-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Haley Prough, Sarah Jaffe, Brian Jones, Jejunal diverticulitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 1, January 2019, rjz005, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cases of small bowel diverticulitis, excluding Meckel’s diverticulitis, are rare. Small bowel diverticular disease has been reported in approximately 0.3–1.3% cases of post mortem studies (Fisher JK, Fortin D. Partial small bowel obstruction secondary to ileal diverticulitis. Radiology 1977;122:321–322.) and in only 0.5–1.9% of contrast media study cases (Cattell RB, Mudge TJ. The surgical significance of duodenal diverticula. N Engl J Med 1952;246:317–324). Diverticula located within the small bowel may have presentations and complications similar to that of colonic diverticular disease. However, there is no consensus for the management for small bowel diverticulitis. Given that small bowel diverticulitis, like a colonic diverticulitis, can cause an acute abdomen, surgical intervention may be required. In this particular case, a patient presented with symptoms of lower abdominal pain, nausea and fever. Following an x-ray and CT scan, the patient underwent an open laparotomy and small bowel resection of a portion of jejunum that contained a symptomatic diverticulum.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of small bowel diverticulitis is small; prevalence increases with age, characteristically in males in the sixth to eighth decades of life [3, 4]. Jejunal diverticula are thought to be pulsion diverticula secondary to intestinal dyskinesia [3]. Although jejunal diverticula are not an unusual finding within themselves, they create a nidus for possible complications including perforation, bleeding, abscess and obstruction [4]. The effects of these possible outcomes may lead to clinically confusing presentations, such as iron deficiency anemia due to diverticular bleeding [5]. These complications are rare but can be serious and potentially require surgical management in some cases. Therefore, it is imperative for providers to consider small bowel diverticula when managing any patient presenting with symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea and fever. There is little literature providing research on the presentation or management of small bowel diverticulitis, increasing the risk of the underlying pathology of patients with such symptoms being undetected. Small bowel diverticulitis, while rare, is a complication that must be addressed by providers to prevent significant morbidly and mortality in these patients.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old male with a history of Barrett’s esophagus presented to the emergency department with acute pain across his lower abdomen, nausea and fever of 39.4°C. The lower abdominal pain was described as sharp and most notably in the left lower quadrant. On physical exam, the pain was present upon palpation of the abdomen, but no guarding or rebound was noted. Bowel sounds were normal and abdominal distension was noted. The patient stated that he had never experienced symptoms similar to these previously.

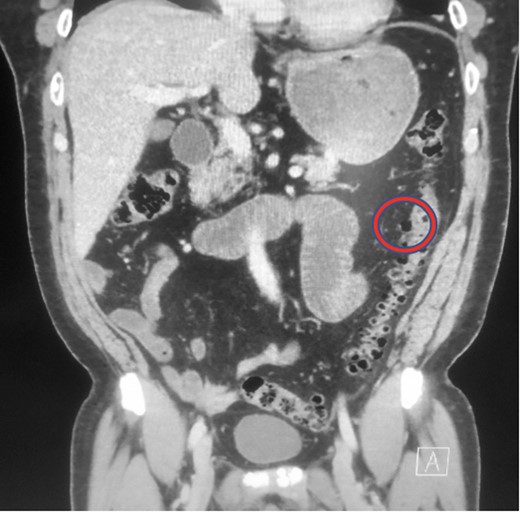

The patient’s WBC count was 15.10 k/μL (3.80–10.80 k/μL) and all other laboratory data was within normal limits. A chest x-ray was unrevealing. An abdominal and pelvis CT with IV contrast revealed a small collection of air and debris adjacent to a loop of mildly thick-walled small bowel in the left lower quadrant measuring roughly 2.3 × 1.9 × 2.0 cm3, with a small adjacent focus of apparent extraluminal air (Fig. 1). The CT also did reveal extensive colonic diverticulosis; however, the radiographic evidence was suggestive of the possible sequelae of an acute perforated small bowel diverticulitis as opposed to a perforated colonic diverticulitis.

Abdominal CT demonstrating collection of air and debris. Area of interest is circled in red.

The patient was medically treated with ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 h), metronidazole (500 mg IV every 8 h), ondansetron (4 mg every 6 h, PRN) and pantoprazole (40 mg IV daily).

Following a surgical consult with the patient and his family, it was decided to pursue surgical treatment with an open laparotomy with possible small bowel resection. The operation was performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal, nasogastric (previously placed) and Foley catheter intubation. The abdomen was widely shaved, prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. A midline incision was made from above the umbilicus to just below the umbilicus through a previous supraumbilical scar from his prostatectomy, and subcutaneous tissue was dissected with cautery and fascia was opened under direct visualization along with the peritoneum sharply. Exploration was done manually and visual for the entirety of the abdominal cavity.

