-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elisabeth Barrar, Christian M Simon, Husain Abbas, Biliopancreatic limb obstruction secondary to 9 cm gallstone nearly two decades following open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and cholecystectomy: a rare and challenging case, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf968, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf968

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of chronic cholelithiasis and an exceedingly uncommon cause of bowel obstruction following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), particularly after cholecystectomy. We report the first known case of a large gallstone causing obstruction of the biliopancreatic limb in an 80-year-old woman with prior RYGB, cholecystectomy, and choledochoduodenostomy. She underwent successful open enterolithotomy with stone extraction. This case highlights the diagnostic and technical challenges posed by altered post-RYGB anatomy and emphasizes the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in similar presentations. Early recognition and individualized operative management are critical to achieving favorable outcomes in this rare but potentially life-threatening condition.

Introduction

Mechanical small bowel obstruction following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is typically caused by internal hernia, adhesions, or anastomotic stricture. Gallstone ileus is a much rarer etiology, accounting for less than 0.3% of cases [1]. It generally arises from a cholecystoduodenal fistula that allows a gallstone larger than two centimeters to migrate and obstruct the intestinal lumen, most often at the ileocecal valve [2, 3]. Gallstone ileus occurring after cholecystectomy is exceedingly rare [4]. Altered anatomy following RYGB adds significant diagnostic and therapeutic complexity to obstruction due to biliary disease. While the literature contains few reports of gallstone ileus after bariatric surgery, this case is, to our knowledge, the first involving obstruction of the biliopancreatic limb by a large gallstone following RYGB, cholecystectomy, and choledochoduodenostomy. This report underscores the need for early recognition and individualized surgical planning in such scenarios.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old woman presented with 4 days of progressively worsening abdominal pain and new-onset nausea. Over the preceding 2 months, she had been evaluated at multiple hospitals for similar complaints. Her surgical history included RYGB in 2005, cholecystectomy in 2019, laparoscopic-assisted transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with choledochoduodenostomy for retained common bile duct (CBD) stones, and abdominoplasty. She was scheduled for open CBD exploration at another facility but presented to our institution due to worsening symptoms.

Her medical history included atrial fibrillation on apixaban, type 2 diabetes mellitus (HgbA1c 6.3%), hypertension, and medically treated gastrojejunal ulcerations.

On examination, she was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Her abdomen was mildly distended with epigastric tenderness and firmness. Laboratory workup revealed moderate leukocytosis (13.3 × 109/l), elevated lipase (288 U/l), and normal total bilirubin (0.8 mg/dl). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated distention of the remnant stomach, duodenum (biliopancreatic limb), CBD, and intrahepatic ducts. A 9.0 × 3.4 cm heterogeneous mass was visualized in the duodenum, consistent with an obstructing gallstone (Figs 1–3).

CT demonstrating gallstone within the common bile duct 1 month prior to this admission.

(a and b) CT demonstrating gallstone in D3-D4 with BPD limb obstruction.

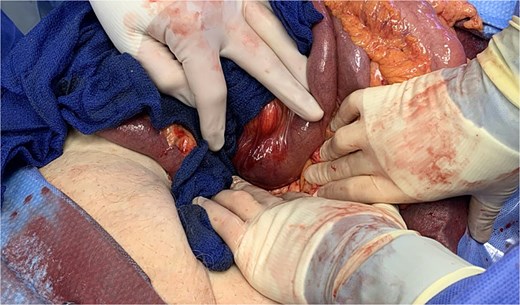

She was resuscitated and taken for urgent exploratory laparotomy due to significant bowel distention precluding safe laparoscopy. Intraoperatively, the bowel was examined retrograde from the ileocecal valve to the jejunojejunostomy and along the biliopancreatic limb. A large gallstone was found impacted between the third and fourth portions of the duodenum (Fig. 4). The ligament of Treitz was divided to mobilize the distal duodenum, as the stone could not be manipulated proximally or distally.

