-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Phelopatir Anthony, Nagy Andrawis, Early gastro-oesophageal junction perforation repaired using through-the-scope clips following Nissen fundoplication, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 3, March 2024, rjae194, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae194

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Early gastric and oesophageal perforations are rare following laparoscopic fundoplications, with an incidence of 0.9%. If managed operatively, omentopexy or redo-fundoplication may be employed. Here, we present the case of a septic 21 year old patient who presented with an early gastro-oesophageal perforation 7 days following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, which was successfully repaired endoscopically using haemostatic clips. To date, this technique of perforation repair in the setting of fundoplication has yet to be reported.

Introduction

The 360° laparoscopic fundoplication, known as Nissen fundoplication, is considered the gold standard procedure for gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder (GORD) [1]. With the emergence of laparoscopy, anti-reflux surgery has become the treatment of choice for recalcitrant GORD. However, morbidity is associated with this procedure, with perforation accounting as among the most importantly recognized of complications [2]. In this report, we describe a patient who presented post-fundoplication with an early gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) perforation, which was closed using through-the-scope clips.

Case report

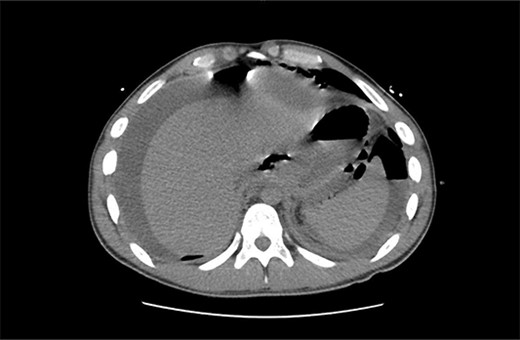

A 21 year old male presented to the emergency department with 1 day of abdominal pain and vomiting. Seven days earlier, a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, posterior cardiopexy, and anterior gastropexy for reflux aspiration were performed. Medical history included a left branchial cyst and asthma. Gastroscopy 3 years prior demonstrated reflux oesophagitis and small hiatus hernia, with no previous surgeries. On examination, blood pressure was 118/85 mmHg, with tachypnoea to 40 breaths per minute and tachycardia to 121 beats per minute. He was peritonitic. Laboratory results demonstrated C-reactive proteinof 543 mg/dL and Lactate of 5.9 mmol/L. He was commenced on intravenous fluid resuscitation and piperacillin-tazobactam. Computed tomography (CT) abdomen demonstrated large amounts of intra-abdominal free fluid, and more than expected pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopy performed 7 days prior, as seen in Fig. 1. Nasogastric tube (NGT) and indwelling urinary catheter were inserted, and the patient was organized for a damage control diagnostic laparoscopy +/− laparotomy.

Non-contrast CT abdomen/pelvis in axial view demonstrating diffuse intra-abdominal free fluid with multiple large locules of intraperitoneal free air.

