-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Samer Alhames, Khaldoun Almhanna, Large rib osteochondroma in a child in Aleppo, Syria, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 9, September 2018, rjy247, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy247

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Osteochondromas are the most common tumors of the long bones in children. Osteochondromas can rarely be seen in the chest wall and they are usually diagnosed at a young age. They can be sporadic or part of the hereditary multiple exostoses.

We report a 12-year-old boy, who presented with a hard and large mass in the chest wall. The mass grew slowly after the original resection. Diagnosis and treatment were delayed because of the war. Radiological examination showed a large calcified tumor pushing the upper lung lobe. He was treated surgically. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of an osteochondroma with no evidence of malignancy.

Osteochondroma occur most frequently in long bones next to the metaphysic. These tumors can also develop in unusual sites. Wide total excision with negative margins is important to prevent recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Osteochondroma is the most common benign bone neoplasm in children [1], It is a cartilage-forming tumor that can be sporadic or part of the hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) [2, 3].

Osteochondroma presents at young age and commonly occur in the long bones. It usually presents as a painless mass; however, it can cause pain, deformity and even pathological fractures. Rib osteochondroma can cause pneumothorax and vertebral osteochondroma can cause spinal cord compression [4].

CASE REPORT

We report a case of a 12-year male with history of a small osteochondroma of the rib resected at age 5, who presented with a large anterior chest wall mass slowly progressing in the last 2 years. He failed to present to medical attention because of the war. Upon presentation, he was asymptomatic aside from the disfiguring effects of the mass (Fig. 1a). Family history was negative for multiple osteochondromas. Physical examination revealed a well-defined left chest wall mass ~17 × 17 cm2. The mass was hard, fixed, non-tender and did not adhere to the skin. There was no clinical evidence of HME.

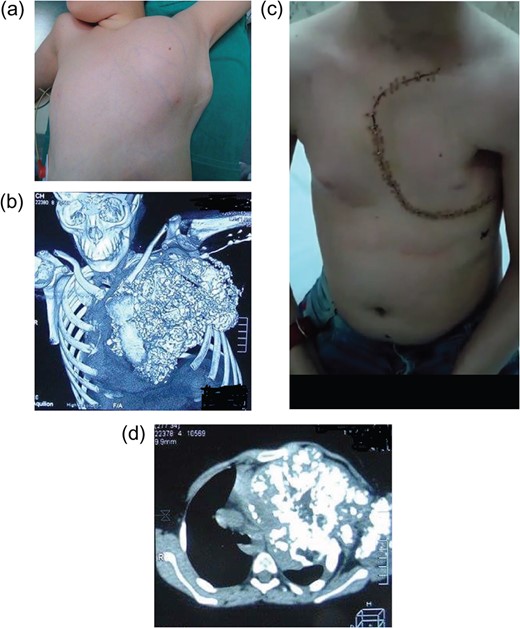

(a) A 12- year-old boy presented with a large chest wall mass, later diagnosed with osteochondroma. (b) 3D CT scans of the chest showing the large lobulated calcified mass. (c) Patient’s picture at follow up with no diformity and left anterolateral thoracotomy incision. (d) CT scans of the chest showing a large calcified mass extending from the upper chest to the left diaphragm.

Computed tomography of the chest (Fig. 1d) showed a large 17 × 17 cm2 mass arising from the anterior aspect of the first to fourth ribs. The exostoses protruded through the intercostal space with extensive calcification. The mass replaced the left upper lung lobe causing mediastinal shift with possible invasion. Three dimensional CT showed a large lobulated bony protrusion on the chest wall (Fig. 1b).

The patient was cleared for surgery. Under general anesthesia, left Trapdoor incision was performed [5], we prepared a musculocutaneous flap including the pectoralis major, the pectoralis minor and serratus anterior muscle. We performed a Left anterolateral thoracotomy at the level of fifth intercostal space, we disarticulated the clavicle at the level of the sternoclavicular joint, we then resected 1 cm of the left edge of the sternum after controlling the internal mammary pedicle along with the anterior two-third of the first four ribs after controlling the corresponding intercostal pedicles. Left upper lobectomy was indicated because of the concerns of tumor infiltration. The tumor then was resected en-block with the left upper lobe. The tumor impression on the diaphragm was also excised and sent for pathology. We reconstructed the chest wall using neo-rib technique.

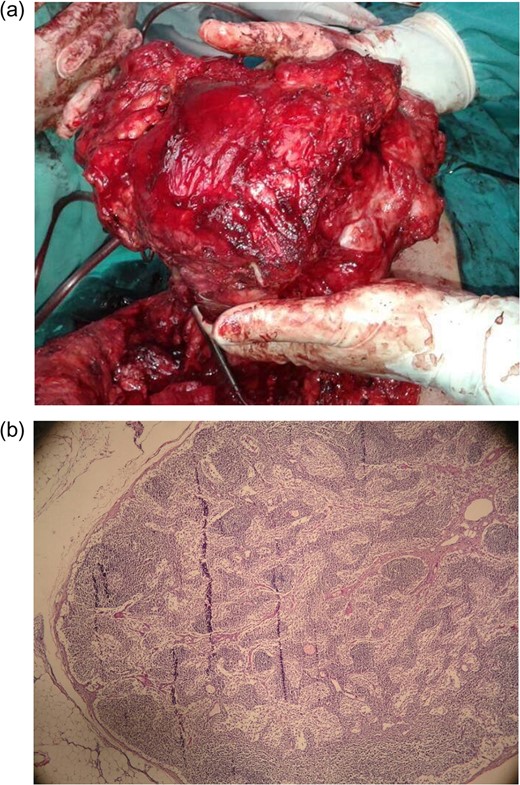

The gross specimen of the mass measured 16 × 19 × 21 cm3 and weight 2554 g (Fig. 2a). The mass included significant central cartilaginous material and calcification without invasion.

(a) A completely resected large osteochondroma measuring 17 × 17 cm2 with ribs and the left upper lobe. (b) Low power view of cartilaginous cap with chondrocytes are arranged in an orderly fashion.

Histologic examination confirmed a typical osteochondroma with a thin cartilage cap composed of monotonous proliferation of cartilage cells with no evidence of malignant transformation (Fig. 2b). In the deep aspect of the mass, the cartilage undergoes enchondral ossification, forming the inner portion of the head and stalk.

The patient was discharged in stable condition. On follow up, he recovered well (Fig. 1c). He presented with left shoulder weakness which thought to be secondary to axillary nerve injury from stretching during surgery. He was treated with low dose steroids and physical therapy with significant improvement. He has no recurrence on follow up.

CONCLUSION

Osteochondromas are the most common benign tumors of the bones with the incidence being 1 in 50 000 children. Costal osteochondromas are usually asymptomatic unless they became large causing pain, functional problems or deformities. Rarely, osteochondromas can lead to brachial plexopathy, hemothorax and pneumothorax. Malignant transformation has been reported as well can occur in 0.5–10% of patients with HME [3].

The diagnosis of costal osteochondroma is relatively easy. Plain X-ray is routinely used but CT or MRI is more sensitive in identifying geographic relationships with neighboring structures and helping with the surgical resection. MRI can help defining the thickness of the cartilage cap as well.

Treatment of osteochondroma is usually conservative unless symptoms arise. Malignant transformation should be suspected if the tumor grows after skeletal maturation. Complete resection with adequate negative margins is essential. Close follow up and genetic evaluation is recommended.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.