-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Narendra Pandit, Abhijeet Kumar, Tek Narayan Yadav, Qamar Alam Irfan, Sujan Gautam, Laligen Awale, Diagnosing gastric volvulus in chest X-ray: report of three cases, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 7, July 2020, rjaa229, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa229

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric volvulus is a rare abnormal rotation of the stomach along its axis. It is a surgical emergency, hence requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent life-threatening gangrenous changes. Hence, a high index of suspicion is required in any patients presenting with an acute abdomen in emergency. The entity can present acutely with pain abdomen and vomiting, or as chronic with non-specific symptoms. Chest X-ray findings to diagnose it may be overlooked in patients with acute abdomen. Here, we report three patients with gastric volvulus, where the diagnosis was based on the chest X-ray findings, confirmed with computed tomography, and managed successfully with surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric volvulus (GV) is an abnormal rotation of the stomach by >180° that usually occurs in association with a large hiatal hernia. It can also occur in patients with an unusually mobile stomach without hiatal hernia. It can be classified as organo-axial (70%) or mesenteroaxial (30%) according to its axis of rotation. It is a life-threatening condition, which requires a high index of suspicion, prompt diagnosis and treatment [1]. The entity is commonly seen in an elderly. The volvulus, if not diagnosed early can progress to strangulation, perforation and sepsis, which is associated with high mortality (30–50%). Hence, it is a surgical emergency [2]. Diagnosis is usually established by computed tomography (CT) scan, upper Gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy or gastrointestinal contrast studies [3]. Chest X-ray findings are frequently overlooked in this group of patients. We describe a series of three patients of GV presenting with an acute abdomen in an emergency where the diagnosis was made by the chest radiograph.

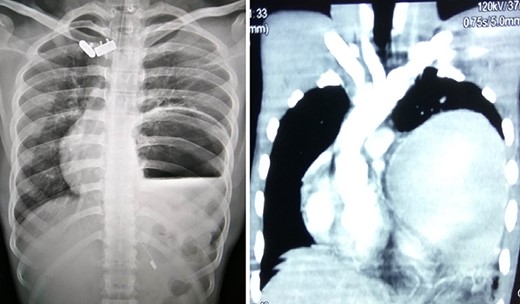

Chest X-ray and CT showing an elevated left hemi-diaphragm with a large sub-diaphragmatic air-fluid level.

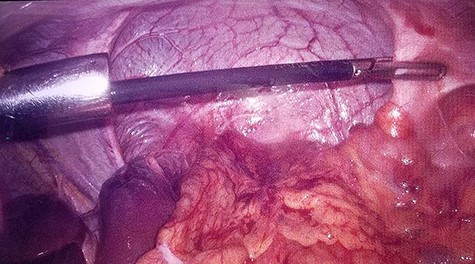

Intraoperative laparoscopic view of left diaphragmatic eventration.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 19-year-old male with no known co-morbidities presented to the emergency department with 2-day history of severe upper abdominal pain and vomiting. He complained of similar episodes over the past 2 years, which used to get relieved spontaneously. On examination, the patient was tachycardic (110 bpm) with normal blood pressure and normothermic. The upper abdomen was asymmetrically distended, non-tender with a tympanic note. The laboratory investigations were within normal limits. Chest X-ray revealed markedly elevated (>4 cm) left hemi-diaphragm, huge gastric shadow with an air-fluid level and shift of mediastinum toward the right side (Fig. 1). Acute gastric volvulus was suspected based on the above finding, which was confirmed with contrast CT. Patient underwent initial laparoscopic evaluation, which was converted to open procedure. Intraoperatively, there was an organo-axial volvulus without any vascular compromise secondary to diaphragmatic eventration. It was de-rotated, decompressed and anterior abdominal wall suture gastropexy done. The freely mobile stomach was further reinforced with sham (trans-seromuscular) gastrojejunostomy. Left diaphragmatic eventration was plicated with polypropylene suture number 1 (Fig. 2) for which it required open conversion. Postoperative period was uneventful and discharged on Day 6. At 16-month follow-up, patient is doing absolutely fine.

