-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John D L Brookes, Charlene P Munasinghe, Daniel Croagh, Jacob G Goldstein, Approach to a large rare diaphragmatic hernia in a patient undergoing cardiac surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 2, February 2019, rjz038, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hernia of Morgagni is an unusual congenital defect of the sternal portion of the diaphragm. Its concurrence with cardiac surgical pathology is rarely described in the literature. Notwithstanding, huge hernia of Morgagni have been noted to cause serious peri-operative impediment and complications. We report the case of a 50-year-old gentleman with a massive Morgagni hernia that threatened strangulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. We describe the combined surgical approach undertaken to repair this hernia, with an accompanying review of the literature relating to misadventure and management of similar large hernia coinciding with cardiac surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Large hernia of Morgagni concurrent to cardiac surgery has rarely been described, but has been noted to cause serious peri-operative impediment and complications. We report the case of a 50-year-old gentleman with a sizeable Morgagni hernia that threatened strangulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. We describe the combined surgical approach undertaken to repair this hernia, with an accompanying review of the literature relating to misadventure and management of similar large hernia coinciding with cardiac surgery.

CASE

A 50-year-old male presented with anterior STEMI manifesting as chest pain and dyspnoea while completing a treadmill stress echocardiogram. His cardiovascular risk factors were hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, smoking, obesity and a strong family history.

He underwent emergent coronary angiography that revealed triple vessel disease with moderate impairment of LV contractility. There was chronic occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery and the culprit lesion was an acute subtotal occlusion of the proximal left circumflex. He underwent stenting of the left circumflex and was referred for coronary artery bypass grafting of his residual disease.

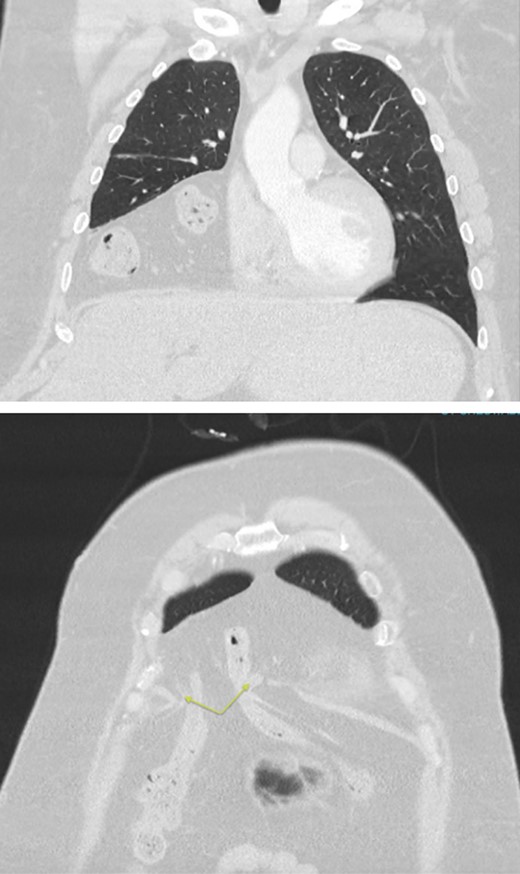

A chest x-ray and subsequent CT showed a large right anterior diaphragmatic hernia through the foramen of Morgagni, with colon in the chest, occupying about two-thirds of the pleural space (Fig. 1). Radiologically the defect measured 39 mm in AP dimension and 38 mm transverse. As the patient was asymptomatic from the hernia, the decision was made to undertake the hernia repair electively at a later time.

CT chest/abdomen/pelvis with large volume Morgagni hernia containing loops of bowel in the right hemithorax. Arrows highlighting the diaphragmatic defect.

Total arterial revascularization was undertaken with LITA-LAD, RA-OM1-OM2 and free RITA-AM-PDA. Intraoperatively, the patient required low dose adrenaline, noradrenaline and levosimendan prior to and during cardiopulmonary bypass. He was weaned without difficulty, but still requiring adrenaline and noradrenaline infusions.

