-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nolitha Morare, Lwazi Mpuku, Zain Ally, Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis complicated by a cholecysto-colonic fistula and liver abscesses, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 7, July 2020, rjaa176, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa176

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 57-year-old male presented to the emergency department with right upper quadrant pain and constitutional symptoms. Initial investigation revealed biliary sepsis with features of chronic cholecystitis, multiple liver abscesses and a fistulous connection between the gallbladder and colon. He was subsequently diagnosed with a cholecysto-colonic fistula, an unusual complication of biliary pathology, with an incidence of 0.06–0.14% at cholecystectomy. It is the second most common form of cholecystoenteric fistula, the first of which is cholecystoduodenal. A preoperative diagnosis was suggested using computed tomography and sinogram imaging. The associated liver abscesses together with the xanthogranulomatous inflammation found on histopathology, makes the case particularly exceptional.

INTRODUCTION

Biliary pathology and the complications thereof are common presentations to surgical departments. Although on occasion the management of these ailments may be challenging, more so is the less proverbial presentation of biliary fistulas [1]. A cholecystocolonic fistula, the second most common enterobiliary fistula, is detected incidentally in ~0.14% of cholecystectomies and will be described in this case [2].

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 2-week history of right-sided abdominal pain associated with weight loss, anorexia and night sweats. On examination he was haemodynamically stable and apyrexial. He had mild pallor but no jaundice or features of chronic liver disease. He had right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness with a 5 cm hepatomegaly. Apart from reduced air entry of the right his systemic examinations were unremarkable.

His liver function tests and septic markers were suggestive of a cholestatic inflammatory process: gamma-glutamyl transferase 318 U/l (<68 U/l), alkaline phosphatase 332 U/l (53–128 U/l), total bilirubin 38μmol/l (5–21μmol/l), conjugated bilirubin 22μmol/l (0–3μmol/l), alanine transaminase 58 U/l (10–40 U/l), aspartate 53 U/l (15–40 U/l), white cell count 13.37 × 109/l (3.92–10.40 × 109/l) and a C-reactive protein of 160 mg/l (<10 mg/l). He had a normal renal function and electrolytes. His human immunodeficiency virus and repeated amoebic and hydatid serology tests were negative.

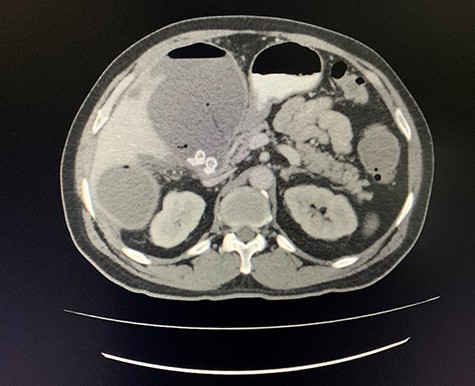

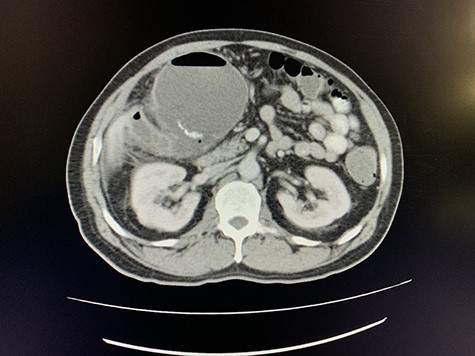

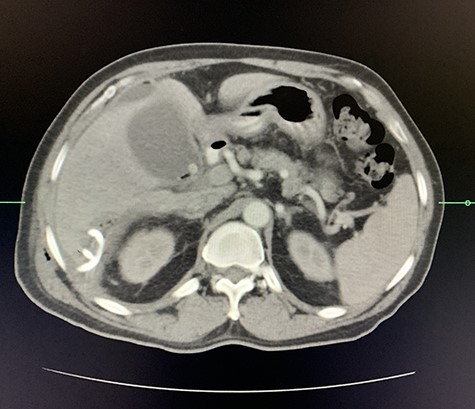

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed an enlarged, thickened gallbladder with multiple stones, communicating with an intrahepatic collection in segment 4 measuring 116 × 80 mm, with an associated air fluid level and air locules (Fig. 1). There was an apparent fistulous tract to the hepatic flexure of the colon, another large collection in segment 6 (97 × 96 mm) as well as other smaller collections (Figs 2 and 3).