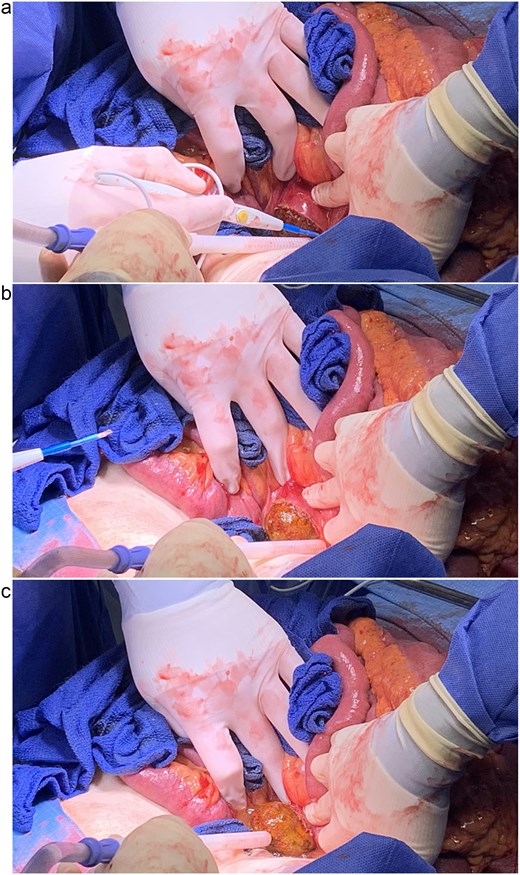

A longitudinal duodenotomy was made for stone extraction (Fig. 5), and the enterotomy was closed transversely in two layers with 3–0 polydioxanone barbed sutures (Fig. 6). A well-vascularized omental flap from the transverse colon was secured over the repair using a modified Graham patch technique. A closed-suction drain was placed anterior to the repair and a 24-French gastrostomy tube was inserted into the gastric remnant for decompression (Fig. 7).

(a, b, and c) Extraction of gallstone via longitudinal duodenotomy.

Postoperatively, the patient had an uneventful recovery. Her diet was gradually advanced, and the gastrostomy tube was maintained to gravity. She was discharged on postoperative day 4. At 2-month follow-up, she was tolerating a regular diet, and both her drain and gastrostomy tube had been removed without recurrence of symptoms.

Discussion

This case highlights a rare postoperative complication in patients with complex biliary and bariatric surgical histories. Gallstone formation is a well-recognized consequence of rapid weight loss following bariatric surgery, occurring in up to 38% of patients [5]. This risk has prompted debate over prophylactic cholecystectomy during bariatric surgery. However, current guidelines recommend against routine cholecystectomy unless symptomatic. Some studies advocate for the postoperative use of ursodiol to reduce gallstone formation, though evidence remains inconclusive [1, 5–7]. Notably, cholecystectomy is more frequently required following RYGB (14.5%) compared to sleeve gastrectomy [8].

Gallstone ileus typically results from chronic inflammation leading to fistula formation, most often between the gallbladder and duodenum. Stones larger than two centimeters have a higher likelihood of becoming impacted, usually at the ileocecal valve, though obstruction may occur in the jejunum or duodenum [2, 3]. Elderly women are particularly at risk, with a 4.5-fold higher incidence than men [9]. Symptoms often mimic bowel obstruction, including intermittent pain, nausea, and vomiting. CT is the preferred imaging modality, and Rigler’s triad—pneumobilia, mechanical obstruction, and ectopic gallstone—is pathognomonic [10]. Mortality rates can reach 18% in elderly patients with comorbidities, emphasizing the importance of timely diagnosis and surgical management [11].

Gallstone ileus following cholecystectomy is exceedingly rare and may result from retained stones, subtotal cholecystectomy, or spilled gallstones that erode into the bowel [4]. In this patient, the choledochoduodenostomy likely facilitated antegrade migration of a retained CBD stone into the duodenum, leading to biliopancreatic limb obstruction. The altered post-RYGB anatomy further complicated diagnosis and limited endoscopic options.

A methodical intraoperative approach is crucial in post-RYGB patients with obstructive pathology. Beginning at the ileocecal valve and running the bowel retrograde provides a reliable anatomic starting landmark to identify the cause of obstruction. In this case, the stone’s size and location made it difficult to mobilize proximally into the remnant stomach or distally into the jejunum. Dividing the ligament of Treitz allowed for mobilization of the duodenum and facilitated repair. Placement of the gastrostomy tube enabled proximal decompression of the remnant stomach to protect the suture line, while an omental patch provided reinforcement and likely contributed to the patient’s rapid recovery.

Gallstone ileus, though rare, should remain on the differential in RYGB patients presenting with signs of bowel obstruction, even years after cholecystectomy. The altered anatomy of bariatric surgery complicated diagnosis and limited non-operative management options. Prompt imaging, high clinical suspicion, and individualized surgical intervention are critical to achieving favorable outcomes in this complex patient population.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.