The right chest cavity was almost completely replaced by abdominal contents, mainly colon, passing through a large anterior diaphragmatic hernia situated close to the midline and extending 10 cm to the right-side. The contents of the hernia became extremely tense during bypass, and the transverse colon was in danger of strangulation, risking post-operative obstruction. Therefore we decided to undertake concomitant repair of the hernia. The sternotomy wound was extended inferiorly through the linea alba and the hernia neck was incised. There was large volume haemoserous fluid and dense adhesions within the sac, which had to be divided to allow the contents to be reduced. The omentum was partially excised to ensure haemostasis and the sac was excised. There was no firm anterior border thus the diaphragmatic defect was closed with interrupted 1 nylon, rather than mesh, and the abdominal wall was closed with interrupted 1-nylon figure-of-eight sutures.

Post-operative recovery was uneventful, with the patient extubated Day 1, no features of ileus, and discharged home Day 7. He represented with superficial dehiscence of the inferior 12 cm of wound. This required debridement in theatre, and was allowed to heal by secondary intention.

DISCUSSION

Morgagni hernia arises from a congenital defect of the sternocostal portion of the diaphragm. It occurs due to lack of fusion of the pars sternalis and pars costalis during diaphragmatic development. It is an uncommon condition, accounting for 3% of all diaphragmatic hernias [1]. A systematic review by Horton found that 28% of patients were asymptomatic, while 72% had symptoms related to the hernia [2]. These included pulmonary symptoms, pain, obstruction, dysphagia, bleeding and reflux. The most common contents of the hernia sac are omentum and colon, although stomach, small bowel and liver can also be found.

Where Morgagni hernias are repaired in isolation, there is an increasing tendency for laparoscopic repair, although laparotomy accounts for 30% of repairs and thoracotomy for 49% [2]. In patients with concurrent cardiac disease requiring intervention, some surgeons advocate delayed repair of the hernia after cardiac surgery, although combined procedures have been performed with satisfactory outcomes [3].

The repair of diaphragmatic hernias at the time of cardiac surgery is rarely described in the literature with only a few case reports. The majority detail paediatric cases. The incidence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is 0.02–0.05%, and these can be repaired at the time of surgery for congenital cardiac defects [4].

Gopalakrishnan described a large midline defect with hernia contents in the pericardium found during emergent coronary revascularisation. This was repaired with prolene mesh prior to coronary revascularisation [5]. In a second case, of large Morgagni hernia displacing the heart and great vessels, Ahmad prepared the patient for concomitant repair with preoperative bowel prep and NG decompression of the stomach. The hernia sac was dissected from the underside of the sternum, and an oscillating saw used for sternotomy to minimize the risk of bowel injury [6].

Two case reports describe peri-operative difficulties due to diaphragmatic hernias in patients having cardiac surgery. Hasegawa described a Type A dissection repair where the patient was unable to be weaned off bypass due to extrapericardial compression of the heart from an incarcerated hiatal hernia [7]. Devbhandari reported haemodynamic instability postoperatively in a patient undergoing coronary bypass. This was attributed to a large oesophageal hernia, and resolved once the stomach was decompressed with a nasogastric tube [8].

Giuricin described a delayed case of incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia 5 months after cardiac surgery, which was not identified at the time of the primary procedure [9]. This required reoperation to reduce and repair the hernia.

Gastrointestinal complications occur in 0.3–3% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, with a wide variation in severity. Post-operative ileus now represents the most frequent gastrointestinal complication [10]. There is an association with cardiopulmonary bypass leading to post-operative ileus, and this risk is probably increased in patients who already have pre-existing bowel pathology including significant hernias. Although our patient had no symptoms from his hernia preoperatively to warrant emergent repair, intraoperatively the patient developed congestion of the bowel, risking strangulation. We hypothesize that this occurred due to cardiopulmonary bypass leading to tissue oedema, altered perfusion pressures, systemic inflammatory response and third-spacing of fluid.

Due to the risk of peri-operative complications with cardiac surgery, we propose that contents of hernias should be carefully inspected following cardiopulmonary bypass, and consideration should be given to concurrent repair of large diaphragmatic hernias, even in those patients who have no preoperative symptoms.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

The patient provided informed consent for publication of case and use of anonymized images.