-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kazuki Hayashi, Jun Hanaoka, Yasuhiko Ohshio, Tomoyuki Igarashi, Chylothorax secondary to a pleuroperitoneal communication and chylous ascites after pancreatic resection, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 1, January 2019, rjy364, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy364

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previous reports of chylothorax developing after pancreatectomy, although chylous ascites can occur. In patients with a pleuroperitoneal communication, ascitic fluid can flow into the thoracic cavity through a small hole in the diaphragm. A 70-year-old woman underwent total pancreatectomy and was referred to our department for treatment of right chylothorax after removal of her abdominal drainage tubes. An occult pleuroperitoneal communication was detected, and the portion of the diaphragm containing a diaphragmatic fistula was resected using a surgical stapler. After surgery, the chylothorax resolved, but chylous ascites developed. We speculated that this was a rare case of chylous ascites that flowed into the thoracic cavity through a diaphragmatic fistula after a pancreatic resection. When a patient develops chylothorax after an abdominal operation, the combination of a pleuroperitoneal communication and chylous ascites must be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Chylothorax is classified as traumatic or non-traumatic. Most cases of non-traumatic chylothorax develop in childhood. Chylous ascites results from either traumatic or non-traumatic events and affects ~1.3% of patients after pancreatic resection [1]. In patients with pleuroperitoneal communications, ascites flows into the thoracic cavity through small holes in the diaphragm. Such communications have been reported in 1–2% of peritoneal dialysis patients [2], but they primarily result from congenital abnormalities. Herein, we present a rare case of chylothorax initially thought to be from an unknown cause; however, considering the patient’s history of pancreatectomy and subsequent clinical course, we determined that her chylothorax resulted from chylous ascites that flowed through a pleuroperitoneal communication after pancreatectomy.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old woman underwent total pancreatectomy for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia. Her abdominal drainage tubes were removed on postoperative Days 7 and 8. The ascites volume at that time was not small, but the gastrointestinal surgeons’ policy was to control ascites with diuretics as opposed to drainage; thus, the abdominal drainage tubes were removed. The ascitic fluid was not sent for a biochemical examination. On postoperative Day 12, a chest radiograph showed an acute development of right hydrothorax (Fig. 1). Thoracentesis was performed on postoperative Days 12 and 23. On postoperative Day 23, the pleural fluid was sent for biochemical analysis for the first time. The results showed elevated triglyceride levels (536 mg/dL) and the patient was diagnosed with a right chylothorax. At that time, she had no abdominal symptoms or obvious ascites. After a 1-month long fat-restricted diet and octreotide treatment, the chylothorax was not substantially improved and she was referred to our department.

Chest radiograph on postoperative Day 12 after pancreatectomy A chest radiograph showing a right-sided sub-massive pleural effusion.

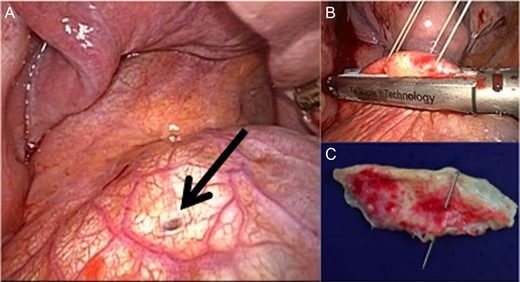

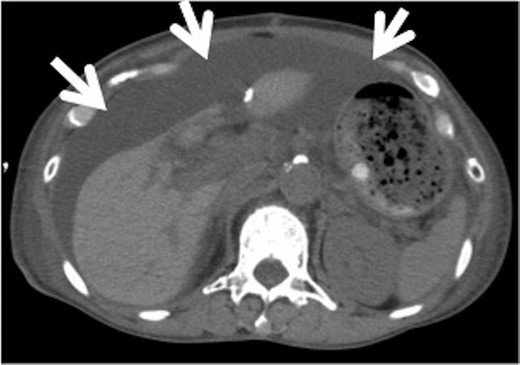

We considered it unlikely that the intrathoracic segment of the thoracic duct was damaged during the previous surgery because there was no documentation of intraoperative diaphragmatic injury, which can often occur in oesophageal cancer operations. We believed the chylothorax occurred regardless of the abdominal surgery. We planned to examine the thoracic cavity and ligate the thoracic duct during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Intraoperatively, we detected a small fistula on the right hemidiaphragm and closed the fistula with partial resection of the diaphragm (Fig. 2A–C). We also ligated the thoracic duct as originally planned. The fistula appeared to be fibrotic; however, no other pathological abnormality was observed in the excised diaphragmatic tissue. Postoperatively, the patient resumed oral intake. The pleural effusion did not increase in volume and the pleural fluid triglyceride level was within normal limits (12 mg/dL). Nine days later, she reported a sensation of abdominal distension. An abdominal computed tomography revealed large ascites (Fig. 3). Abdominocentesis was performed, and the triglyceride level in the ascites was elevated (124 mg/dL). She was diagnosed with chylous ascites. By maintaining the abdominal cavity drainage, discontinuing oral intake and continuing octreotide administration for 3 weeks, the chylous ascites gradually improved.

