliptin phosphate hydrate, empagliflozin, and eldecalcitol. She was a housewife with no history of occupational asbestos exposure. She had no known allergies, and her family history was unremarkable. Her height was 152 cm, and she weighed 74 kg. Laboratory tests revealed a random blood glucose concentration of 174 mg/dL and an HbA1c level of 7.2%. Chest computed tomography revealed a 2.5 cm irregular nodule with pleural indentation and air bronchogram in the left S1 + 2c segment. Although a definitive pathological diagnosis of cancer could not be made by bronchoscopy, primary lung cancer of the left upper lobe was suspected.

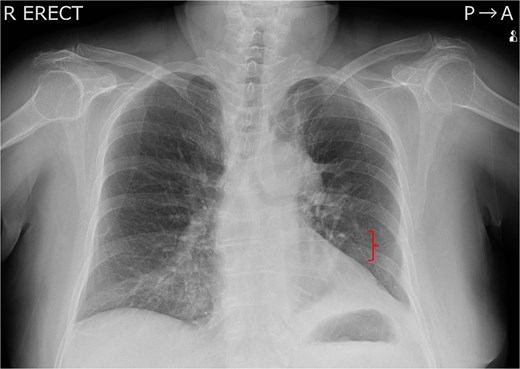

Robot-assisted left upper lobectomy using a portal approach was performed. A 12-mm port was placed near the sternum in the sixth intercostal space, and 8, 12, and 8 mm ports were inserted at the midclavicular, midaxillary, and scapular lines in the seventh intercostal space, respectively. An assistant’s 15 mm port was created near the costal arch in the eighth intercostal space, and CO₂ insufflation was performed at 6 Torr. The remote centre for the posterior port was positioned on the rib near the thoracic cavity, and the port positions were not altered intraoperatively (Fig. 1). The procedure included left upper lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node dissection. The operation time was 3 h, and blood loss was minimal. On postoperative Day 1, the patient presented severe wound pain, requiring two intravenous doses of pentazocine (15 mg) in addition to oral loxoprofen. Her oxygen saturation on room air was 93%. On postoperative Day 3, chest X-ray revealed a rib fracture on the dorsal side of the eighth rib (Fig. 2). On the same day, her SpO₂ improved to 97% on room air, and her respiratory status stabilized thereafter.

Chest X-ray taken on postoperative Day 3. A left 8th rib fracture was observed (bracket).

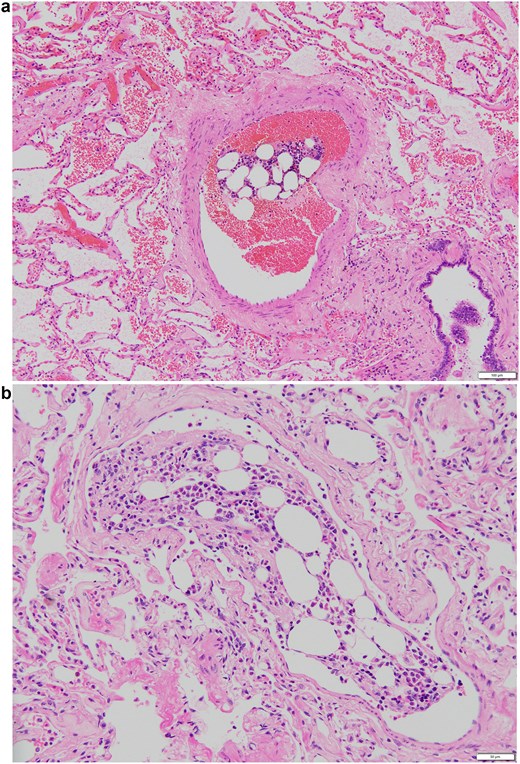

Pathological examination of the resected specimen revealed lung adenocarcinoma. Multiple bone marrow emboli, consisting of fat droplets and bone marrow cells, were identified in the pulmonary arteries of the resected lung (Fig. 3). The size of the emboli varied, and some of the larger emboli measured over 500 mm in diameter on histological sections. There were no fractures other than the rib fracture, suggesting that the intraoperative rib fracture caused bone marrow embolism. Five months after surgery, the patient had no respiratory problems.

Representative images of embolism in the pulmonary artery. (a) An embolism in the relatively large pulmonary artery. The size of the embolism was 540 × 200 mm. (b) An embolism in the pulmonary artery in high-magnification view. The pulmonary embolism measured 290 × 160 mm in diameter.

Discussion

This case represents a rare instance of bone marrow embolism caused by rib injury during robot-assisted pulmonary resection. To our knowledge, bone marrow embolism associated with robot-assisted pulmonary resection has not previously been reported. Bone marrow embolism occurs when mechanical destruction of the bone leads to disruption of the bone marrow vasculature, allowing bone marrow cells and fat droplets to enter the bloodstream. Bone marrow embolism has been reported not only in patients with traumatic conditions but also in patients with nontraumatic conditions such as malignancy, drug abuse, dengue fever, heart failure, and pulmonary hypertension [4–6].

Although thoracic surgery is not considered high-energy trauma, it can impose stress on the bony thorax and occasionally cause bone disruption. Rib fractures occurred in 49% of patients who underwent 20 cm lateral thoracotomy using a Finochietto-Burford rib spreader [7]. There have been reports of fatal bone marrow embolism following thoracotomy [1–3]. Owing to the mechanical nature of the procedure, rib fractures can occur during robot-assisted surgery, sometimes causing clinical problems [8]. To the best of our knowledge, no reports have investigated the frequency of rib fractures sustained during robot-assisted surgery. Rib fractures sustained during robot-assisted surgery are often single fractures near the port site, and the amount of bone marrow released is presumed to be small, making fatal outcomes unlikely. Arai et al. reported that the extent of bone destruction is correlated with the size but not the number of bone marrow emboli [9]. In a retrospective study of traumatic multiple rib fractures and respiratory complications, the incidence of respiratory complications was 16.4% in patients with one or two rib fractures [10]. In cases of iatrogenic trauma during surgery, the mechanical force involved is presumed to be lower, so the likelihood of symptomatic bone marrow embolism is even lower. Nevertheless, pulmonary bone marrow embolism can cause persistent hypoxemia and should be considered a complication to avoid.

Remote centre technology is an advanced technique, but because the port fulcrum is fixed, excessive force may be applied to the ribs when instruments are moved cranially or caudally. The metal ports of surgical robots are rigid, and in patients with thick subcutaneous tissue, the skin and subcutaneous tissue overlying the ribs may be compressed between the port and the rib, directly transmitting pressure to the bone and causing fractures. The dorsal intercostal spaces are narrow, and the costovertebral joints have limited mobility, increasing the risk of rib injury. It is vital to ensure that the path from the skin incision to the intercostal space is directed straight towards the target anatomy and to pay attention to the direction of movement of the most dorsal port during surgery to prevent rib fractures.

Conclusion

With the increasing use of robot-assisted surgery, there is a growing possibility of thoracic injuries that were once rare in patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery. Careful consideration of port placement and intraoperative manipulation is essential to avoid this complication.

Acknowledgements

American Journal Experts performed English proofreading.

Author contributions

T.H. contributed to case collection and manuscript drafting. D.K. and M.H. performed the pathological diagnosis. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.