-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stephanie Taha-Mehlitz, Julia Bockmeyer, Elza Memeti, Miriam Nowack, Jürg Metzger, Jörn-Markus Gass, Mantle cell lymphoma—rare differential diagnosis of a tumor in the vermiform appendix, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 1, January 2019, rjy367, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy367

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although the most common localization of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the gastrointestinal system, the infiltration of the vermiform appendix is a very rare condition. We report a case of mantle cell lymphoma affecting the appendix as an incidental finding due to gynecological surgery. A 57-year-old woman presented with increasing pain in the right lower abdomen since months. During gynecological evaluation an inhomogenous mass in the right ovarian place was noticed and misinterpreted as ovarian tumor. Laparoscopic ovarectomy was planned. The intraoperative situs showed surprisingly a massive enlarged appendix and completely normal ovaries. Since the lesion was suspicious for appendiceal cancer, a right hemicolectomy was performed. Histopathology revealed a non-Hodgkin lymphoma with immunohistochemical proof of blastoid B-cells, a mantle cell lymphoma. Polychemotherapy was administered.

INTRODUCTION

At least one-third of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas appear in the gastrointestinal system, for mantle cell lymphomas (MCL) the amount is ~25% [1, 2].

Whereas the colon is the most common site of gastrointestinal MCL, presenting with polypoid lesions, the appendix is rarely affected, usually by ingrowing of ileocecal region [3].

Different clinical appearance and non-specific symptoms may cause delayed diagnosis.

We report a case of a female patient complaining non-specific increasing pain in the right hemiabdomen. The patient was first assessed by the gynecologists. Then laparoscopy revealed a surprising diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old woman presented with diffuse abdominal pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant since several months. The pain was increasing while sitting, she also suffered from hot flushes and diarrhea. Weight loss, night sweats or fever were not documented.

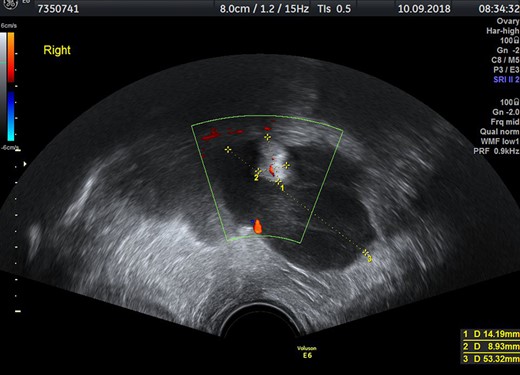

First seen by gynecologists, endovaginal ultrasound showed a solid tumor measuring 10×5×6.5 cm3, with inhomogeneous structure, suspicious of ovarian tumor (Fig. 1). Tumor markers for ovarian carcinoma were inconspicuous, only the CA 125 was slightly elevated (49.2 U/ml, reference <35 U/ml). A diagnostic laparoscopy and ovarectomy were planned.

Transvaginal ultrasound with inhomogenous mass in the right part of the small pelvis.

The diagnostic laparoscopy revealed a strongly thickened and hardened vermiform appendix with a slightly porcelain-like surface and the appendiceal basis was involved (Fig. 2). In addition, massive mesenterial and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy as well as peritoneal nodules especially in the small pelvis and right lower abdomen were detected (Fig. 3). Since low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) or neuroendocrine tumor were possible differential diagnosis, a midline laparotomy and right-sided hemicolectomy with oncological central lymph node resection was performed. Bowel continuity was restored by a side-to-side anastomosis of the terminal ileum and the transverse colon in hand-sewn technique. Frozen section showed infiltrations of lymphoma.

Thickened appendix and mesoappendix with porcelain-like suface.

The postoperative course and recovery were uneventful. The patient was discharged 11 days after surgery.

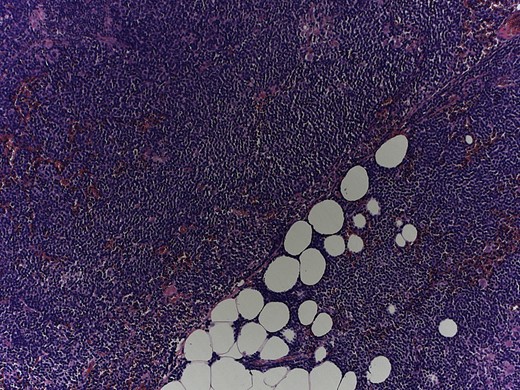

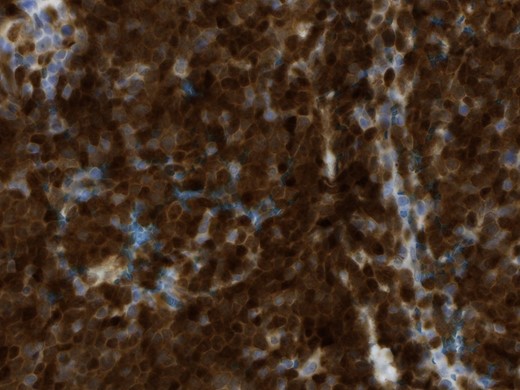

In the pathological assessment the appendix measured 10 and 4.5 cm in diameter. Histopathology revealed an infiltrating non-Hodgkin lymphoma, blastoid B-cell-type, a mantle cell lymphoma. The immunohistochemical pattern was positive for CD20, CD5, Cyclin D1, bcl-6 (that fits for blastoid type), negative for CD3, CD23 and CD10. MIB-1 was up to 75% (Figs 4 and 5).

