-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Devon Plewman, Rachel Kudrna, Oskar Rojas, Jennifer Ford, Eduardo Smith-Singares, Bilobed gallbladder discovered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a tale of two lobes and one duct, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 12, December 2021, rjab579, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab579

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bilobed gallbladder (BG) is a rare congenital anomaly with just 24 cases documented in medical literature in the past 127 years. There are only three documented cases of BG’s managed with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and in all three cases the bilobed anomaly was discovered preoperatively. We present a case of symptomatic cholelithiasis in a BG that was discovered intraoperatively. Both the surgical techniques used to ensure complete and safe removal of all gallbladder components and the elements associated with the preoperative diagnosis of these rare anomalies are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 1985 and since the early 1990s the procedure has largely replaced open cholecystectomies with about 300 000 performed annually in the USA [1]. Gallbladder duplication is a rare congenital anomaly that occurs in ~1 of 4000 births. BG is a subset of Harlaftis Type 1 gallbladder duplication (Type 1b) and is the rarest of the Type 1 duplications. The first BG described in English medical literature was in 1914 by Deaver and Ashhurst [2]. Since then, there have been a total of 24 BG cases discussed in medical literature. Of those 24 cases, only three of them had symptomatic gallbladder disease and employed the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BGs are a physiological anomaly rather than a pathology, and there is not sufficient evidence to state that BGs are more prone to pathology.

Immediate laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the recommended intervention for patients with symptomatic cholecystitis and is the mainstay of treatment in high income countries. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the highest volume surgeries performed annually with a success rate of 95% and a mortality rate between 0.1 and 0.7% [3]. Discovering the presence of a BG prior to surgical intervention is important for surgeons because of other associated anatomical variations in biliary and vascular anatomy and the potential for injury, but when this cannot be achieved successful outcomes are still possible.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 28-year-old male presented to the ED with constant, severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain of 24-h duration. The pain had been mild and intermittent over the past three weeks. He had been able to manage it with diet and pain medication, but it had intensified over the last day, radiating to his back and epigastric region, and was associated with nausea and vomiting. Per the patient’s report, the pain was exacerbated by oral intake and relieved only by morphine.

Initial vital signs were significant for elevated BP at 138/100. On examination the patient was afebrile with right upper quadrant tenderness, without rebound or guarding and positive Murphy’s sign. His abdomen was soft without distension. Initial lab studies showed elevated WBC at 14.76, elevated AST at 49 and normal bilirubin. Computed tomography (CT) showed cholelithiasis with gallbladder wall thickening and slight pericholecystic inflammation. Ultrasound also demonstrated cholelithiasis with minimal gallbladder wall thickening and a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign was noted. The patient was diagnosed with calculus of the gallbladder with acute cholecystitis without obstruction. He was admitted to the surgical service team with a recommendation for cholecystectomy the following morning.

