-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mark E Mahan, Imran Baig, Apurva K Trivedi, Jacqueline C Oxenberg, Yakub Khan, Kyo U Chu, Esophageal stent migration to the transverse colon, entrapped within a hiatal hernia status post esophagectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 7, July 2020, rjaa221, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa221

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Self-expandable metal stents are used in both benign and malignant esophageal conditions for the treatment of strictures, leaks and perforations. With this intervention, the most common complication is stent migration. Those in whom migration occurs are subject to additional procedures with significant risk. We present a unique case of stent migration in a 61-year-old male who underwent transhiatal esophagectomy secondary to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Postoperatively, two covered stents were applied to relieve anastomotic stricture and proximal esophageal occluding web. Several months thereafter, the initial stent was found to have migrated to the transverse colon subsequently entrapped in a hiatal hernia defect. Fortunately, the migrated stent was amenable to colonoscopic retrieval. As endoscopic stent use grows, it is important to recognize that covered stents may migrate through anatomic narrowing’s such as pylorus and ileocecal valve, but can also become entrapped in nonanatomic narrowing’s such as a hernia leading to further complications.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal leaks, fistulae and strictures are potentially life-threatening conditions that may be iatrogenic or spontaneous, and depending on circumstance, treat with either surgical or nonsurgical measures. Over the last decade, with advancements in endoscopy, self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) have been used more frequently [1]. Currently, SEMS placement is one of the most common means for palliation of dysphagia caused by benign and malignant esophageal strictures [1]. With this intervention, the rates of related complications are significant, ranging from 22 to 50% [1]. The most common complication following esophageal stent placement is stent migration, occurring in 3.7–50% of patients. Migration probability depends on diameter, covering and materials [2]. Application of suture and clip fixation has been shown to reduce the incidence of migration [3–6]. Despite these advances, the patients in whom stent migration occurs are subject to additional procedures. We present a unique case of esophageal stent migration to the transverse colon entrapped in a hiatal hernia. This case represents the plausibility of stent migration throughout the entire enteric tract, including potential hernias.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male initially presented to the surgical oncology clinic with 4-month history of progressive dysphagia and associated weight loss. Endoscopic ultrasound was performed, confirming a distal esophageal malignancy. He underwent mediport and gastrostomy placement at an outside facility before presenting for multidisciplinary evaluation at our Cancer Institute. Following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, the patient underwent transhiatal esophagectomy with jejunostomy feeding tube placement as well as gastrostomy take down and repair. The final surgical pathology revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, pT2N0. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged home on postoperative day nine.

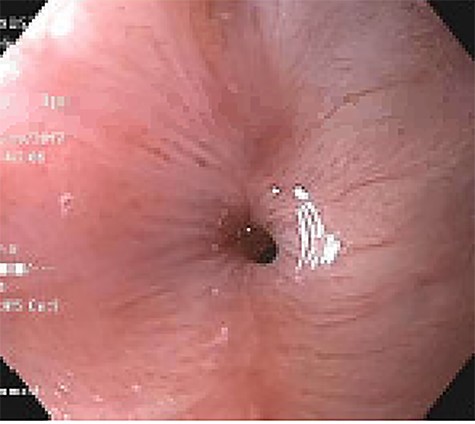

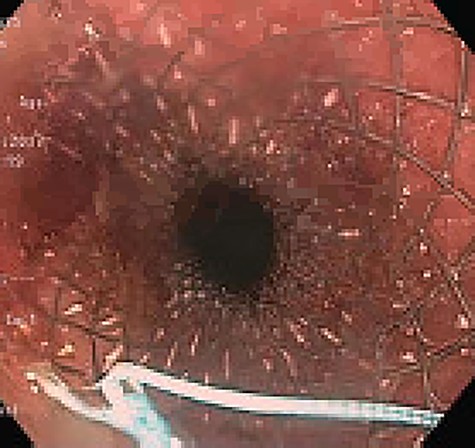

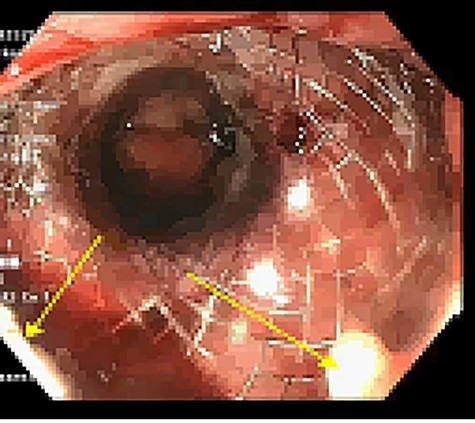

Approximately 2 months into his postoperative course, he returned with symptoms of dysphagia. esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed benign-appearing stenosis at the level of the esophagogastric anastomosis. This was initially dilated with a balloon. However, due to recurrent symptoms, a fully covered SEMS was placed to alleviate stricture (Figs 1, 2). The patient did well for nearly 2 months before returning with recurrent symptoms. A new web was visualized causing complete luminal obstruction (Fig. 3). This was unable to be traversed in antegrade fashion, requiring retrograde access via the jejunostomy utilizing guidewire. A pediatric colonoscope was able to be passed over the guidewire and dilate before subsequent SEMS deployment (Fig. 4). This stent was secured using 2-0 polypropylene suture via Overstitch device (Fig. 5). The initial SEMS was found to have migrated to the mid portion of the gastric conduit. However, due to the small caliber of the proximal stricture and to avoid disrupting newly deployed stent, the initial SEMS was left in place.

