-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tarashene Neetichow, Wirana Angthong, Assanee Tongyoo, Spontaneous bilothorax without previous surgery or trauma, a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 8, August 2024, rjae485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae485

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bilothorax is a rare condition that can lead to severe infection and death. Most cases present with right-sided pleural effusion and the etiology can be biliary obstruction, infection, or iatrogenic complications. The diagnosis of bilothorax is confirmed by the ratio of pleural fluid to serum bilirubin >1. A 33-year-old Asian female presented with progressive dyspnea from right pleural effusion, which was confirmed to be biloma by pleural fluid to serum bilirubin ratio of 15.9. Imaging showed right-sided subdiaphragmatic nodule, which was subsequently biopsied on laparoscopy revealing hemorrhagic endometriotic lesion. However, there was no obvious diaphragmatic defect connecting pleural and peritoneal cavities. Additionally, no biliary leakage was identified by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The treatment included antibiotics, tube thoracostomy, ERCP with stent, thermal ablation of endometriotic nodules under laparoscopy, and hormonal therapy for endometriosis. Bilothorax is rare case itself but the etiology secondary to endometriosis makes this case particularly unique.

Introduction

Bilothorax, characterized by the collection of bile in the thoracic space, is a rare condition with approximately 60 reported cases. The specific diagnostic test is a pleural fluid to serum bilirubin ratio >1 [1]. Bilothorax can lead to serious complications such as empyema thoracis and fibrothorax [2]. Its etiologies are associated with trauma, biliary obstruction, infection, and iatrogenic complications [1, 3]. This case is unique as the patient developed bilothorax without prior surgery or trauma.

Case presentation

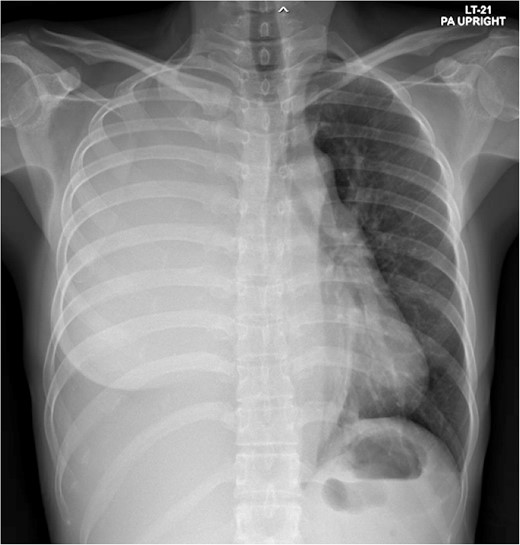

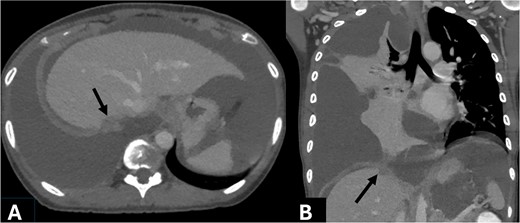

A 33-year-old Asian female presented with progressive dyspnea for 1 month. Physical examination revealed decreased breath sounds at right lung with dullness on percussion and abdominal distension. A chest X-ray showed a large right-sided haziness (Fig. 1). Blood test revealed hemoglobin 11.9 g/dl, WBC 13 200 cells/mm3, protein 8.3 g/dl, albumin 3.5 g/dl, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dl, direct bilirubin 0.13 mg/dl, and alkaline phosphatase 67 U/l. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a large amount of ascites and right pleural effusion, 1.5-cm peritoneal nodule at the right subdiaphragmatic surface (Fig. 2), multiple ovarian cysts, and 2.6-cm hypodense lesion at posterior wall of cervix abutting upper rectum.

Total opacity of right hemithorax caused mediastinum shifting to the left. This finding was consistent with massive right pleural effusion.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast enhanced CT obtained during portovenous phase showed right subdiaphragmatic enhancing nodule attaching right hepatic capsule, measuring 15 mm (arrow). Massive complicated right pleural effusion caused compressive atelectasis at lower part of right lung. Large amount of ascites was noted.

