-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jarrod Buzalewski, Matthew Fisher, Ryan Rambaran, Richard Lopez, Splenic rupture secondary to amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 3, March 2019, rjz021, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz021

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Splenic rupture in the absence of major trauma is a rare occurrence, which may occur by idiopathic means or a specific pathologic process. One such condition, amyloidosis, involves the extracellular deposition of abnormally folded ‘amyloid’ protein, which can affect the spleen. Protein infiltration in the organ may cause splenomegaly and potentially capsular rupture in advanced cases. We describe a 68-year-old male with a history of end-stage renal disease status-post living donor renal transplant on chronic immunosuppression and Coumadin that presented with abdominal pain, weakness and hypotension. The patient was found to have hemoperitoneum secondary to splenic rupture and was emergently taken for exploratory laparotomy and splenectomy. The pathology of the spleen revealed AL amyloidosis. He was subsequently found to have advanced plasma cell neoplasm by bone marrow biopsy with numerous osseous lytic lesions, consistent with a monomorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous splenic rupture in the absence of major trauma is an infrequently documented phenomenon that requires a high index of clinical suspicion for prompt diagnosis. Unrecognized and untreated rupture results in mortality rates approaching 100% [1]. The etiology of non-traumatic splenic rupture is most commonly secondary to hematologic and/or immunologic processes [1]. One such entity, amyloidosis, is a disease process that involves deposition of extracellular fibrillary protein that leads to progressive organ dysfunction [2]. While amyloidosis may be systemic or localized, splenic involvement is fairly common (5–10%) and generally asymptomatic [3]. When splenic rupture secondary to localized amyloidosis occurs, it is usually the first manifestation of the disease process. This case illustrates spontaneous splenic rupture due to localized amyloidosis as an important consideration in the differential of acute abdominal pain. It also highlights amyloidosis as a potential marker for other systemic disease that may only be recognized or investigated after splenic pathology is elucidated.

CASE REPORT

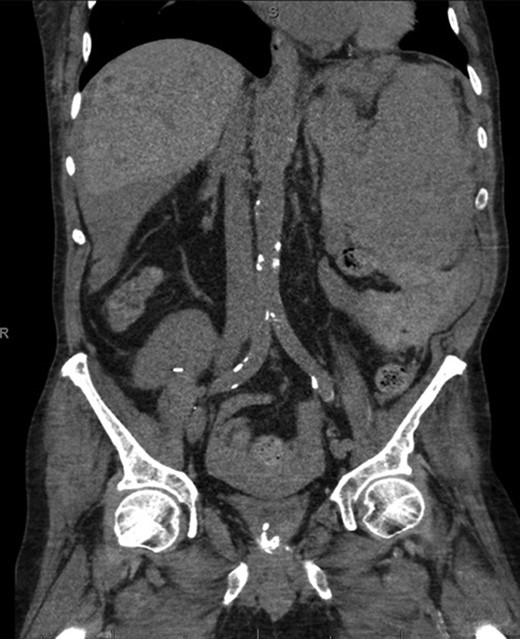

A 68-year-old male with history of living donor renal transplant presented to the ED with acute onset of profound weakness, fatigue, left upper quadrant abdominal pain, hypotension and lactic acidosis. On exam, he exhibited mild left upper quadrant and epigastric tenderness without evidence of peritonitis. CT imaging demonstrated splenomegaly with a large splenic hematoma measuring 15.7 × 9.2 × 12 cm and associated hemoperitoneum (Figs 1–3). In addition, innumerable osseous lytic lesions were identified. Given these findings, emergent surgical consultation was obtained and his coagulopathy reversed. He remained hypotensive despite resuscitation, thus was taken for laparotomy. Upon abdominal entry, a large amount of old clot was evacuated. The abdomen was packed in all quadrants in the standard fashion. Upon removal of the left upper quadrant packs, active hemorrhage began to well from the region of the spleen which was mobilized and removed via splenectomy. Upon gross inspection, the spleen was hyperemic and abnormally indurated, with an avulsion type injury extending several centimeters across the inferior pole. There was no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or other gross pathology. Given the patient was mildly hypothermic and coagulopathic with continued oozing from the retroperitoneum, the decision was made to pack the splenic fossa and place a temporary wound vac. The patient was transported to the ICU for resuscitation and brought back to the OR the next morning for re-exploration and closure. Despite hemodynamic stabilization, he underwent a prolonged hospitalization complicated by atrial fibrillation, renal allograft failure, VAP, and ultimately PEA arrest progressing to asystole. He died 6 weeks following splenectomy. The pathology from the spleen revealed splenomegaly with parenchyma that was replaced with amorphous and acellular eosinophilic material. Histologic staining (Thioflavin-T) was positive for amyloidosis, AL-type. Oncology was consulted based on these findings with concern for lymphoproliferative disorder given osseous findings on CT, splenic pathology, and history of immunosuppression. Bone marrow biopsy was subsequently obtained which showed more than 50% atypical plasma cells/plasma blasts (CD138+; PAX5 negative; EBV (EBER) negative) and no amyloidosis, consistent with multiple myeloma. Urine showed Bence-Jones protein. Serum immunofixation studies were remarkable for a monoclonal IgG lambda gammopathy, consistent with the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis associated with systemic myeloma.