Retrograde guidewire, with subsequent pediatric colonoscope and SEMS placement.

SEMS placement across web, secured with 2-0 polypropylene suture via Overstitch device.

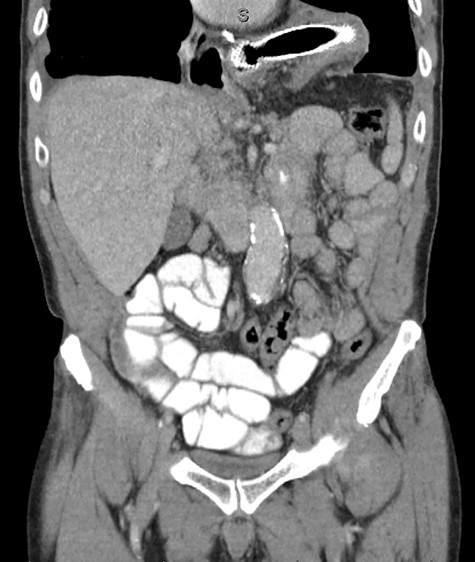

Unfortunately, 6 weeks thereafter he returned with 5-day history of significant abdominal discomfort. He reported tolerance of oral diet without nausea or vomiting. Vitals and laboratory results were unremarkable. However, on computed tomography (CT), initial SEMS had migrated to the transverse colon that herniated into the thoracic cavity via enlarged hiatus (Fig. 6). He underwent upper endoscopy the following morning to ensure the initial stent had not eroded through the gastric conduit into the adjacent colon, as well to ensure adequate positioning of the second stent. Colonoscopy subsequently then proceeded. Although technically difficult the migrated stent was identified and removed with rat-toothed forceps (Fig. 7). His post-procedural course was without complication and he was discharged home the following day with symptom alleviation.

Coronal CT identifying SEMS within the transverse colon, herniated into the thoracic cavity.

Colonoscopic identification of SEMS within the transverse colon.

DISCUSSION

Endoscopic SEMS placement has proven successful for wide variety of benign and malignant esophageal pathologies [1–6]. Anastomotic strictures occur in ~24.5% of those following esophagectomy, requiring balloon dilatation with SEMS placement [7]. The most common complication following esophageal stent placement is stent migration for which occurs in 3.7–50% of cases [2].

As drainage procedures such as pyloroplasty are performed during an esophagectomy, a natural anatomical narrowing is removed; allowing for easier distal SEMS migration. It has been well documented that fully covered stents do not develop tissue ingrowth as partially covered stents, and thus are more prone to migration [2–5]. Similarly, SEMS are more pliable than conventional prosthesis and thus more apt to pass through even anatomic narrowings [3]. When fully covered SEMS are select, clip or suture fixation should be considered to reduce migration rate from as high as 55–15.9% [5].

Following esophagectomy, hiatal hernias have been identified in 0.7–26% of patients [8]. With improved long-term outcome, incidence is expected to increase [8]. Despite this rise, hiatus approximation at time of surgery remains surgeon dependent, without uniform practice. At our institute, as supported by Reich and colleagues, if enlargement of the hiatus is necessary for conduit mobility, it is done so anteriorly rather than laterally to reduce the risk of herniation [9]. Ultimately, the size of the hiatus should be adjusted to the gastric conduit. If the hiatus appears to be too large after gastric pull through, the potential space is reduced with interrupted sutures. Some surgeons tack the conduit to the crus to assist in approximation [8]. However, the over-arching risk with hiatal closure is concern for vascular impediment to the conduit, as damaging or restricting the right gastroepiploic artery has devastating consequences [9, 10].

At the time of hiatal hernia diagnosis surgical repair should be considered [10]. However, as our patient’s symptoms resolved rapidly and completely upon stent removal, decision was made to approach hiatal hernia repair on an elective, outpatient basis.

There are few studies regarding the optimal treatment for migrated SEMS, with little to no data discussing the management of migrated SEMS to the colon. Our case not only describes the successful colonoscopic retrieval of a fully covered SEMS placed for anastomotic stricture, it more importantly demonstrates the ability of SEMS migration through anatomic narrowing’s and entrapment at susceptible nonanatomic defects such as hiatal hernia.

Although our patient only presented with abdominal discomfort that resolved following stent removal, more serious complications such as bowel perforation and sepsis are feared outcomes in scenarios of stent migration with entrapment. As length of survival increases with improved treatments for esophageal cancer, the aforementioned are critical to consider as the incidence of complications related to SEMS will likewise grow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors included have received no financial or other substantive assistance for the funding of this work. All individuals named above have given permission to be named.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.