-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sorin N Mocanu, Mireia Botey Fernández, Francesc B Simó Alari, Ángel García San Pedro, Acute anterograde intussusception as a late complication of distal gastric bypass, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 9, September 2018, rjy248, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy248

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Small bowel intussusception is an uncommon cause of adult intestinal obstruction after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. It usually affects the Roux or the common limb at the jejunojejunostomy site and is mainly retrograde. An altered motility of the Roux limb seems to be the main explanation for its developement. We report the case of a patient with a late acute anterograde intussusception after a previous distal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Clinical, radiological and operative findings are presented and surgical solutions described in the literature are reviewed.

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal obstruction after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most feared complications in bariatric surgery. It affects 3,5–4% of the cases and the most frequent causes are internal hernias, peritoneal adhesions, jejunojejunostomy stenosis and incisional hernias [1, 2]. Small bowel intussusception (SBI) is a rare cause of obstruction, usually related with peristaltic anomalies that affect the Roux limb. We report a case of SBI in a patient with a previous distal RYGB.

CASE

A 42-year-old female patient was admitted to the emergency room for acute diffuse abdominal pain and nausea initiated 6 h before presentation. She had been operated eighteen years before for morbid obesity of an open distal RYGB with a common channel of 150 cm. The initial weight and BMI were 110 kg and 46 kg/m2. She had lost 55 kg corresponding to a 108% of excess weight loss. Three years after the RYGB she underwent an open mesh repair for an incisional hernia.

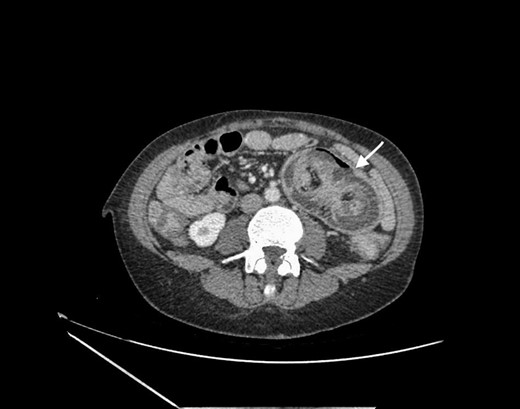

The clinical examination revealed normal vital signs and a moderate abdominal distention with tenderness at palpation in the left flank. Blood tests showed only a mild chronic anemia. The abdominal CT scan showed dilated small bowel loops located in the left abdomen and a ‘target’ sign suggestive of intussusception (Fig. 1).

Abdominal CT scan showing small bowel intussusception with the target sign (white arrow).