Operative findings during thoracic surgery. (A) Operative findings show a diaphragmatic fistula (arrow). (B) The fistula is closed with a surgical stapler. (C) The resected diaphragm shows a pleuroperitoneal communication. (Fibrosis was observed; however, no other pathological abnormality was identified in the excised diaphragmatic tissue.)

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) after thoracic surgery. Abdominal CT after thoracic surgery shows sub-massive ascites (arrows).

DISCUSSION

We present the unique case of a patient who developed chylothorax followed by chylous ascites after pancreatectomy, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first reported case of post-pancreatectomy chylothorax.

Pleuroperitoneal communications occur with diaphragmatic fistulae. Ascites or dialysate flowing from the abdomen to the thoracic cavity occurs primarily because of negative pressure in the pleural cavity. Pleuroperitoneal communications develop in 1–2% of patients treated with peritoneal dialysis [2]. Although the most common aetiology of a pleuroperitoneal communication is a congenital diaphragmatic defect, it can also arise through an anatomical hiatus, such as the oesophageal hiatus, or rupture of a fragile part of the diaphragm secondary to increased intra-abdominal pressure. In some cases, the weakened diaphragmatic segment cannot be identified [3]. In the present case, we identified a small fistula on the diaphragm that was not located at a site involved with the previous pancreatectomy. Because no diaphragmatic injury occurred during the prior abdominal surgery, we considered that the fistula was present before surgery. Reportedly, small defects may exist in an otherwise normal diaphragm [4].

Chylous ascites is caused by intra-abdominal leakage of lymphatic fluid containing triglycerides. The aetiologies of chylous ascites include lymphatic fluid stasis resulting from infiltration of malignancies or tuberculosis, surgery and trauma. Assumpcao et al. [1] reported that 1.3% of pancreatectomies were complicated by chylous ascites. A diagnosis of chylous ascites can be confirmed when peritoneal cavity fluid has a triglyceride level of >110 mg/dL. Conservative therapies for chylous ascites include institution of a low-fat diet, fasting and administration of octreotide. Surgical treatments for chylous ascites include intra-abdominal dissemination of fibrin glue [5] ligation of the lymphatic duct injury site, or placement of a peritoneovenous shunt [6]. Chylothorax is caused by leakage and accumulation of lymph. Its aetiology, diagnosis and treatment are similar to those of chylous ascites.

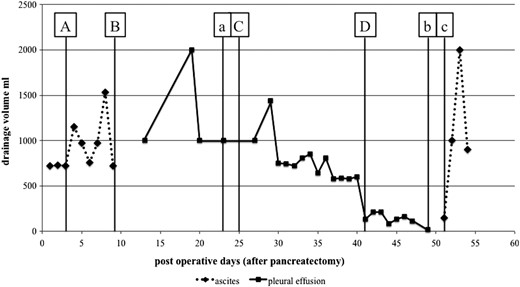

In the present case, the aetiology of the chylothorax was not initially clear because the likelihood that the diaphragm and the thoracic duct in the thoracic cavity were damaged during the pancreatectomy was low. The patient’s clinical course had two stages. First, she underwent total pancreatectomy and developed chylothorax after removal of the abdominal drainage tubes. Second, after surgical closure of the diaphragmatic fistula, her chylothorax was cured, but then she developed chylous ascites (Fig. 4). This clinical course suggests that her condition resulted from a combination of chylous ascites after her abdominal surgery and a pleuroperitoneal communication. Although the thoracic duct ligation and the onset of chylous ascites occurred contemporaneously, no previous reports have described this phenomenon after thoracic duct ligation, which is a widely accepted practice in the treatment of chylothorax. Although a limitation of this study is that the location of chyle leakage had not been identified, for example, via lymphangiography with lipiodol [7], it is reasonable to conclude, based on the clinical course described so far, that the leakage point was in the abdominal cavity. Fortunately, this patient’s chylous ascites resolved with conservative management. Prolonged lymph leakage leads to undernutrition and decreased immune system function. Therefore, when chylothorax is discovered after abdominal surgery, especially pancreatectomy (although rare), the possibility of combined effects of chylous ascites and a pleuroperitoneal communication should be considered.

Clinical course and triglyceride levels of ascites and pleural effusion (A) After resuming oral intake, the amount of ascitic fluid increased. (B) After removal of the abdominal drainage tubes, a pleural effusion appeared. (C) The patient was treated with a low-fat diet followed by discontinuation of oral intake and administration of octreotide. More than 500 mL of pleural effusion was drained daily. (D) Following thoracic surgery, the patient developed abdominal ascites. (a) The triglyceride level in the pleural effusion is 536 mg/dL. (b) The triglyceride level in the pleural effusion is 12 mg/dL. (c) The triglyceride level in the ascitic fluid is 124 mg/dL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was approved by the local institutional and ethics review board. Because it was not a trial, consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this manuscript and all accompanying images.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.