Case 2

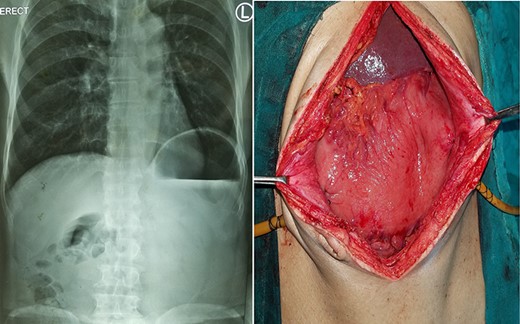

A 75-year-old male presented to the emergency with severe pain in the epigastrium, multiple episodes of non-bilious vomiting and epigastric fullness for the past 2 days. There was no history of weight loss, anorexia, hematemesis or early satiety. Eight months before, he had similar complain (resolved spontaneously), was admitted, and evaluated with upper GI endoscopy and CT abdomen, with normal findings. On examination, patient was tachycardic but normal blood pressure. There was epigastric fullness with mild tenderness. Blood investigations revealed normal hemoglobin, but leukocytosis (16 000 cells/mm3). The renal function test and serum chemistry were normal. Chest X-ray was done, which showed elevated left hemi-diaphragm with large gastric shadow beneath it (Fig. 3). In view of recurring symptoms, chronic gastric volvulus was considered as differentials. On further imaging with CT abdomen, it confirmed gastric volvulus. Patient was taken up for emergency laparotomy. Intraoperatively, organo-axial gastric volvulus secondary to diaphragmatic eventration was seen. It was de-rotated and fixation of the stomach was performed by double, non-draining tube gastrostomy (at two points, body and antrum) with sham gastrojejunostomy to prevent recurrence (Fig. 3). No attempt at the plication of eventration was done due to the technical difficulty, splenic capsular tear and secured stomach fixation. The patient did well postoperatively and was discharged on Day 8. At 38 months follow-up, the patient is asymptomatic.

Chronic gastric volvulus, showing raised left hemi-diaphragm in chest X-ray, with intraoperative placement of double gastrostomy tube for fixation.

Case 3

A 25-year-old-male presented to emergency department with 2 days of abdominal pain and non-bilious vomiting. His vitals were stable. The abdominal examination revealed epigastric fullness. There was no tenderness or organomegaly. The laboratory investigation showed normal hemoglobin (12.6 gm/dl), leukocytosis (18 200 cells/mm3) and normal renal function test and serum chemistry. Chest and abdominal X-ray showed elevated left hemi-diaphragm, grossly dilated and spherical stomach with large air-fluid level occupying whole of the upper abdomen (Fig. 4). The diagnosis of gastric volvulus was made and further confirmed by CT. Nasogastric decompression was attempted, but was futile. Patient was resuscitated, injectable broad-spectrum antibiotic commenced and planned emergency laparotomy. At surgery, organo-axial gastric volvulus was seen lying totally in the abdominal cavity, which was de-rotated and series of anterior abdominal wall suture gastropexy performed to prevent recurrently. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course. He was discharged on Day 7. At 28 months follow-up, the patient is asymptomatic.

X-ray showing a markedly distended and spherical stomach suggesting gastric volvulus.

DISCUSSION

In the present series, we experienced three male patients of organo-axial GV (two young adults and one elderly), none had gastric ischemia, diagnosis was made based on chest X-ray findings, later confirmed by CT scan, and successfully managed by surgery. In all the three cases, the stomach was practically in the abdominal cavity. Two of the patient had GV secondary to the diaphragmatic eventration. Despite its usual association with a large hiatal hernia, it was not seen in any of our patients.