Axial view of CT scan of the abdomen with oral contrast demonstrating enlarged, thickened gallbladder with radio-opaque gallstones. Two large liver abscesses in segment 4 measuring 116 × 80 mm (communicating with the gallbladder) and segment 6 measuring 97 × 96 mm with air locules noted.

Axial view of portovenous phase of CT scan of the abdomen demonstrating enlarged, thickened gallbladder with radio-opaque gallstones with apparent fistulous communication with the hepatic flexure of the colon with associated pneumobilia.

Coronal view of oral and intravenous contrasted CT scan of the abdomen demonstrating features of cholecystitis with fistulous communication with the hepatic flexure of the colon with associated pneumobilia.

A colonoscopy performed revealed no tumour nor was the fistula visualised.

A size 12 French percutaneous catheter was inserted into the large liver abscess. The purulent material drained tested negative for organisms, amoebic and hydatid disease (Fig. 4). A sinogram was performed by injecting contrast through the catheter, showing passage into the ascending colon, confirming the initial diagnosis (Fig. 5).

Axial view of arterial phase of CT scan of the abdomen cholecystitis with pneumobilia with resolving liver abscesses with percutaneous pigtail catheter in situ.

Sinogram obtained by anterioposterior x-ray of segment of lower chest/abdomen following injection of contrast into the percutaneous pigtail catheter, demonstrating passage of contrast into the hepatic flexure of the colon via an apparent fistulous connection.

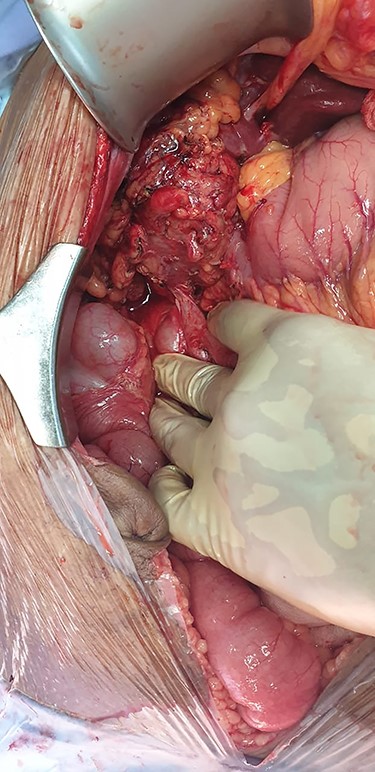

The patient was sent for a laparotomy during which a thickened gallbladder with significant adhesions was noted. A cholecystocolonic fistula was seen involving the proximal transverse colon (Fig. 6). Following adhesiolysis, a cholecystectomy was performed followed by a segmental resection of the colon and fistula with a primary anastomosis of the bowel. The catheter was flushed, and a drain placed into the gallbladder bed. The drain was removed after 4 days, and he was subsequently discharged after recovery.

Intra-operative imaging obtained via laparotomy of the abdomen, demonstrating a fistulous connection between the hepatic flexure of the colon and an inflamed, granulomatous gallbladder.

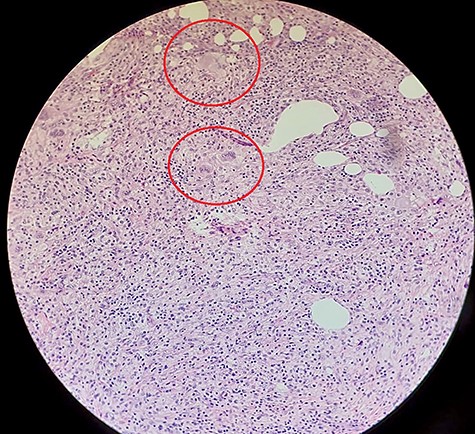

The histopathology revealed an 80 × 50 × 15 mm gallbladder with an ulcerated mucosal surface and irregular fibrino-purulent exudate. A tract extending from the mucosal surface opening on to a portion of bowel measuring 20 mm was noted, comprised primarily of normal bowel mucosa. The microscopic features were suggestive of xanthogranulomatous inflammation with areas of fat necrosis and foamy histiocytes (Fig. 7). Staining for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative, and there were no features of malignancy.

