-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdullah S Al-Darwish, Muath Alasheikh, Hamad S AlSaeed, Eyad A Hijan, Mohamed S Essa, Muhaid ALNujaidi, Muath AlRashed, Beyond childhood curiosity: foreign body ingestion as a diagnostic blind spot in adolescent small bowel obstruction—a single-center case series and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf901, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf901

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Foreign body ingestion (FBI) is well recognized in young children but less frequently reported in adolescents, particularly those with intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, or behavioral challenges. This group is at increased risk for intentional or impulsive ingestion, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and morbidity. We describe three adolescents with distal bowel complications following FBI. Case 1: a 14-year-old boy with intellectual disability developed small bowel obstruction after ingesting a plastic doll part, requiring laparotomy. Case 2: a 16-year-old boy with behavioral difficulties ingested a plastic bag fragment causing ileal obstruction, managed by enterotomy. Case 3: a 22-year-old woman with untreated mood dysregulation ingested a 4-cm nail that passed spontaneously under conservative management. FBI in this population may present as unexplained obstruction. Radiolucent plastics are often missed on plain radiography, whereas linear metallic objects may pass safely. Early computed tomography, timely surgical intervention, and psychiatric support are essential for improved outcomes.

Introduction

Foreign body ingestion (FBI) is a common pediatric emergency, most frequently occurring in children under 5 years of age [1]. Adolescents are less commonly affected but are at particular risk when underlying conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), or psychiatric illness are present [2, 3]. In these groups, ingestion may be intentional, repetitive, or impulsive, increasing the risk of hazardous outcomes [3, 12].

Although 80%–90% of ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously, 10%–20% require endoscopic removal, and fewer than 1% necessitate surgery [1, 2, 10]. Once a foreign body traverses the pylorus, the risk of small bowel impaction increases, particularly if the object is large, irregular, sharp, or indigestible [4, 5]. Radiolucent items such as plastics pose diagnostic challenges, as they are often missed on plain radiographs [6].

We present three adolescents with underlying behavioral or psychiatric vulnerabilities who developed distal gastrointestinal complications from FBI. We also review the literature on FBI in adolescents with ASD/ID, highlighting diagnostic pitfalls, management principles, and preventive strategies.

Case presentations

Case 1—Plastic doll arm causing jejunal obstruction

A 14-year-old boy with mild ID ingested a detachable plastic doll arm during repetitive self-stimulatory play. Initially asymptomatic, he developed bilious vomiting, abdominal distension, and constipation 3 days later. Examination revealed dehydration, periumbilical tenderness, and distension. Abdominal radiographs showed multiple air–fluid levels suggestive of small bowel obstruction, but no foreign body was visualized. Computed tomography (CT) confirmed a radiolucent intraluminal mass in the distal jejunum (Fig. 1).

Intraoperative photograph showing the plastic doll just after extraction.

At laparotomy, the doll arm was retrieved via enterotomy. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on day five with psychiatric counseling arranged.

Teaching point: Radiolucent plastics are often invisible on plain films; CT should be performed early in adolescents with unexplained small bowel obstruction [6].

Case 2—Plastic bag fragment lodged in ileum

A 16-year-old boy with documented behavioral difficulties ingested a plastic sandwich bag. He presented 2 days later with colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, and distension. Radiographs showed dilated loops with a distal transition point. CT revealed obstruction in the distal ileum, but no clear intraluminal object was identified.

Conservative management with bowel rest and nasogastric decompression failed. Laparotomy revealed a folded plastic bag impacted in the distal ileum, which was removed via enterotomy (Fig. 2). Recovery was uncomplicated.

Intraoperative photograph of the retrieved folded plastic bag causing distal ileal obstruction.

Teaching point: Adhesive obstruction is often presumed in adolescents with prior surgery, but FBI should be considered, particularly when symptoms persist or imaging is inconclusive [4, 10].

