-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christos D Kakos, Georgios Geropoulos, Ioannis Loufopoulos, Eirini Martzivanou, Robert Nicolae, Reena Khiroya, Nikolaos Panagiotopoulos, Sofoklis Mitsos, Small lymphocytic lymphoma and lung malignancy coincidence in a male patient: a case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 9, September 2021, rjab412, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab412

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lung carcinoma management secondary to chronic lymphocytic leukemia could be quite challenging. We report a case of a 60-year-old male with several co-morbidities, who presented with shortness of breath and persistent cough. A chest imaging showed a right pleural effusion and complete white-out of the right chest cavity. A computed tomography scan revealed consolidation of the right upper lobe with a 6-cm lesion in hilum with complete occlusion of right lobe bronchus. The patient underwent a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, drainage of pleural effusion and pleural and lung biopsy. Talc pleurodesis as well as a flexible bronchoscopy of the endobronchial lesion was performed. Histopathological examination showed a small B-cell lymphoma of the right pleura and an invasive non-small cell carcinoma of the right lung. Dual neoplasms are challenging in terms of diagnosing, and they usually require a multidisciplinary team for the right treatment strategy, including surgery and chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) represents the most common adult leukemia in the Western world, with men and non-Hispanic whites having a slightly higher risk [1]. Diagnosis is usually made incidentally in a routine blood cell count, with the classic finding of absolute lymphocytosis.

In 1978, Whipham was the first who described a CLL which was complicated by pancreatic cancer [2]. This case was the first proof that CLL is a risk factor for double cancer. Gunz and Angus stated that the risk of a second malignancy simultaneously with CLL was relatively low [3]. However, other authors [4, 5] contradicted the previous statement, claiming that patients with CLL have an upward trend in having a second neoplasm, with cutaneous ones considered to be the most commonly associated.

Here, we report the case of a male patient with small B-cell lymphoma (SLL) of the right pleura, with concomitant squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lung. We also review available literature on such simultaneous malignancies of the hematopoietic and respiratory system.

CASE REPORT

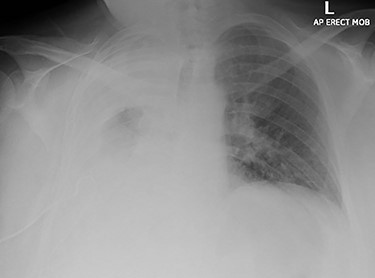

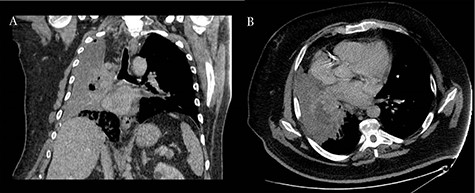

A 60-year-old smoker and obese patient (body mass index: 38.8), with a past medical history of well-controlled hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, Type 2 diabetes and mild lymphocytosis, namely, white blood cell count was 25.67 × 109/l and the lymphocyte rate was 7.60 × 109/l (diagnosed 7 years ago without any further investigation), was admitted to the local hospital complaining of significant shortness of breath and persistent continuous dry cough. Both were present at rest and exacerbated with minimal activity, resulting in decreased ability to formulate a sentence properly. A chest X-ray revealed complete consolidation of the right lung field (Fig. 1). A chest tube was inserted, draining in total 3.8 l, resulting in significant improvement of the patient’s symptoms. Pleural fluid cytology showed lymphocytic effusion with no evidence of malignancy. The chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed consolidation of the right upper lobe with a 6-cm lesion in the hilum completely occluding the right lower lobe bronchus (Fig. 2). The right upper and middle lobe bronchi could not be reliably visualized either.

Chest X-ray imaging of the patient during admission; a wide right sided pleural effusion is depicted.

Coronal (A) and axial (B) CT scans revealing consolidation of the right upper lobe with a 6-cm lesion in hilum; the upper and middle lobe bronchus cannot be reliably visualized and complete occlusion of the right lower lobe bronchus is present.

A right Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) approach was significant for abnormal right pleura, and multiple adhesions between the lung and the chest wall were observed. Large amount of pleural fluid was also drained. Lung and multiple pleural biopsies were sent for cytological and histopathological examinations. Talc pleurodesis was conducted. A flexible bronchoscopy followed, revealing an endobronchial lesion occluding completely the orifice of the right upper lobe bronchus extending to the intermediate bronchus causing partial occlusion of it, as indicated by the previous CT scan. Biopsies from the lesion and bronchoalveolar lavage were sent for examination as well.

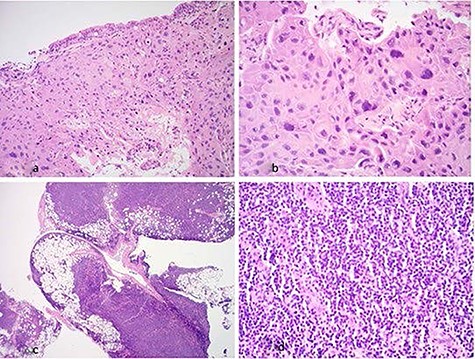

Histology revealed two different pathological diagnoses. The bronchial biopsies showed glandular respiratory mucosa in which the lamina propria was extensively infiltrated by tumor. The tumor comprised sheets of epithelial cells showing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, pleomorphic nuclei with pleomorphic nuclei and intercellular bridges. The features in the bronchial biopsy indicated invasive SCC (Fig. 3a and b). The SCC was characterized as T3N0M0 according to the TNM staging system.