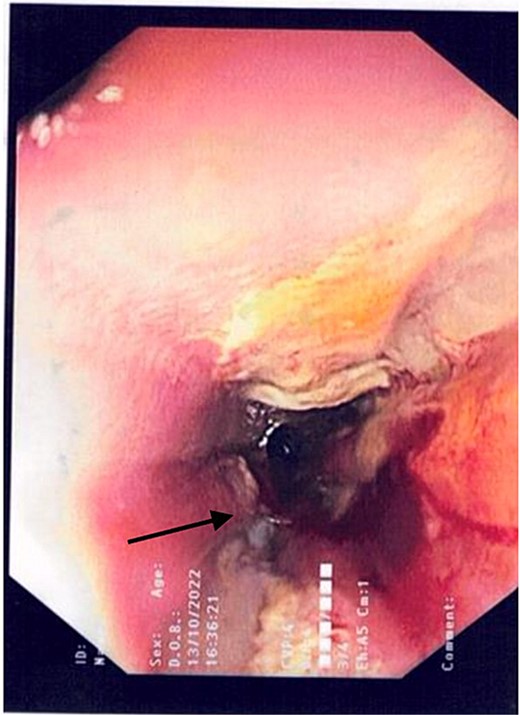

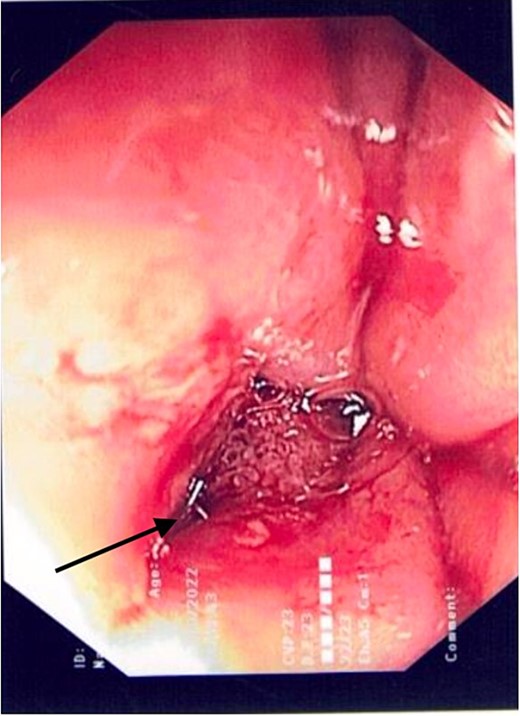

2L of pus was evacuated during laparoscopy, and it was converted to open due to limited views. At this stage, there was no obvious perforation. The entire colon was inspected, following splenic flexure and caecal mobilization. On inspection of the stomach, the wrap was intact with an unremarkable leak test. The decision was made to proceed with gastroscopy, whereby a 3 mm pinhole defect was seen at the GOJ at the 9 o’clock position, as shown in Fig. 2. Three haemostatic Cook Medical Instinct clips were placed, from distal to proximal, ensuring there was stable apposition of the perforated mucosa prior to deploying, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. Following this, the NGT was re-inserted under vision. The midline laparotomy was partially closed and Abthera dressing placed. The patient was taken to ICU intubated, with definitive closure performed 48 h later.

Gastroscopic image demonstrating the pinhole defect of the GOJ at the 9 o’clock position (arrow).

Gastroscopic image demonstrating the successful application of haemostatic clips at the site of perforation (arrow).

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) was commenced immediately post-operatively. His post-operative course was complicated with fevers, necessitating a CT abdomen pelvis on Day 5, which demonstrated ileus with no other complications, such as ongoing leak. The endoscopic clips are noted on this CT in Fig. 4. Indeed, NG feeds were commenced on post-operative Day 7, following ongoing high NG outputs necessitating 2-hourly aspirates. TPN was ceased on Day 13, and he was discharged on Day 14 with oral antibiotics, a thickened fluid diet, and an NGT. On follow up, his NGT was removed, and he was upgraded to a full diet.

Intravenous and oral contrast enhanced CT abdomen/pelvis on post-operative Day 5, in axial view, demonstrating the placement of haemostatic clips at the previous site of perforation (arrow), with no evidence of ongoing leak.

Discussion

The laparoscopic fundoplication, referring to a ‘wrap’ of the gastric fundus anterior or posterior to the intra-abdominal oesophagus, has demonstrated efficacy in the management of GORD resistant to medical management, as well as in patients with repeated aspiration pneumonitis [3] and non-compliance with long-term antisecretory therapy [4]. In our patient, an anterior gastropexy and posterior cardiopexy were performed with fundoplication, whereby the anterior gastric wall was sutured to the anterior rectus sheath, and the phreno-oesophageal membrane and the cardio-oesophageal junction were sutured to the median arcuate ligament, respectively [5]. The decision to proceed with such fixations was informed by the presence of a hiatus hernia, as well as the 6% rate of para-oesophageal hernia formation that is known to occur following Nissen fundoplications [5]. A tension-free crural repair with non-absorbable sutures was also performed in the index operation, so as to prevent post-operative para-oesophageal hernia [5].

Post-operative complications can be classified as early or late. Indeed, early complications, which occur <4 weeks post-procedure [6], include GOJ perforation, bleeding, which is typically secondary to intra-operative short gastric or epigastric vessel injury, pneumothorax, ‘gas bloat’ syndrome, and dysphagia [7]. Late complications manifest as forms of prolonged dysphagia, including post-fundoplication stenosis, oesophageal dysmotility, or gastric ulcers [8].

Perforation following laparoscopic fundoplication can be accounted for by thermal injury to the oesopahgus during paraoesophageal dissection, with this risk accentuated in the setting of extensive adhesions in the patient with peri-oesophagitis. If cardiopexy was performed, ‘pull-through’ from the suture fixing the cardio-oesophageal junction, posterior fundus, and median arcuate ligament has also been reported to result in post-operative perforation [9]. Other reported causes of early perforation post-fundoplication include small vessel ligation of the anterior oesophageal wall during denudation, causing ischaemia and perforation [10].

Perforation can be managed conservatively or operatively. Stable patients with contained perforations can be managed conservatively. Indeed, they should be placed nil-by-mouth, commenced on intravenous antibiotics, proton pump inhibitor therapy, enteral feeds and may also be candidates for percutaneous drainage of collections or pleural effusions on imaging [11]. However, in free perforation, sepsis, or haemodynamic instability, operative management is to be espoused. Primary repair with omentopexy is the most commonly reported surgical management for gastric perforation following fundoplication [12]. In the setting of gastric perforation demonstrating areas of gastric necrosis, subtotal gastrectomy is to be performed [12]. In oesophageal perforation post-fundoplication, redo fundoplication, such as the anterior 270° Thal method, to cover the site of perforation has demonstrated success, as shown by Yano et al. [10] Primary closure of the distal oesophagus should be avoided in large defects, so as to prevent stenosis and further leak.

Currently, the literature reports through-the-scope clips as establishing effective long-term management of only iatrogenic endoscopic oesophageal perforations up to 20 mm, and for perforations in the setting of Boerhaave syndrome [13].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Declarations

Access to Open Access journal articles were facilitated by the University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District.

All authors are in agreeance with the contents of this article.

This article has not been published elsewhere.

Consent to publish

Obtained from patient.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained by the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Ethics Committee.