Axial CT imaging showing hemoperitoneum secondary to splenic rupture.

Coronal CT imaging demonstrating splenomegaly with splenic capsule rupture at the inferior pole with heterogeneous fluid in the paracolic gutters and perisplenic region suggestive of hemoperitoneum.

Axial CT imaging of the pelvis demonstrating heterogeneous fluid (blood) in the pelvic small bowel mesentery. Also shown is the patient’s renal transplant with clear perinephric fat planes. The renal graft was grossly uninvolved and viable appearing at the time of laparotomy.

DISCUSSION

The most common etiology of splenic rupture in the absence of trauma remains hematologic processes, usually of malignant origin [1]. Retrospective studies have shown that various hematologic malignancies (30.3%), infectious conditions like EBV/HIV/malaria (27.3%), inflammatory states not related to infection (20.0%), drug/treatment-induced rupture (9.2%) and mechanical factors (6.8%) comprise about 93.6% of all cases, while no identified causal factors are isolated 6.4% of the time [4, 5].

Amyloid infiltration of the splenic parenchyma is one hematologic cause of spontaneous rupture. Amyloidosis is a generic term referring to the abnormal extracellular deposition of abnormally folded serum protein, termed fibrils. While over 20 serum proteins have been implicated in the formation of amyloid fibrils, the most common type is immunoglobulin or light chain (AL) amyloidosis, which represents a clonal disorder of plasma cells. In a retrospective review of 334 patients with AL amyloidosis, abnormal bleeding tendencies and abnormal coagulation studies were identified in 28 and 51% of cases respectively [6].

Diagnosis of AL amyloidosis often begins with biopsy of a less invasive surrogate site or an involved organ for histologic examination. Tissue specimens are then typically processed with Congo red stain, which produces apple green birefringence with binding to amyloid fibrils under polarized light, yellow-green fluorescence with Thioflavin-T stain, or 10-nm wide fibril aggregates on light microscopy [2, 7]. Once fibrils are identified, immunohistochemical staining is commonly employed to determine the specific type of amyloidosis. The final diagnostic criterion for AL amyloidosis is identification of a monoclonal and proliferative plasma cell disorder, detected either by an abnormal serum light chain ratio, the presence of a monoclonal protein (M) on serum/urine electrophoresis or serum immunofixation, or bone marrow biopsy demonstrating clonal plasma cells [8]. Our patient was found to have greater than 50% atypical plasmacyte/plasma blast ratio on bone marrow cytology, a monoclonal lambda IgG gammopathy on immunofixation, and multiple diffuse osseous lytic lesions, which is diagnostic for multiple myeloma.

It is established that the use of chronic immunosuppression following allogenic solid organ transplantation is associated with an increased risk of malignancy and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). The origin of PTLD is most often host-related and approximately 80% of cases occur within the first 12 months following transplant [9]. The overall risk of PTLD development has been well correlated with the degree of T-cell immunosuppression, age of the patient, and EBV serostatus (70% EBV+). In our patient, an aggressive EBV-negative monomorphic PTLD was diagnosed. Ultimately, the patient succumbed to multi-system organ failure secondary to septic shock.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- amyloid

- amyloidosis

- warfarin

- renal transplantation

- hypotension

- abdominal pain

- kidney failure, chronic

- antigens, cd98 light chains

- asthenia

- hemoperitoneum

- living donors

- pathologic processes

- rupture

- splenectomy

- splenic rupture

- splenomegaly

- wounds and injuries

- therapeutic immunosuppression

- natural immunosuppression

- multiple myeloma

- pathology

- spleen

- primary amyloidosis

- plasma cell disorder

- posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder

- bone marrow biopsy

- immunoglobulin deposition disease

- laparotomy, exploratory

- lytic lesion