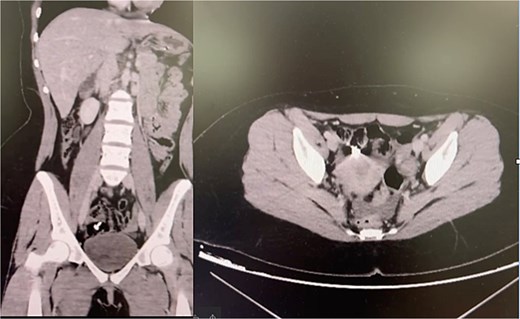

Case 3—Metal nail in the colon

A 22-year-old woman with suspected mood dysregulation ingested a 4-cm nail. Abdominal radiographs revealed a metallic foreign body in the right lower quadrant; CT confirmed its location in the cecum (Fig. 3). She remained asymptomatic and was managed conservatively with a high-fiber diet and serial abdominal imaging. The nail passed uneventfully within 72 h.

Teaching point: Not all sharp objects mandate immediate surgery. Small, linear metallic items may pass spontaneously under close monitoring, but vigilance is essential to detect perforation or obstruction [7–9].

Discussion

Epidemiology and risk populations

FBI is most common in young children under age five [1]. However, adolescents with developmental delay, ASD, or psychiatric disorders remain vulnerable due to impulsivity, sensory-seeking behavior, or self-harm tendencies [2, 3, 12]. Recurrent intentional ingestion has been described in psychiatric populations, leading to frequent admissions and costly interventions [11].

Diagnostic challenges

Most ingested objects pass without incident [1]. However, once an object enters the small bowel, the risk of impaction rises, especially at anatomical narrowings such as the duodenojejunal flexure, mid-ileum, or ileocecal valve [4, 5]. Radiolucent objects, such as plastics, are particularly difficult to detect with plain films [6]. CT has become the diagnostic gold standard for localizing ingested objects and assessing obstruction or perforation [6].

Management principles

Conservative management is reasonable in stable patients without peritonitis or perforation, but persistent obstruction beyond 24–48 h should prompt surgical intervention [10]. Our first two cases required laparotomy after failed conservative management. In contrast, metallic objects may occasionally pass spontaneously if they are small and linear [7–9].

Surgical intervention should be tailored to minimize risk, with laparoscopy preferred where feasible, and conversion to laparotomy indicated in cases of dense adhesions, large objects, or perforation risk [13, 14].

Multidisciplinary approach and prevention

Psychiatric evaluation is critical in adolescents with FBI to address underlying behavioral or mental health issues and reduce recurrence [3, 11, 12]. Caregiver education, environmental modification, and close follow-up are also essential preventive strategies [11, 12].

Literature review

Published cases confirm that adolescents with ASD/ID often ingest non-food objects, commonly radiolucent or sharp, and may present late with obstruction or perforation [2, 3, 11, 12]. Our three cases reinforce these findings and highlight the importance of early CT and individualized management strategies (Table 1). Reported cases of FBI in adolescents with autism/ID.

Reported cases of foreign body ingestion in adolescents with autism/intellectual disability.

| Author/year . | Population . | Object(s) . | Complication . | Management . | Teaching point . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai et al., 2003 [2] | Teen with ASD | Coins | Gastric impaction | Endoscopic removal | ASD patients may repetitively ingest metallic objects |

| Palta et al., 2009 [3] | Young adults with psychiatric illness | Plastics & sharp items | SBO in 12% | Surgery in 12% | Recurrent intentional ingestion is common |

| Chua et al., 2013 [12] | Adolescents with ASD | Metallic objects | Ileal perforation (1 case) | Laparotomy | Adolescents may conceal ingestion until late |

| Alexander et al., 2018 [11] | Adolescents with recurrent ingestion | Mixed plastics/metal | SBO, perforation | Endoscopy/surgery | Recurrence is costly and frequent |