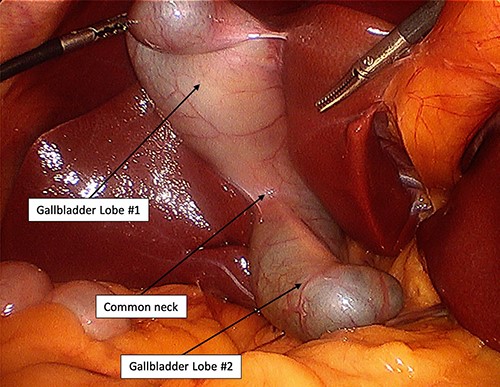

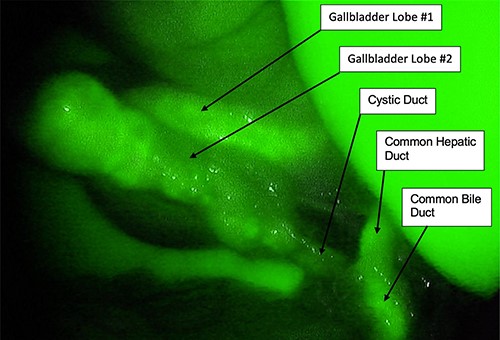

Entry into the abdomen was through an infra-umbilical incision and Veress needle penetration of the fascia. The abdomen was inspected with a 30° angled scope and the fundus of the gallbladder was grasped and reflected superiorly, at which time a second lobe was revealed (Fig. 1). Upon discovery of this anomaly, the fundus of the second gallbladder was retracted to expose the cystic triangle. Blunt dissection was then used to obtain a critical view of safety. There was no evidence of a second cystic duct or other cystic structures. The critical view was confirmed with indocyanine green fluoroscopy, which clearly demonstrated the cystic duct, common bile duct and common hepatic duct (Fig. 2). The cystic duct and artery were occluded with a clip applier before removing both lobes with electrocautery. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications, and the patient was discharged the same day of surgery. Surgical pathology showed chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis without evidence of neoplasia.

Intraoperative indocyanine green fluoroscopy showing a single cystic duct.

DISCUSSION

Gallbladder development begins when the human embryo is 2.5 mm in length (at ~4 weeks). It grows from the liver bud, itself an outgrowth of distal foregut. The liver bud gives rise to the hepatic diverticulum and a smaller diverticulum that will form the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tree. When the embryo reaches 5 mm the hollow primordial gallbladder fills temporarily with endodermal cells and later recanalizes. Some anatomical variations of the adult gallbladder develop when the gallbladder recanalizes incompletely. In the case of a bifid, or bilobed, gallbladder, the incomplete recanalization leaves a longitudinal septum behind. Alternatively, if the recanalization leaves a transverse septum behind, the common Phrygian cap deformity is present. By 6–7 weeks of development the gallbladder is joined to the duodenum by a patent choledococystic duct. Bile secretion begins by the 12th week of development [4, 5].

An anomaly where there is the presence of any portion of an accessory gallbladder is known as gallbladder duplication (first described by Boyden in 1926) [7]. The newer Harlaftis classification (1977) defined two groups. Type 1 gallbladder duplication is classified as two gallbladders that are joined together with a common cystic duct, otherwise known as split primordial gallbladders. Type 1 gallbladders can each have their own independent cystic duct initially but join together prior to joining the common hepatic duct. Type 2 duplications are defined by each accessory gallbladder having its own cystic duct (Fig. 3 [8]). Type 1 gallbladder duplication is much rarer than Type 2, in fact most of the literature reporting on gallbladder duplication describes a Type 2 duplication [9]. In these cases, most cholecystectomies were completed open and used intraoperative cholangiography.

![Harlaftis classification of congenital gallbladder anomalies: (a) septate gallbladder (10.8%) (b) BG (9.5%) (c) Y-shape (24.3%). (d) H or ductular (48.6%) (e) trabecular (2.7%) [6].](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2021/12/10.1093_jscr_rjab579/1/m_rjab579f3.jpeg?Expires=1773307374&Signature=c2M6lkY6KojRmPx~c46Rg3RMxH-4BRs91UErNb3rPubgMzG9WXGkyHG3cmA3mwJu7Qw6-YFlu~tweUrMiBp1bX0Nf5IHbtGC1j~fC3j7rw5Sz0bku~9lt~nZWnBk~BHYyRmyEswYSr3gWDBiaBSetkv1lZGdPbFXc-CPMpuktWBlRhA3o3mEOVyxqZQxNKDj2K9TdbAGwYGIEyfNJ8LPaW~UBt~W8V~rT06KuXjQMSbkfLHKo9b4Am72UnJc45ScLld9TSFi~yRKlIyktCQjmdzacqnk61h2Gq09yPg~jsr6BqP7KfdYUl-RPfSeevLsp6PRji--wxYWrbMb2pOmXQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

Harlaftis classification of congenital gallbladder anomalies: (a) septate gallbladder (10.8%) (b) BG (9.5%) (c) Y-shape (24.3%). (d) H or ductular (48.6%) (e) trabecular (2.7%) [6].

This is the first report of laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed on a BG with gallbladder disease that was not diagnosed preoperatively. The patient had two gallbladder ultrasounds and one abdominal CT, none of which were significant for BG. Postoperative review of the imaging demonstrated a visible septation near the fundus, but this was interpreted as a Phrygian anomaly that would not have affected the surgical plan. Historically, when a case of BG or other biliary anomalies were found the recommendation was to perform an open cholecystectomy. This case demonstrates that intraoperative discovery of a BG can be successfully treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.