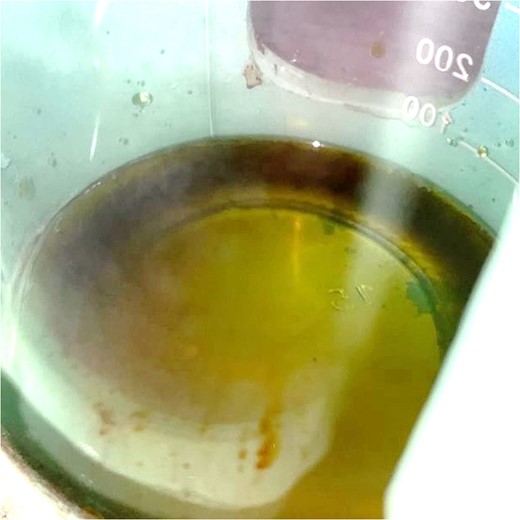

Tube thoracostomy at right chest drained 500 ml of green viscous fluid (Fig. 3). Pleural analysis showed protein 5.8 g/dl and LDH 1194 U/l (serum LDH 170.8 U/l) indicating exudative fluid based on light’s criteria [4]. Bilirubin of pleural fluid was 7.96 mg/dl, which made ratio to serum bilirubin as 15.9, confirming bilothorax. Abdominal paracentesis drained 1000 ml of dark red fluid, which revealed RBC 835 800 cells/μl, WBC 585 cells/μl (PMN 224 cells/μl), bilirubin 7.11, and albumin 2.65 mg/dl. The serum-ascites albumin gradient, <1.1 g/dl, was suggestive for non-portal-hypertensive causes [5]. Bilirubin level in peritoneal fluid was similar within pleural fluid and the ratio to serum was 14.2, which was higher than 3, consistent with bile leakage based on recommendation of International Study Group of Liver Surgery [6].

Thoracentesis revealed the presence of viscous fluid that looked like bile within right pleural cavity.

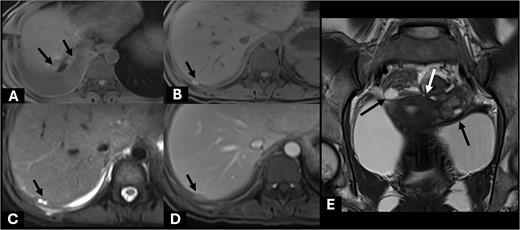

The patient was admitted for intravenous hydration, antibiotics, and close monitoring. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) confirmed a normal appearance of biliary system without bile leakage or fistula. However, few subperitoneal nodules compatible with endometriotic implant nodules were noted (Fig. 4). No major biliary leakage was identified byendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), however, a plastic stent was placed to decompress biliary tract. Further history taking revealed progressive dysmenorrhea over the past year, which was much worsening by expanding from suprapubic area to entire abdomen.

Axial precontrast T1W images (A, B) showed few subhepatic nodules (short black arrow) demonstrating hyperintensity, which measured up to 15 mm abutting posterior right hepatic capsule. It showed hyperintensity on T2W (C) and homogeneous enhancement on post contrast enhanced MRI (D). These findings are suggestive of endometriotic implant nodules with subacute hemorrhagic foci (short black arrow). Included MR pelvis on coronal T2W image (E) showed complex cystic lesions at both adnexae (long black arrow) with adjacent fibrosis (white arrow) creating kissing ovary sign appearance. These findings are compatible with pelvic DIE.

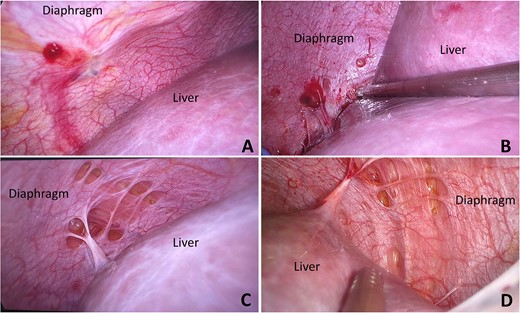

Laparoscopy revealed small hematogenous infiltrative nodules scattering at the right side of diaphragm and falciform ligament, and also multiple punctate lesions at the right dome of diaphragm (Fig. 5). Some peritoneal nodules were biopsied and found to contain endometrial-type tissue embedded within fibrotic stroma. The other hemorrhagic lesions were electrocauterized. After operation, her ascites and pleural effusion resolved rapidly, then both catheters were removed before she was discharged on post-operative day 7. She was also treated with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate by gynecologist. She had been doing well at many follow up visits within a year later.

Hemorrhagic nodules scattered on peritoneal surface of right side of diaphragm, at dome (A) and posterior part (B). Multiple punctate lesions with peritoneal defect were found at dome of right diaphragm (C, D) These punctate lesions had no peritoneal coverage and diaphragmatic muscle fibers could be visualized.

