-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mutlaq Almalki, Waed Yaseen, Cecal ameboma mimicking obstructing colonic carcinoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 6, June 2018, rjy124, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy124

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ameboma is a mass of granulation tissue with peripheral fibrosis and a core of inflammation related to amebic chronic infection. The initial presentations of colonic ameboma usually include obstruction and low gastrointestinal bleeding. It may mimic colon carcinoma or other granulomatous inflammatory conditions of the colon in both the clinical presentation and the endoscopic appearance. Here, we report a case of a 45-year-old male with a presentation of abdominal pain and constipation, as well as clinical, radiological and endoscopic presentation resembling colonic carcinoma, that was managed operatively with right hemicolectomy and post-operative histopathologic finding of cecal ameboma.

INTRODUCTION

An ameboma (amebic granuloma) consists of a firm, nodular, granulomatous inflammatory mass with multiple small abscesses, which is a rare complication of invasive infection with the protozoal organism Entamoeba histolytica. It has an induced onset and nonspecific symptoms that may include a right lower quadrant mass in the cecum, symptoms of partial or complete intestinal obstruction and low gastrointestinal bleeding [1]. Here, we report a case of colonic amebiasis, in which the symptoms and radiological findings closely resembled an obstructing right‐sided colonic carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old Saudi male, heavy smoker and drug addict, was presented to our hospital emergency department with complaints of generalized abdominal pain for 7 days prior to presentation. The pain was all over the abdomen, severe colicky in nature, associated with frequent nausea and vomiting of gastric contents, constipation for 4 days for which patient was taking over the counter herbal laxatives. It was also associated with weight loss and anorexia. The patient had no history of recent travel but had experienced similar symptoms before that improved without any medications. Also, he had surgery for perforated peptic ulcer 6 years prior to presentation.

On examination, patient was pale and cachechic. The patient’s blood pressure was 105/73 mmHg, heart rate was 89 beats/min and body temperature was 37.5°C. His abdomen was distended with midline laparotomy scar and visible peristalsis, soft on palpation with mild tenderness over the lower abdomen, positive bowel sounds, the local rectal examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations of blood chemistry analysis were within normal (10.4 mg/dl hemoglobin, 9 270 WBC/μl) coagulant function (49.9 s aPTT), HIV was negative. Further, albumin (3.13 g/dl) and mildly elevated LDH (358 IU/l) were revealed. Abdominal X-ray revealed distended small bowel loops with multiple air-fluid levels.

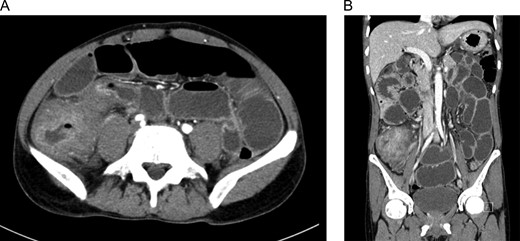

Patient was admitted for investigation. Abdomen and pelvis enhanced CT were performed revealing a swollen and edematous colon, small bowel dilatation mainly at ilial loops down to the level of the terminal ileum and cecum as there was inflammatory wall thinning and narrowing of the lumen, with normal remaining parts of colon (Fig. 1). Also, there were enlarged lymph nodes adjacent to the cecum and ileocecal junction with mild free fluid. For serology, the TB tuberculin test, HIV serology, stool analysis and upper endoscopy showed lower esophagitis, narrow inflamed pylorus and bulb of duodenum deformed with inflamed edematous mucosa with sessile polyp (biopsies were taken). Lower endoscopy showed inflamed edematous mucosa obstructing the lumen of the cecum (multiple biopsies were taken from cecum as well). Histopathology for upper endoscopy was unremarkable but biopsies from the colonic mass showed chronic unspecific inflammation with focal surface ulceration with lymphocytic infiltrate, mild edema in lamina propria and evidence of specific infection, granulomatous formation, and crypt abscess.

(A) and (B) Abdomen CT with IV and oral contrast showed small bowel obstruction secondary to cecal mass.

Surgical treatment was indicated with the provisional diagnosis of an obstructing cecal mass, suspected to be a right-sided colonic carcinoma. The patient was offered surgery but he refused and opted to be discharged against medical advice.

Two weeks later, the patient came back to our ED with a complaint of severe colicky lower abdominal pain for 4 days, which was worsening with time, associated with nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Patient gave consent for surgery.