| Current series (2025) | Adolescents with ID/behavioral issues | Plastic doll part, plastic bag, nail | 2 SBO, 1 spontaneous passage | 2 Enterotomies, 1 conservative | Consider FBI in unexplained SBO with radiolucent objects |

| Author/year . | Population . | Object(s) . | Complication . | Management . | Teaching point . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai et al., 2003 [2] | Teen with ASD | Coins | Gastric impaction | Endoscopic removal | ASD patients may repetitively ingest metallic objects |

| Palta et al., 2009 [3] | Young adults with psychiatric illness | Plastics & sharp items | SBO in 12% | Surgery in 12% | Recurrent intentional ingestion is common |

| Chua et al., 2013 [12] | Adolescents with ASD | Metallic objects | Ileal perforation (1 case) | Laparotomy | Adolescents may conceal ingestion until late |

| Alexander et al., 2018 [11] | Adolescents with recurrent ingestion | Mixed plastics/metal | SBO, perforation | Endoscopy/surgery | Recurrence is costly and frequent |

| Current series (2025) | Adolescents with ID/behavioral issues | Plastic doll part, plastic bag, nail | 2 SBO, 1 spontaneous passage | 2 Enterotomies, 1 conservative | Consider FBI in unexplained SBO with radiolucent objects |

Reported cases of foreign body ingestion in adolescents with autism/intellectual disability.

| Author/year . | Population . | Object(s) . | Complication . | Management . | Teaching point . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai et al., 2003 [2] | Teen with ASD | Coins | Gastric impaction | Endoscopic removal | ASD patients may repetitively ingest metallic objects |

| Palta et al., 2009 [3] | Young adults with psychiatric illness | Plastics & sharp items | SBO in 12% | Surgery in 12% | Recurrent intentional ingestion is common |

| Chua et al., 2013 [12] | Adolescents with ASD | Metallic objects | Ileal perforation (1 case) | Laparotomy | Adolescents may conceal ingestion until late |

| Alexander et al., 2018 [11] | Adolescents with recurrent ingestion | Mixed plastics/metal | SBO, perforation | Endoscopy/surgery | Recurrence is costly and frequent |

| Current series (2025) | Adolescents with ID/behavioral issues | Plastic doll part, plastic bag, nail | 2 SBO, 1 spontaneous passage | 2 Enterotomies, 1 conservative | Consider FBI in unexplained SBO with radiolucent objects |

| Author/year . | Population . | Object(s) . | Complication . | Management . | Teaching point . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai et al., 2003 [2] | Teen with ASD | Coins | Gastric impaction | Endoscopic removal | ASD patients may repetitively ingest metallic objects |

| Palta et al., 2009 [3] | Young adults with psychiatric illness | Plastics & sharp items | SBO in 12% | Surgery in 12% | Recurrent intentional ingestion is common |

| Chua et al., 2013 [12] | Adolescents with ASD | Metallic objects | Ileal perforation (1 case) | Laparotomy | Adolescents may conceal ingestion until late |

| Alexander et al., 2018 [11] | Adolescents with recurrent ingestion | Mixed plastics/metal | SBO, perforation | Endoscopy/surgery | Recurrence is costly and frequent |

| Current series (2025) | Adolescents with ID/behavioral issues | Plastic doll part, plastic bag, nail | 2 SBO, 1 spontaneous passage | 2 Enterotomies, 1 conservative | Consider FBI in unexplained SBO with radiolucent objects |

Conclusion

FBI is an under-recognized cause of unexplained small bowel obstruction in adolescents with ASD, ID, or psychiatric illness. Radiolucent objects are easily missed on plain films [6], and sharp objects may occasionally pass spontaneously but carry a perforation risk [7–9]. Key management principles include early CT [6], surgical intervention for persistent obstruction [10], and psychiatric follow-up to prevent recurrence [3, 11, 12]. This case series and literature review reinforce the need for high vigilance and a multidisciplinary approach when encountering unexplained bowel obstruction in vulnerable adolescents.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.