Discussion

Bilothorax, also called “cholethorax” or “thoracobilia,” was first described in 1971 by Williams [1, 7]. Bilothorax typically affects the right pleural cavity and is associated with upper abdominal trauma, biliary obstruction, infection, or iatrogenic complications [3, 8]. However, some case studies showed migration of bile across the diaphragm without obvious pleuro-peritoneal connection [2, 8, 9]. There are two possible mechanisms. First, bile is an alkaline and caustic fluid accompanying with higher intra-abdominal to intrathoracic pressure leads to biliary fluid crossing through diaphragmatic pores. Secondly, bile collection in peritoneal cavity probably drains via lymphatic channels into pleural space.

Initial management includes antibiotics and immediate chest tube drainage. The etiology and location of biliary obstruction or leakage should be investigated by imaging modalities. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy and stenting is required to decompress biliary system and alleviate bile leakage [1, 3]. Laparoscopy or thoracoscopy is helpful to detect pleuro-peritoneal connection and sometimes to provide fistula closure. Surgical repair might be needed especially in a large defect, a fistula associated with abscess, or failed endoscopic treatment [3].

In this case, many evidences supported bilothorax was caused by “diaphragmatic endometriosis,” endometrial tissue implanting on the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic endometriosis was first mentioned by Brews A in 1954. Besides pelvic pain due to coexisting pelvic endometriosis, diaphragmatic endometriosis produces cyclic upper abdominal pain, shoulder pain and even chest pain [10]. The hyperintensity nodules would be demonstrated on fat-suppressed T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The endometriosis located on diaphragmatic surface can infiltrate and penetrate through the thickness of diaphragmatic muscle, then result in pleuro-peritoneal connection or even thoracic endometriosis [11].

The right-sided dominance about 60–70% of diaphragmatic endometriosis, reported by Vercellini P and Piriyev E [12, 13], is probably explained by the theory of clockwise peritoneal fluid flow. The diaphragmatic movement and large bowel peristalsis result in continuous alteration of intraperitoneal pressure, which facilitates fluid flow in clockwise direction [13]. Accompanying with retrograde menstruation known as Sampson’s theory [11], endometrial cells spill out of uterine cavity via fallopian tubes and flow along with clockwise direction to the right-side abdomen. Because this flow would be blocked by falciform ligament, endometrial cells implant mostly at the right leaf of diaphragm.

About bile leakage without detectable biliary tract defect, “deep infiltrating endometriosis” (DIE), which could deeply penetrate into bowel wall resulting in mucosal lesion or even perforation [14, 15], was assumed to penetrate into liver parenchyma causing minor bile leakage. These DIE lesions might be poorly visualized due to tiny size on the dark red surface of liver, and further reduce in size during non-menstrual cyclic interval.

The treatment guideline of diaphragmatic endometriosis was not proposed yet. Initially, hormonal therapy should be started to suppress hormone production of ovaries. Surgery, considered in recurrent or refractory disease, included bipolar coagulation, argon beam coagulation, CO2 laser, or excision [11, 12, 16]. Endometriotic lesions are frequently located at the posterior part of diaphragm, liver mobilization might be needed to allow adequate treatment [16].

Conclusion

Bilothorax diagnosed by a pleural fluid to serum bilirubin ratio >1. The etiologies include biliary obstruction, trauma, and iatrogenic complications. In this case, diaphragmatic endometriosis was likely the cause of pleuro-peritoneal fistula. Deep infiltrating endometriosis into liver parenchyma might result in bile leakage. This is a unique case because bilothorax from diaphragmatic endometriosis has not been reported.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of this case report. Clinical review and case presentation were performed by Tarashene Neetichow and Assanee Tongyoo. Radiologic images and results were prepared by Wirana Angthong. The literature review and discussion were written by Assanee Tongyoo. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

- antibiotics

- stents

- thermal ablation therapy

- dyspnea

- pleural effusion

- biliary leak

- endometriosis

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- laparoscopy

- wounds and injuries

- infections

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- respiratory diaphragm

- peritoneum

- pleura

- magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- pleural fluid

- endocrine therapy

- biliary obstruction

- serum bilirubin measurement

- previous surgery

- tube thoracostomy

- biloma

- asian

- causality

- defect of diaphragm

- serum bilirubin level

- biliothorax