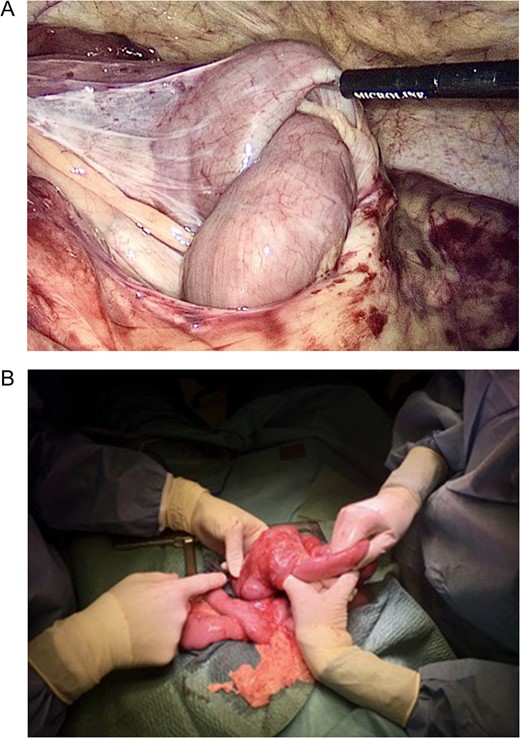

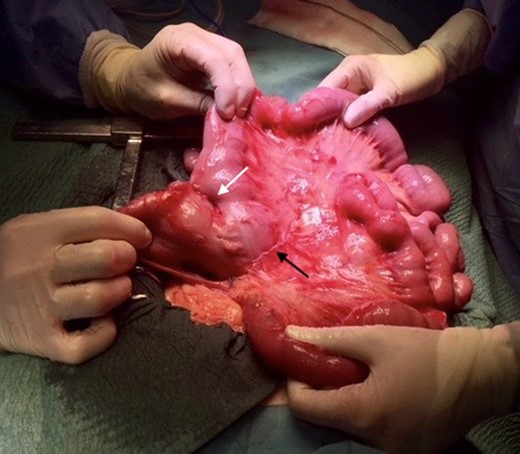

The patient underwent an exploratory laparoscopy with complete bowel inspection. At the site of the jejunoileostomy, an anterograde intussusception of the Roux limb with simultaneous twist of the anastomosis through the mesenteric defect were found, without ischemia (Fig. 2A and B). Laparoscopic reduction of the intussusception was attempted but the significant bowel wall edema precluded it. After conversion to midline laparotomy, manual desinvagination and reduction of the jejunoileostomy twist were performed. As no signs of irreversible ischemia were present, a conservative approach was agreed by the surgical team and a pexy of the distal Roux limb to the bilipancreatic limb was performed, using 2-0 Ty-cron stitches. The mesenteric defect was closed with a running 2-0 Ty-cron suture (Fig. 3) The postoperative recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged after one week remaining asymptomatic 3 months after the operation.

(A and B) Laparoscopic and open images of the intussuscepted bowel.

Surgical treatment. Pexy of the Roux limb to the biliopancreatic limb (white arrow) and closure of the mesenteric defect (black arrow).

DISCUSSION

SBI has been described seldom and its real incidence is not known since most of the published articles are case reports. However, in three published series that gather the majority of cases described in the literature the incidence was 0,1–1,3% [3–5]. The mean interval between RYGB and SBI is 3.6 years [6] and more than 90% of the patients are women [3, 4]. Both antegrade and retrograde types of SBI have been described after RYGB but most of the published cases were retrograde and occurred at the site of the jejunojejunostomy [3, 4, 6]. Contrary to most cases of adult SBI, which are anterograde and in which a mechanical cause is found and acts as a ‘lead point’, no clear explanation exists regarding RYGB-related intussusception. A motility disorder proposed by Hocking et al. [7] is the most accepted hypothesis.

The main peristaltic anomalies described in the Roux limb are the absence of the ‘fed pattern’ and the aberrant propagation of the migrating motor complexes originated in ectopic jejunal pacemakers [8]. Hocking’s theory suggests that the collision at the jejunojejunostomy of the peristaltic waves initiated in the biliopancreatic limb with those from the Roux limb generate a high pressure that could act as a ‘lead point’ favoring the intussusception. No cases of SBI have been described after biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch up to date, which suggests that maybe the distal small bowel lacks pacemaker properties similar to those of the proximal jejunum [6].

The significant weight loss induced by the RYGB seems to favor the development of SBI. In a review of patients with SBI after RYGB, the mean excess weight loss at the time of diagnosis was 99,8%, significantly superior to the usual weight loss induced by the RYGB [6]. The loss of visceral fat and the thinning of the mesentery opposes less resistance to the abnormal peristalsis favoring the intussusception.

Clinical presentation is dominated by abdominal pain, accompanied by signs of intestinal obstruction in 73% of the cases and occasionally by digestive bleeding due to mucosal injury [6, 9]. The diagnosis is usually confirmed with an abdominal CT scan which in many cases will identify the typical ‘target sign’ suggestive of intussusception.

Different surgical approaches to SBI after RYGB have been described: simple reduction, anastomotic revision with jejunojejunostomy resection and reanastomosis and imbrication/plication of the anastomosis [3–5]. Pexy of the biliopancreatic limb to the common channel was described in one case [10]. The optimal treatment is unknown because recurrences and reinterventions were described after each of the aforementioned procedures. Simper et al. [3] suggested a more definitive solution by restoring or preserving the continuity of the bowel through a bypass reversal or by performing an uncut Roux-en-Y with distal biliary diversion.

The distinctive feature of our case is the presence of an anterograde SBI of the Roux limb in a patient with a distal gastric bypass, with simultaneous twist of the jejunoileal anastomosis that, in our opinion, favored the intussusception. We think that the anastomotic twist was possible due to the lack of closure of the mesenteric space adjacent to the biliopancreatic limb. Female gender and the prior significant weight loss were in line with the literature mentioned earlier. The significant time lapse (18 years) between the RYGB and the complication, the distally located anastomosis and the anterograde SBI are contrary to the usual retrograde SBI described above. Thus, we consider that the dysmotility theory is less applicable in our case. Instead, the presence of the mesenteric defect seems a more plausible hypothesis and highlights the crucial importance of this technical aspect in the pathogenesis of intestinal obstruction after RYGB. The surgical solution to our case was dictated by the absence of ischemic signs and on the other hand by the perceived etiology of the complication. The intestinal pexy was intuitively used and seems to have worked, at least in the short term. We considered inevitable the closure of the mesenteric defect, preventing thus future complications.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.