Histopathological slide with hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrating fat (with areas of fat necrosis) and fibrous connective tissue. Dense infiltrate of foamy histiocytes (circled) with associated plasma cells and lymphocytes noted, together with surface ulceration suggestive of chronic xanthogranulomatous inflammation.

DISCUSSION

Internal biliary-enteric fistulas (IBFs) are unusual variants of biliary disease [3–6]. They are found incidentally in 0.14% of cholecystectomy and include the following: cholecystoduodenal (75–80%), cholecystocolonic (8–26.4%) choledochoduodenal, cholecystogastric and cholecystoduodenocolic [3–5].

IBFs have varying aetiology, primarily as a complication of prolonged inflammatory diseases (e.g. cholecystitis, peptic ulcer disease) but may also arise after trauma, malignancy and infection [3, 5]. Clinical presentation is highly variable and non-specific. For this reason, most are diagnosed intra-operatively [3, 5]. In 2009, Savvidou et al. [3] proposed a diagnostic triad of pneumobilia, chronic diarrhoea and vitamin K malabsorption for cholecystocolonic fistulas. This results from the evasion of bile acids from enterohepatic re-absorption, as they bypass the terminal ileum via the fistulous tract opening directly into the colon thus producing bile acid diarrhoea, steatorrhoea and malabsorption of fat soluble vitamins (e.g. vitamin k) [3].

Investigations include: CT, magnetic resonance imaging, barium enema, 99mTc scintigraphy, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). However, these fail to demonstrate the lesion in the large majority of patients [3]. A review by Chowbey et al. [6] in 2006, of 12 428 patients between 1997 and June 2003 who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomies found IBFs in 0.5% (63 patients), 45 patients (71.4%) with cholecystoduodenal fistulas, four patients (6.3%) with cholecystocolonic and 9 patients (14.3%) with cholecystogastric fistulas. A pre-operative diagnosis was suspected in only five patients (0.04%) [6]. More recently, a larger review by Costi et al. [2] from 1950 to 2006 found the incidence to be lower at 0.06–0.14%, probably attributable to the increase in laparoscopy and indications for elective cholecystectomies . A pre-operative diagnosis was made at a much higher rate of 7.9%, possibly attributable to technological advances [2]. Colonoscopy, which failed to make the diagnosis in our case, was attempted in 6/231 cases and only diagnostic in 4, reflecting its limitations [2].

The most significant complications include sepsis, gallstone ileus, obstruction and haemorrhage [2–5]. Liver abscesses, as seen in our case, were only documented in four cases by Costi et al (1.7%) [2]. Other interesting associations in this series included common bile duct (CBD) polyps (0.04%), CBD stones (5%) and cystic artery pseudoaneurysms (0.04%). Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, a rare form of cholecystitis with an incidence of 1.3–5.2%, which was reported in our histopathology, was documented in only one other case (0.04%) [7].

Management includes laparoscopic or open biliary drainage, cholecystectomy and fistula resection (with or without segmental bowel resection and anastomosis) as was done in our case [2, 3, 6, 8]. Hepatic drainage, as was achieved by pigtail catheter in the case, is indicated if the patient has concurrent liver abscesses [2, 6]. Partial cholecystectomy and more extensive subtotal colectomy may be indicated when faced with more complex anatomy. Some authors suggest conservative management with sphincterotomy via ERCP, antibiotics and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation in uncomplicated, asymptomatic cases particularly in patients who are not fit for theatre [3].

In conclusion, cholecystocolonic fistulas are unusual complications of biliary disease, which may be associated with other biliary pathology including, albeit rare liver abscesses and xanthogranulomatous inflammation. One may consider the triad of diarrhoea, vitamin K deficiency and pneumobilia to suggest a preoperative diagnosis if clinical suspicions arise. Imaging is variable and diagnosis is usually made intra-operatively, which forms the mainstay of definitive treatment.

Footnotes

†Address where conducted: Helen Joseph Hospital, Rossmore, Johannesburg, 2092

References

Author notes

Zain Ally and Lwazi Mpuku are co-authors of this study.

- cholecystitis

- sepsis

- computed tomography

- inflammation

- cholecystectomy

- chronic cholecystitis

- pathologic fistula

- hepatic abscess

- emergency service, hospital

- preoperative care

- colon

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- gallbladder

- pathology

- cholecystoenteric fistula

- right upper quadrant pain

- sinogram

- histopathology tests