-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tomohiro Okura, Mototaka Inaba, Isao Yasuhara, Masafumi Kataoka, A case of esophageal rupture caused by long-term exposure to vinegar and resolved by damage control strategies, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 10, October 2020, rjaa392, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa392

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 75-year-old woman had the habit of drinking vinegar. She had emergent transport to our hospital because of vomiting and unconsciousness. The patient underwent emergency surgery for esophageal rupture and septic shock. Intraoperatively, a 25 mm perforated area was found, and the visible esophageal mucosa was black. Because the suture closure or anastomosis was difficult and the shock was prolonged, she was placed in the intensive care unit after undergoing resection of the thoracic esophagus and thoracic drainage. Fifteen hours after the first surgery, we performed external esophagostomy and enterostomy. The third surgery was a retrothoracic cervical esophagogastric anastomosis, and reconstructive surgery was performed 60 days after the first surgery. Prolonged exposure to vinegar may have resulted in esophageal mucosal necrosis. This is a valuable case in which the esophageal mucosa was necrotic, and we performed esophagectomy and reconstruction as a damage control strategy to save her life.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal rupture is an emergency for which early diagnosis and treatment interventions determine the prognosis. The treatment of esophageal rupture is selected from multidisciplinary treatments, esophageal resection and reconstruction. Damage control strategies, including conservative treatment, consider the extent of intrathoracic and mediastinal contamination, time since onset and systemic status. Determining an appropriate treatment is key to saving lives. We report a case of esophageal rupture caused by long-term exposure to vinegar, in which we selected a damage control strategy and performed a three-stage surgery to save the patient’s life.

CASE REPORT

A 75-year-old female had the habit of taking vinegar daily for 50 years. She was transported to our emergency room complaining of vomiting and loss of consciousness. Her medical history included hypertension, and she took amlodipine 10 mg daily. Her family history was negative. Socially, she denied any history of smoking, drug or alcohol use.

On physical examination, she was unconscious, hypotensive and in respiratory failure. Her blood pressure was 86/58 mmHg. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia. Oxygen saturation was 90% (10 L of oxygen administration). No subcutaneous emphysema was observed in the chest. There were no signs of peritoneal irritation. Laboratory data showed a white blood count of 3500. The C-reactive protein level was 8.7 mg/dL, and renal dysfunction was present. Electrolytes, liver function and urinalysis were all within normal ranges.

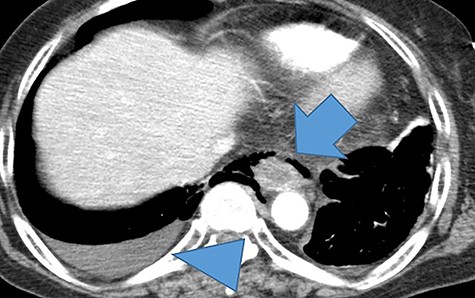

Computed tomography of the thoracic and abdomen with contrast showed poor contrast in the middle intrathoracic esophagus, mediastinal emphysema, right pneumothorax and pleural effusion (Fig. 1).

A thoracoabdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a poorly contrasted area and mediastinal emphysema in the middle and lower esophagus (arrows). Right pneumothorax and pleural effusion are present (arrowhead).

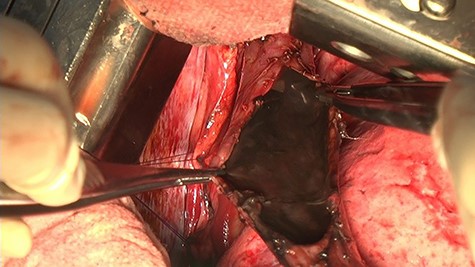

She was diagnosed with septic shock due to esophageal rupture; therefore, we performed emergency surgery. We opened the chest through a posterolateral incision of the sixth intercostal space in the left-sided supine position. The right chest cavity was highly contaminated with fluid containing food residue. We identified a 25 mm perforation site in the middle intrathoracic esophagus. The esophageal mucosa turned black (Fig. 2). We determined that suture closure was not possible and resected the thoracic esophagus by 10 cm. She needed to have an esophageal fistula and an enteric fistula, but because her shock vitals were prolonged intraoperatively, she needed immediate systemic management in the intensive care unit, and the surgery was completed after esophagectomy and intrathoracic lavage drainage as a damage control strategy.

The thoracic cavity was highly contaminated, with a 25 mm perforation of the central thoracic esophagus, and the esophageal mucosa was discolored black all around.

In the excised specimen, the esophageal mucosa was blackened throughout and there were no obvious malignant findings (Fig. 3).

