-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eugene Wang, Ashley Humphries, Laura S Johnson, Small bowel obstruction due to internal hernia through sigmoid epiploica, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 1, January 2019, rjy342, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy342

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Internal hernia is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction; even more rare is one that occurs through a sigmoid epiploica defect. There have been only two previously reported cases from this etiology, but both were without the advantage of high-resolution imaging. We report the first color representation of this pathology, along with the first video recording of the internal hernia reduction. While this is a rare case, it is an important diagnosis to consider in the differential for patients presenting with a small bowel obstruction, with no previous abdominal surgeries or clinical findings of extra-abdominal hernias.

INTRODUCTION

Small bowel obstruction etiologies are classified into extrinsic (adhesions, hernia, volvulus), intrinsic (malignancy, strictures), and intraluminal (intussusception, gallstone ileus, bezoars). Extrinsic small bowel obstructions are the most common, and within this category, adhesive disease accounts for 74% of cases [1]. Hernias are the second most common extrinsic cause of small bowel obstruction, and hernias can be divided into extra-abdominal hernias (ventral and inguinal hernias being most common) and internal hernias, which are low in frequency. Internal hernias are further categorized into seven major types: paraduodenal (53%), pericecal (13%), Foramen of Winslow (8%), transmesenteric (8%), sigmoid mesocolon (6%), pelvic/supravesicular (6%) and transomental (4%) [2–4]. The other 2% of internal hernias are unclassified. We report a rare case of a small bowel obstruction due to internal herniation through a sigmoid colon epiploica defect, which belongs to this last group.

CASE REPORT

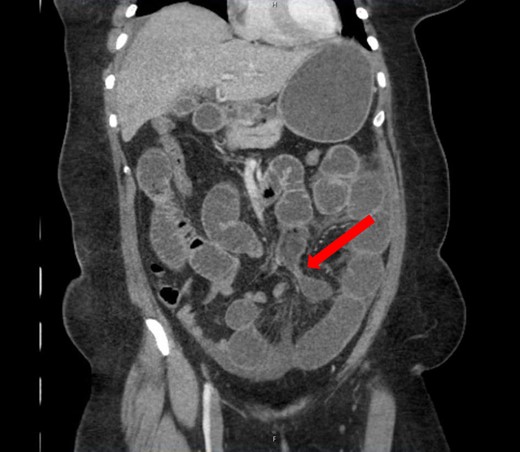

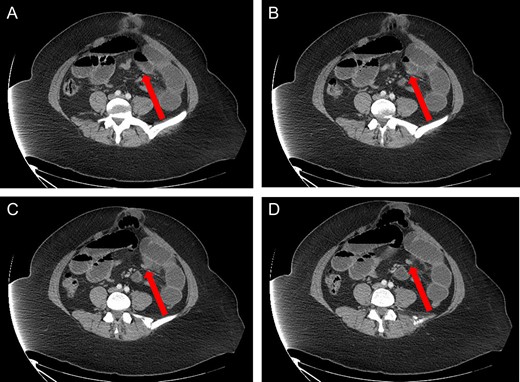

A 40-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain for 4 days. She had previously been seen at an outside hospital 3 days earlier, and was diagnosed with biliary colic. Her pain was constant, and was associated with nausea and vomiting. She had a history of a cesarean section, but no other abdominal surgeries. Her vitals were within normal limits: afebrile at 36.9°C, heart rate 71 beats/minute, blood pressure 143/62 mmHg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. On abdominal exam, she was distended, tender, demonstrated voluntary guarding and was positive for peritonitis. Laboratory values were significant for a white blood cell count of 16.1 K/ul, with 80.2% neutrophils, hemoglobin 14.9 g/dl, hematocrit 45.4%, platelets 349 K/ul and lactic acid 0.9 mEq/L; her chemistry was unremarkable. A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis that was obtained prior to surgical consultation demonstrated the proximal two-thirds of small bowel dilated up to 4 cm, with a sharp transition point in the left mid-abdomen, and collapsed small bowel loops near the cecum. The colon was mostly collapsed. A few distended loops bulged into a paraumbilical hernia, which was 6 cm wide and not the cause of obstruction (Figs 1–3).

Coronal view: arrow pointing to the dumb-bell transition point, where the proximal end of the closed loop small bowel herniated through a hole in the sigmoid epiploica.

Coronal view: arrow pointing to the sharp transition point, where the distal end of the closed loop small bowel herniated through a hole in the sigmoid epiploica, demonstrating collapsed small bowel distally.

Axial view: (A) and (B) arrows pointing to dilated small bowel from the closed loop obstruction. (C) and (D) arrows pointing to the transition point, where the small bowel is collapsed distally.