Magnification 10×, hematoxylin and eosin staining shows a monomorphic lymphoid population with a diffuse growth pattern.

Magnification 40×, the immunohistochemical staining shows strong diffuse nuclear expression of Cyclin D1 (>95% of all mantle cell lymphoma including CD5-negative cases).

Staging was completed with positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan and bone marrow biopsy. Since there were suspicious lymph nodes supra- and infradiaphragmal and no splenomegaly, Ann Arbor Stage IIIA resulted.

Polychemotherapy was conducted within a study protocol afterwards.

DISCUSSION

The MCL accounts for 4–9% of all lymphomas. A chromosomal translocation between chromosome 14 and the Cyclin D1 gene on chromosome 11 is pathognomic. The t(11;14)(q13;q32) leads to overexpression of Cyclin D1 and activation of the cell cycle. Immunohistochemical detection of Cyclin D1 or the proof of translocation in fluorescence in situ hybridization is necessary to differentiate from other lymphomas. Extranodal manifestations (e.g. intestinal manifestation) are more frequent than in other lymphomas [4]. The appendix is usually involved by infiltration of ileocecal MCLs per continuity [3].

Appendical lymphomas, with an incidence assumed to be <2% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas, are described to affect typically male patients with median age of 53 years and white race [5–7]. Extranodal lymphomas occur more often in immunocompromised patients, like post-transplant immunosuppressants or those with immunodeficiency syndromes [8].

Clinical findings are very variable. Incidental findings with thickened appendix without any symptoms, as well as a history of abdominal pain, often in the right lower quadrant, fever, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting or gastrointestinal bleeding can be present. Even acute appendicitis due to luminal obstruction is described [7, 9]. One-third of patients with MCL present with systemic B symptoms.

Besides unspecific symptoms there are no typical diagnostical and radiological signs. Suspect ultrasound findings of the appendix should be evaluated by CT scan in order to be able to determine a surgical strategy preoperatively. In the CT scan diffuse mural soft-tissue thickening with diameter ~2.5 cm or more and simultaneously abdominal lymphadenopathy may rise the suspicion of appendiceal lymphoma, but there are no pathognomonic patterns [6, 7]. Therefore, the diagnosis is usually confirmed histopathologically.

Because of its rarity surgical management of lymphoma affecting the appendix is based on published case reports and case series. There are no clear guidelines for therapeutic treatment. Usually, an appendectomy or right hemicolectomy is performed. Although there seems to be no survival benefit for hemicolectomy in comparison with a single appendectomy. In our case the basis of the appendix was thickened and infiltrated too, therefore, right hemicolectomy was performed. Surgery is followed by adjuvant polychemotherapy and allogenic stem cell transplantation if necessary, depending on stage and histopathological result [5].

In addition to the extent of the surgery, it must also be taken into account that chemotherapy cannot be started immediately after major surgical interventions. It remains unclear if such a delay has an impact on long-term prognosis. After treatment, a close surveillance is recommended.

In a cohort of 116 patients the mean overall survival for patients with lymphoma of the vermiform appendix was 185 months and the 5-year survival rate was 67% [5].

Regarding mantle cell lymphoma, the proliferation index Ki67 and its antibody MIB-1 as histopathological parameters have a high prognostic relevance. In addition, clinical aspects as well as the patient’s general condition may help to estimate prognosis in the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index [10].

CONCLUSION

We described a rare case of mantle cell lymphoma involving the vermiform appendix misinterpreted as ovarian disease.

Infiltrating mantle cell lymphoma causing appendiceal tumor is a rare differential diagnosis of right lower abdominal pain and should always be considered preoperatively, especially in cases of conspicuous imaging.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the patient who has provided written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest statement

None declared.

REFERENCES

- combination drug therapy

- b-lymphocytes

- differential diagnosis

- gastrointestinal system

- gynecologic surgical procedures

- intraoperative care

- laparoscopy

- mantle-cell lymphoma

- lymphoma, non-hodgkin

- ovarian neoplasms

- pain

- abdomen

- neoplasms

- ovary

- colectomy, right

- malignant neoplasm of appendix

- histopathology tests

- incidental findings

- extranodal disease