GV is rare to see among the surgical fraternity [4, 5]. The largest series comprises 38 cases in the world published over a study period of 30 years from Brazil [6]. As the entity is rare, a high index of suspicion is required for its early diagnosis and treatment to prevent life-threatening strangulation. The typical clinical presentation in acute gastric volvulus can be severe epigastric pain, abdominal fullness then retching with the inability to vomit [7]. In chronic type, the presentation can be non-specific and remain unnoticed until the acute episode eventually occurs as was seen in the second case [2].

The diagnosis of a GV can be suspected with a good history, physical examination (epigastric fullness, asymmetrical abdominal distention, tympanic note) and simple chest X-ray. However, diagnosis can still be difficult. Plain chest X-ray films can help diagnose and suspect volvulus in any patients presenting with an acute abdomen [5]. It characteristically demonstrates spherical stomach, double air-fluid level or the retrocardiac air-fluid level above the diaphragm on the upright chest films. The elevated left dome of the diaphragm with a large air-fluid level beneath is very much suggesting findings as seen in the present series. Nasogastric tube if in place may appear abnormally in the chest [2, 3]. A barium swallow and upper GI endoscopy may be helpful as an adjunct to chest X-ray, but is time-consuming in an emergency setting, and has been replaced by contrast CT. The CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis with multi-planar reformations confirms the findings of GV in >90% of patients and has been advocated as the primary imaging study [2]. It also provides information about the nature of volvulus, other intraabdominal organs that may be involved, detection of predisposing factors (diaphragmatic defects or hernia) and gastric pneumatosis suggesting ischemia thus assisting pre-operative planning. The characteristic findings suggesting of gastric volvulus in CT scan (with multi-planar reconstruction) are markedly distended stomach filled with gas and fluid, unusually high position stomach, an abnormal axis, or intersection of pyloric antrum and gastroesophageal junction and wandering spleen [8].

Definitive treatment includes immediate operation, as the entity is a surgical emergency, with reduction of the volvulus and prevention of recurrence by repair of any predisposing factors, which remains the gold standard [9]. Traditionally, open surgery has been employed but this problem is suitable for laparoscopic treatment if appropriate skill set of operating surgeon is available [3]. The concomitant anatomical abnormalities (e.g. hiatal hernia and diaphragmatic eventration) need to be fixed. Because hiatal hernia is the leading cause of GV, it should be repaired by reapproximation of the crura or placement of a mesh and fundoplication. The eventration of the diaphragm requires plication; however, if the patient is high-risk, simple gastropexy/tube gastrostomy is preferred. Nonviable or gangrenous areas may demand subtotal or total gastrectomy [2]. Spontaneous volvulus, without an associated diaphragmatic defect/eventration, is treated by detorsion and fixation of the stomach by gastropexy, tube gastrostomy and trans-seromuscular (‘Sham’) gastrojejunostomy [4, 6, 7].

The fixation of the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall is performed with sutures at multiple sites or by the placement of a gastrostomy tube/s (actually serving like gastropexy and postoperative nutrition) and by fundoplication [4]. In GV, fundoplication is used primarily for fixation rather than reflux. Literature suggests either method (gastropexy vs. fundoplication) for stomach fixation with good outcomes. Therefore, which method to be used depends on the surgeon’s preference and the clinical picture (associated hiatal hernia) of the patient [2]. Some high-risk, elderly patients with no gastric compromise can be treated endoscopically with decompression and reduction of the stomach, and placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube to secure the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall [10].

In the present series, due to the lack of expertise, two patients underwent open surgery, whereas one required open conversion from the laparoscopic approach, despite laparoscopic being the preferred approach. Surprisingly, none had hiatal hernia despite organo-axial GV, hence simply managed with detorsion, gastropexy/tube gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy for prevention of recurrence without fundoplication.

To conclude, a diagnosis of gastric volvulus should be kept in mind in any patients presenting to the emergency with an acute abdomen, and a chest radiograph shows elevated left hemi-diaphragm with a large sub-diaphragmatic air-fluid level.