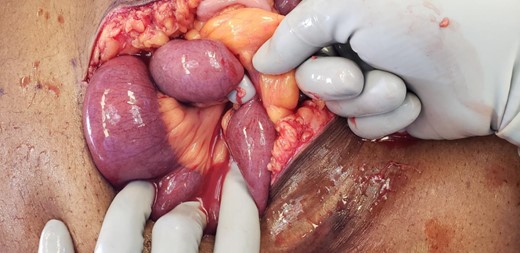

With these findings, we discussed with the patient an operative intervention for her pain, to which she agreed. Through a midline incision, we eviscerated the dilated small bowel, and found a 40 cm long segment of small bowel herniating through a 2 cm defect of a sigmoid colonic epiploica (Figs 4 and 5). We reduced the small bowel and saw two hyperemic markings corresponding to the points of incarceration along the bowel. The proximal point of incarceration demonstrated a dumb-bell shaped dilation of the small bowel. The distal point of incarceration had decompressed small bowel distally, and dilated small bowel within the closed loop aspect. The closed loop of small bowel was initially dark and congested, but immediately demonstrated healthy reperfusion after it was reduced. Because it was viable, no small bowel resection was performed. We used two Kelly clamps and 2-0 silk sutures to ligate and divide the sigmoid colon epiploica defect (Fig. 6). There were no other points of obstruction along the small bowel, and the abdomen was closed, repairing the umbilical hernia in the process. The patient was seen 1 month post-operatively and was doing well.

Intra-operative photo with index finger placed in the hole of the sigmoid epiploica, the site where small bowel is herniating through.

Intra-operative photo, second view, with index finger placed in the hole of the sigmoid epiploica, demonstrating the closed loop of small bowel.

Intra-operative photo, status-post reduction of internal hernia. The defect in the sigmoid epiploica is approximately 2 cm in diameter.

DISCUSSION

The first case of small bowel obstruction due to internal herniation through a colonic epiploica was described by Kringsman et al. in 1997 [5], in which a patient presented with obstructive symptoms without a surgical history, had leukocytosis, and an abdominal radiograph consistent with obstruction. The patient was found to have 30 cm of strangulated jejunum which required a small bowel resection. The second case, described by Liu et al. in 2004, likewise described a patient with obstructive symptoms in the absence of surgical history [1]. Similar to the previous case report, the patient had leukocytosis and a plain film consistent with obstruction. The patient was initially managed conservatively, but eventually required a laparotomy, during which they found 20 cm of distal ileum was found, without gangrenous change. Thus, only the epiploic fat foramen was excised.

Our patient again presented with obstructive symptoms and leukocytosis; however, unlike the previously reported cases, our patient did have prior abdominal surgery (cesarean section). After eliciting peritonitis on exam, and reviewing the dumb-bell shaped small bowel obstruction on CT, we immediately took the patient for a laparotomy. Interestingly, she did not have full thickness necrosis of her bowel despite the presence of peritonitis on exam; however, it was clear intra-operatively that her threatened bowel would have progressed to complete strangulation and bowel necrosis without emergent intervention.

While the era of never letting the sun set on a small bowel obstruction has passed, this case illustrates how multiple factors should be considered in the decision-making process for operative versus non-operative management in patients with small bowel obstruction [6]. For cases in which surgical decision-making is equivocal, it is important to create a complete differential diagnosis, from common causes such as adhesions and extra-abdominal hernias, to less common causes such as gallstone ileus and internal hernias. While our patient’s peritonitis on exam was a significant reason for urgent laparotomy, there were no intra-operative findings of an irritated peritoneum, such as succus, bile or full thickness bowel necrosis. Although we had the supportive findings of leukocytosis and a concerning dumb-bell shaped bowel obstruction on CT, it is conceivable that she could have presented without physical exam findings which could possibly lead to early conservative management rather than surgical intervention. While most adhesive small bowel obstructions are managed conservatively, particular consideration should be given towards operative management in patients with obstructive symptoms but without surgical history or extra-abdominal hernias, as closed loop small bowel obstructions from internal hernias can rapidly progress from incarceration to strangulation and full thickness bowel necrosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The views expressed within this paper are by the authors only, and not by Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

ETHICAL APPROVAL STATEMENT

For this type of retrospective case report; formal consent is not required.

INFORMED CONSENT STATEMENT

The pictures and video from this article submission are owned by the authors, and we give the journal permission for use in the event publication.

AUTHORSHIP

- LJ

Conception, design, overall responsibility;

- EW, AH

Data collection;

- EW

Analysis and interpretation of data;

- EW

Writing the article;

- LJ, AH

Critical revision of the article;

- LJ

Final approval of the article