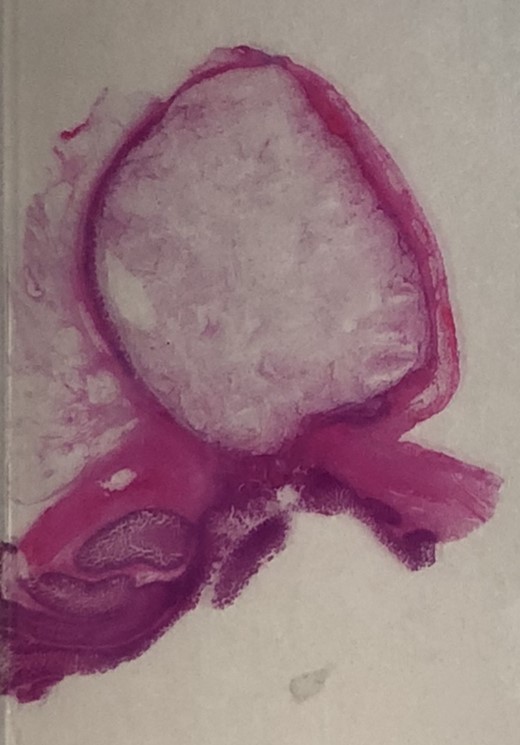

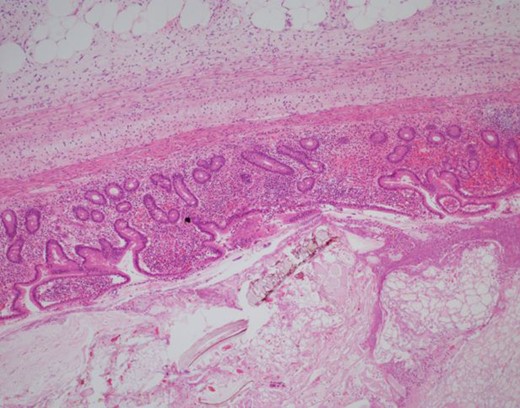

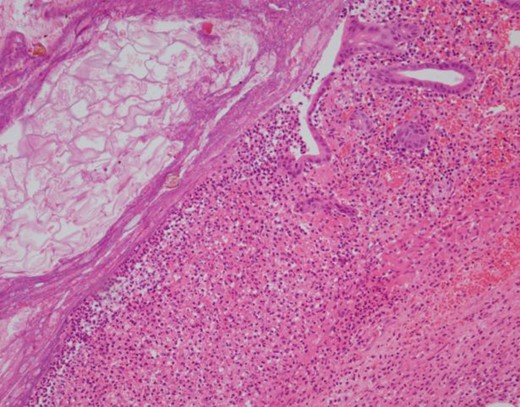

During the exploratory laparotomy, the segment of small bowel with the inflammatory phlegmon was noted and withdrawn from the surgical site for inspection. An isolated segment of bowel measuring ~20 cm was resected between and a side-to-side functional and end anastomosis was created. The surgical findings included a solitary diverticulum at the mesenteric aspect of the bowel with marked erythema, induration and slight exudate at the proximal jejunum. There was no evidence of diverticular perforation. Pathology revealed the serosal surface of the jejunum was notable for a 2.5 cm region of protrusion associated with congestion, exudation and possible hemorrhage; when the resected segment of small bowel was opened, there was a prominent fecal filled diverticulum corresponding to the focus of serosal protrusion (Figs 2–4).

H&E 1× image of the small bowel diverticulum (top of image) pouching out from the bowel lumen (bottom of image).

H&E 40× image of the mucosal lining of the diverticulum and ingested food debris in the lumen. Only the mucosa is present in the wall, which classifies this as an acquired rather than congenital.

H&E 100× image demonstrating an area of ulceration in the diverticulum with fibrinopurulent exudates occupying most of the right side of the image and food debris in the lumen at the upper left.

The patient had an unremarkable recovery with no complications for the remainder of his admission. The patient was discharged home 5 days after surgery when ambulating, having bowel function, tolerating diet.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of small bowel diverticulitis in a 65-year-old male who presented with abdominal pain, nausea and fever. Initial medical management was utilized to stabilize the patient, and surgical management was then pursued. In this case, surgical management of small bowel diverticulitis was successful in this patient. The success of this method could likely be replicated in other patients with similar presentations and pathologies. However, there is a lack of research of the efficacy of medical management compared to surgical management of this condition, which leaves the provider to decide between the two interventions.

In cases of diverticular bleeding, there is an indication for surgical management to remove the affected area of small bowel [5]. The area is first localized via intraoperative endoscopy or CT angiography. Failure to satisfactorily remove the region of bleeding could expose the patient to complications including anemia and shock. In this situation, surgical management is more clearly chosen. In patients without acute bleeding from a diverticulum, the choice may be less clear on how to proceed with treatment. Both medical and surgical management options offer potential solutions, and each is with risks and benefits. When proposing a surgical intervention, a patient’s overall health status and personal medical history must be considered.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- diagnostic radiologic examination

- acute abdomen

- small bowel obstruction

- computed tomography

- contrast media

- colonic diverticulitis

- diverticular disease of colon

- fever

- diverticulitis

- diverticulum

- intestine, small

- laparotomy

- nausea

- surgical procedures, operative

- ileum

- jejunum

- meckel's diverticulum

- small-intestine resection

- diverticulum of duodenum

- abdominal pain, lower

- consensus

- diverticular diseases