-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ryohei Ushioda, Atsuko Fujii, Makoto Shirakawa, Tomonori Shirasaka, Shinsuke Kikuchi, Hiroyuki Kamiya, Taro Kanamori, Ventricular septal perforation followed by papillary muscle rupture with acute myocardial infarction: efficacy of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 7, July 2020, rjaa188, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa188

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The occurrence of multiple mechanical complications after myocardial infarction in the same patient may be extremely rare, and the surgical strategy may be very complex because each mechanical complication can be extremely fatal. The case of a patient who underwent repair of a ventricular septal perforation by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), then mitral valve replacement and VA-ECMO for papillary muscle rupture 2 weeks after the ventricular septal perforation repair, is reported. Immediate preoperative stabilization with VA-ECMO may play a crucial role in treating multiple mechanical complications after myocardial infarction.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical complications after acute myocardial infarction (MI) are relatively rare but are potentially fatal pathologies. A sub-analysis of the APEX-AMI trial, in which primary percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 5745 patients, reported that the frequencies were 0.52% for cardiac free wall rupture, 0.17% for ventricular septal perforation (VSP) and 0.26% for papillary muscle rupture (PMR) [1]. However, the occurrence of multiple mechanical complications after MI in the same patient may be extremely rare, and the surgical strategy may be very complex because each mechanical complication can itself be extremely fatal. The case of a patient who underwent VSP repair by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), then mitral valve replacement and VA-ECMO for PMR 2 weeks after the VSP repair, is presented.

CASE REPORT

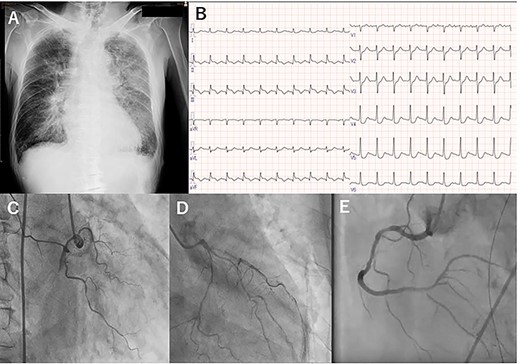

A 76-year-old man presenting with acute onset dyspnea, chest pain and loss of consciousness was referred to our institution. He was a current smoker and had hypertension treated with several antihypertensive agents. His vital signs on admission were blood pressure 117/58 mmHg with support of 7γ of dopamine, heart rate 121 beats/min and SpO2 94% with oxygen at 6 L. Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation were unremarkable on admission. Congestive heart failure (CHF) was found on the initial chest X-ray (Fig. 1A). Troponin T was elevated (4.2 ng/mL), as were CK (722 U/L) and CK-MB (86.4 U/L). The electrocardiogram showed ST elevations in leads II, III and aVF, consistent with acute inferior MI (Fig. 1B). Due to on-going cardiogenic shock, he was treated with an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and mechanical ventilation. Emergent coronary artery angiography showed a completely occluded right coronary artery (RCA), 75% stenosis in the proximal-to-mid portion of the LAD and 90% stenosis in the proximal portion of the left circumflex artery (Fig. 1C and D). The occluded lesion of the RCA was treated with drug-eluting stents (Fig. 1E), and he was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Preoperative chest X-ray (A), electrocardiogram (B) and coronary angiography: right coronary (C), and left anterior descending and left circumflex (D), and right coronary artery (E).