(a) Hematoxylin & eosin (×20 magnification): low-power view showing bronchial mucosa extensively infiltrated by tumor; (b) hematoxylin & eosin (×40 magnification): bronchial mucosa infiltrated by sheets of malignant squamous cells; (c) hematoxylin & eosin (×2 magnification): low-power view of pleura showing dense lymphoid infiltrate which involves adipose tissue; (d) hematoxylin & eosin (×40 magnification): high-power view of pleura showing sheets of small lymphoid cells.

The pleural biopsy showed parietal pleura with attached adipose tissue. The pleura and adipose tissues contained a dense lymphoid infiltrate composed of small lymphoid cells (Fig. 3c and d). Immunohistochemistry showed these lymphoid cells were positive for CD20 with a weak expression of CD5. The lymphoid cells were negative for CD3, CD10, BCL6, cyclin D1 and CD23. The Ki67 proliferation fraction was low, 10%. The lymphoid infiltrate also showed kappa light chain restriction. There were occasional residual follicular dendritic cell meshworks, which were seen with immunohistochemistry for CD21. The features in the pleura were those of a weakly CD5-positive SLL, favoring small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL).The SLL was characterized as Stage 0, low risk, according to the Modified RAI staging, and as Stage A, according to BINET staging.

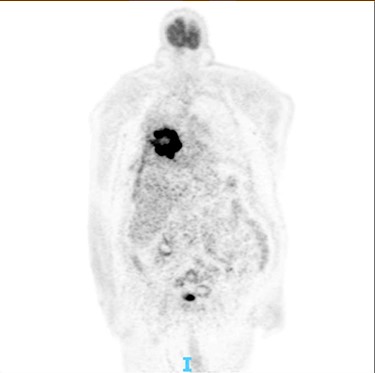

The post-operative recovery was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 7 days after the operation, with aim to start chemotherapy for the lung malignancy. After his discharge, a positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan was conducted in order to give more information about his disseminated lymphoma, without any obvious FDG avid nodal or distant metastasis (Fig. 4). However, the patient passed away 2 months later due to multiorgan failure.

PET scan: there is no obvious cervical, supraclavicular, mediastinal, hilar and axillary lymphadenopathy.

DISCUSSION

Parekh et al. retrospectively studied patients with simultaneous CLL and lung carcinoma over a 20-year period, and they found that ~2% of patients with CLL actually developed lung carcinoma [6]. The same study claimed that 85% of these patients were smokers, males who had a twice risk compared to females and diagnosis of the second malignancy was made on average after 8 years following CLL diagnosis. In addition, up to 38% of these patients will also develop a third neoplasm more likely to the skin (melanoma and basal cell carcinoma), larynx (laryngeal carcinoma) or colon. Most notably, the key factor for survival seems to be the progress of lung carcinoma and not CLL or other types of solid tumor. According to previous findings, Schollkopf showed a significant increase in developing lung cancer in patients with CLL [7].

A possible explanation for this association is the impaired immunity which characterizes patients with CLL due to abnormalities of T and B lymphocytes. Similar conditions are several immunologic deficiencies [8], chromosome aberrations (most common in B-cell CLL patients is 12 trisomy) [9] and patients with organ transplants who receive long-term immunosuppressive therapy [10]. Inheritance has also been accused [11].

There are no specific guidelines for concurrent CLL and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). When the tumors are diagnosed simultaneously, treatment should be targeted to the most aggressive one, as the clinical outcomes depend on the response of the tumor with the poorest prognosis [12]. For this reason, a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory. CLL is generally a disease with slow progression, with an overall median survival of 7 years. On the other hand, metastatic NSCLC represents a more direct threat to survival. As a result, when these two diseases coexist, it seems logical to consider the management of NSCLC as the primary goal of treatment. Accurate staging of lung tumor is crucial for the selection of an appropriate treatment protocol.

It has been reported that complete remission of both diseases could be achieved with a radical approach which comprised of chemotherapy and surgery [13]. The overall survival depends mainly on the stage of lung carcinoma. Patients at Stage I who can tolerate pulmonary resection had favorable outcomes, with a median survival of 33 months [14]. Parekh [6] underlines that the most prominent difference is observed in patients at Stage IIB, with a median survival of 5 months, which is the half from the usual reported for this stage. Surprisingly, survival of Stage IV patients does not significantly differ from the usual reported, but these numerals are already poor, with a 2-year survival estimated to be ~6%.

In our case, the diagnosis of CLL with SCC was simultaneous. However, it is reported that there is usually a delay before the accurate diagnosis of lung cancer, especially in patients with underlying hematological malignancy. This supports the findings of Moertel and Hagedorn [15] that any sign or symptom suggestive of focal malignancy in a patient with leukemia or lymphoma should be managed as representing a primary lesion until pathologically proved otherwise.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

All authors state that no grants and financial support received for this study.

References

- computed tomography

- dyspnea

- pleural effusion

- b-lymphocytes

- carcinoma

- chemotherapy regimen

- chronic cough

- bronchi

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- chronic b-cell leukemias

- lymphoma

- small cell lymphoma

- patient care team

- surgical procedures, operative

- thoracic surgery, video-assisted

- morbidity

- neoplasms

- pleura

- surgery specialty

- lung biopsy

- lung cancer

- carcinoma of lung

- hilum

- fiberoptic bronchoscopy

- thoracic cavity

- interdisciplinary treatment approach

- right lung

- histopathology tests

- talc pleurodesis

- chest imaging