The mucous membrane of the resected esophagus was black in all areas. No malignant findings were found.

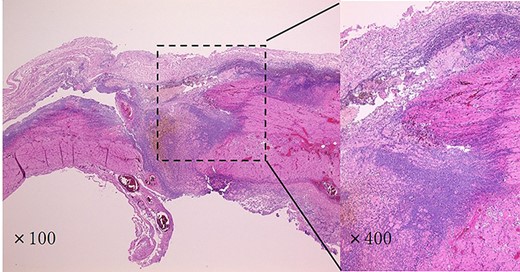

Histopathological examination revealed that the esophageal mucosa was ulcerated and necrotic and perforated in one place. Lymphocytic infiltration was observed in the mucosal surface layer; however, no findings were found beyond the muscle layer. The cause of perforation could not be determined (Fig. 4).

Histopathological findings showed that the esophageal mucosa was ulcerated and necrotic, with perforation in multiple locations. There was a strong lymphocytic infiltration in the submucosa.

Intensive care was started immediately after surgery, and, her vitals were stable 15 hours postoperatively. Therefore, we performed esophageal and enteric fistulae. The esophageal mucosa, which was an esophageal fistula, was also blackened (Fig. 5). Esophageal fistula mucosa normalized on the seventh postoperative day. After waiting for sufficient improvement in her general condition, she underwent esophageal reconstruction by the third operation 60 days after the first operation. We performed a posterior sternal pathway cervical esophagogastric anastomosis and cholecystectomy. She started receiving oral intake on the 12th day and was discharged on the 27th day after the third surgery.

The esophageal mucosa of the esophageal fistula was also blackened.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal rupture is a rare and fatal disease that can lead to mediastinitis and sepsis in severe cases [1]. The causes of the disease were medical in 61%, idiopathic (Boerhaave syndrome) in 15%, foreign body in 12%, traumatic in 9%, and neoplastic in 1% of cases. In addition, perforations of corrosive esophagitis, acute necrotizing esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis have been reported [2–5]. Boerhaave syndrome, corrosive esophagitis, and acute necrotizing esophagitis may be the differential diagnosis in this case.

Boerhaave’s syndrome was first described in 1724 by Hermann Boerhaave [2]. Two common risk factors include alcoholism and excessive indulgence in food. The most common cause is vomiting, which can increase the pressure in the esophagus and cause a barogenic esophageal rupture [6].

Esophageal rupture due to corrosive esophagitis is caused by chemicals such as acids and alkalis. In adults, corrosives are usually ingested for suicidal or deliberate self-harm. The esophageal mucosa turns black, with multiple deep ulcers that lead to necrosis and perforation [7].

Acute necrotizing esophagitis was described by Goldenberg et al. in 1990, as a black esophagus after a cholecystectomy [4]. The etiology is unknown, and multiple factors are thought to be involved, for example, advanced age, sex, diabetes, trauma, malignant tumor and myocardial ischemia [8]. The pathology is a mixture of necrosis and granulation of all layers of the esophageal wall.

Surgical treatment is preferable to the closure of the ruptured area with suture closure and intrathoracic drainage. In cases of the high risk of anastomosis due to high mediastinitis and poor general condition, the two-stage reconstruction technique after esophagectomy has been used in some cases [9].

In our case, there was no history of malignancy, diabetes mellitus, psychiatric disorders, or heavy drinking or corrosive drugs. The characteristic medical history was a history of preference for vinegar for more than 50 years. The mechanism by which vinegar consumption leads to esophageal rupture is unclear. In our case, the residual esophageal mucosa returned to normal after the first surgery, suggesting that vinegar may have played a role in the development of the disease. We suspect that prolonged exposure to vinegar caused necrosis of the esophageal mucosa, and the increased pressure in the esophagus due to vomiting may have led to esophageal perforation.

The damage control strategy is a concept developed as a surgical strategy for trauma treatment, with minimal hemostasis and contamination control, and reoperation is preferable after circulatory stabilization [10]. In our case, due to the high degree of intrathoracic contamination and prolonged shock vitals during the operation, we selected a damage control strategy. She was able to return to society 1 month after reconstructive surgery, and we believe that this treatment strategy was successful. This case demonstrates an important treatment strategy for severe esophageal rupture.

References

- septic shock

- anastomosis, surgical

- enterostomy procedure

- esophagectomy

- esophagostomy

- habits

- intensive care unit

- necrosis

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- shock

- surgical procedures, operative

- sutures

- unconsciousness

- vomiting

- mucous membrane

- surgery specialty

- exposure therapy

- esophagus rupture

- esophageal mucous membrane

- thoracic esophagus

- emergency surgical procedure