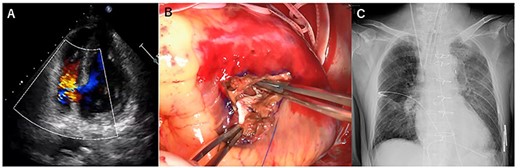

A few hours after treatment, his blood pressure collapsed despite the use of high-dose inotropic support and IABP. On cardiac auscultation, a holosystolic murmur had clearly developed at the left lower sternal border. Since transthoracic echocardiography showed VSP with a left-to-right shunt (Fig. 2A and B), VA-ECMO was started in the ICU and then the patient was transferred to the operating room (OR). Through the median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass was established with aortic and bicaval cannulations, and cardiac arrest was induced with antegrade cold blood cardioplegia. The ventricular septum was approached through the right ventricle parallel to the right posterior descending artery. The VSP was repaired with an extended sandwich patch described by Asai et al. [2] Simultaneous coronary artery bypass grafting to the LAD was also performed using a vein graft. VA-ECMO was removed in the OR, and the IABP was removed on postoperative day (POD) 7. His CHF clearly improved (Fig. 2C), and he was extubated on POD 8.

Transesophageal echocardiography showed a defect with a left-to-right shunt (A). Ventricular septal perforation (VSP) (B). Postoperative chest X-ray (C).

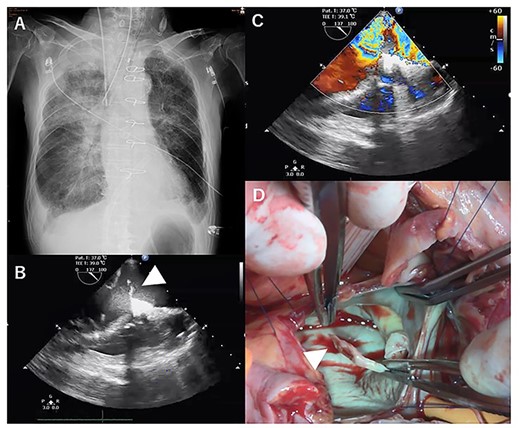

However, he again developed severe cardiogenic shock suddenly on POD 14 (Fig. 3A). Transthoracic echocardiography showed PMR and severe mitral regurgitation (Fig. 3B–D). VA-ECMO was restarted on the general ward, and the patient was transferred directly to the OR. Emergency mitral valve replacement with a biological prosthesis (Magna Ease 27 mm, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was performed in the standard fashion. Intraoperatively, the ruptured posterior papillary muscle was confirmed. VA-ECMO could be weaned immediately after the surgery. After the two emergency operations, his course was uneventful, and he gradually recovered. He was then transferred to another hospital on POD 77 for rehabilitation.

X-ray at 14 days after first operation (A). transthoracic echocardiographic images showing posterior papillary muscle rupture (arrowhead, B) (C). Posterior papillary muscle rupture (arrowhead, D).

DISCUSSION

In the present case, VSP and delayed PMR as mechanical complications after MI in the same patient were treated successfully by emergency operations with preoperative bridge use of VA-ECMO.

As described in the introduction, the incidence of multiple mechanical complications after MI is extremely rare. In the APEX-AMI trial including 5745 patients with ST-elevation MI, there were only three patients who had two mechanical complications. Because each complication can be fatal, there were only reports of pathological studies regarding multiple mechanical complications after MI in the early days [3].

With recent improvements of surgery and perioperative management, however, there have been several reports of survivors of multiple mechanical complications after MI [4–6]. Of these, the report by Levantino et al. [6] was quite similar to the present case. Their 82-year-old female patient underwent VSP repair followed by emergency MVR for PMR on POD 13. However, their patient had a relatively stable hemodynamic condition; the patient was stabilized only with IABP and inotropic support when VSP occurred and without any mechanical support when PMR occurred. On the other hand, the present patient had severe cardiogenic shock with the VSP and the delayed PMR, so VA-ECMO was used each time. Recently, there have been several encouraging reports of preoperative VA-ECMO in patients with post-infarction mechanical complications [7,8], and we consider that the preoperative ECMO therapy may have played a crucial role in the present case.

In conclusion, a rare case requiring repeated surgical interventions for VSP and secondary PMR after acute MI was presented. Immediate preoperative stabilization with VA-ECMO may play a crucial role for treating multiple mechanical complications after MI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.