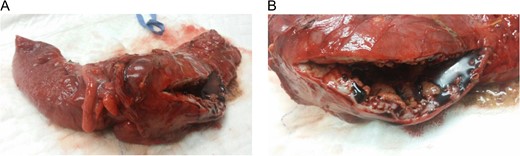

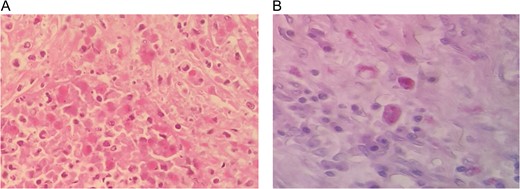

Laparotomy revealed a mass in the cecum and dilated terminal ileum loops; right-sided colon resection was performed and the resected colon was sent for histopathology and microscopy (Fig. 2). Histopathology slides of right colon showed surface ulceration with chronic inflammatory cells infiltrated in the colon wall and ameba trophozoites are seen in a group in the submucosa. All features are consistent with ameboma (Fig. 3).

(A) and (B) Resected bowel of a 45-year-old male with an obstructing right-sided colonic mass.

Post-operative course was uneventful, except for abdominal wound infection which was treated conservatively with daily dressing. The patient was discharged after full recovery. After discharge, we lost contact with the patient as he didn’t attend his OPD appointment.

DISCUSSION

Ameboma is a rare complication of amebic colitis, occurring approximately in 1.5–8.4% of cases [1]. Patients with long-standing or partially treated infection develop tumorous, exophytic, cicatricial and inflammatory masses known as ‘amebomas’ or amebic granulomas. The tissue necrosis in amebic colitis is replaced by an extensive inflammatory reaction and pseudotumor formation, possibly because of secondary bacterial infection that mimics colon carcinoma [2, 3]. Amebomas are usually solitary, variable in size and can be up to 15 cm in diameter. Men within the second and fifth decade of life are most commonly affected [2, 4].

It has an induced onset and nonspecific symptoms that may include right lower quadrant mass in the cecum, symptoms of partial or complete intestinal obstruction due to intestinal lumen narrowing and low gastrointestinal bleeding diarrhea. It may also cause fever and weight loss. The major complications of ameboma include perforation, obstruction, intussusception, anorectal fistula and appendicitis [5]. This occurs more frequently in patients untreated or inadequately treated during the course of an amebic colitis many years after dysentery. Immigrants from or travelers to endemic regions, malnourished patients, infants and the elderly, patients receiving glucocorticoids and patients with malignancy may have an increased risk for development and progression of the disease [1].

The most reliable method of differential diagnosis is biopsy in 60% of the cases. This must be taken directly from the ulcerated base of the lesion and must demonstrate the causative agent, the ameba, in trophozoite form [5]. However, these masses can still be visually indistinguishable from colonic carcinoma, and a diagnosis cannot be obtained via endoscopic study in nearly one-third of patients [4], with negative biopsies due to inadequate specimens or lack of appreciation of amebiasis on the part of the pathologist, or both [5]. Differential diagnosis must be made with Crohn’s disease, appendix abscesses in younger patients and colon cancer or diverticulitis in the elderly [4].

Ameboma is uncommon and is often diagnosed after surgical interventions due to insidious onset and variability of signs and symptoms [6].

In our case, the findings on imaging, mentioned earlier, were strongly suggestive of a colonic malignancy. In addition to that, the endoscopic biopsy histopathology of the mass showed chronic unspecific inflammation with no evidence of amebic trophozoites. Surgical resection was performed because of obstructing colonic cecal mass and the possibility of colonic malignancy. At laparotomy, an inflammatory mass involving the right colon was confirmed, and so the patient underwent a right hemicolectomy.

Few similar case reports, where colonic amebiasis, mimicked an obstructing right‐sided colonic carcinoma have been reported in literature [7–11]. In México, Rodea and Cols analyzed 25 840 urgent abdominal surgeries from 1970 to 2007, with 129 cases with colonic complications secondary to amebiasis. From the previous, only six ameboma cases were reported, all of them in the right colon, presented with acute abdomen or intestinal obstruction signs, only diagnosed after surgery by histopathological exam [12].

This case highlights the diagnostic uncertainty that may occur in patients with amebic colitis due to its ability to mimic colonic carcinoma, particularly if there is no definite recent history of travel to an endemic area. Colonic resection is indicated when neoplasia cannot be excluded or emergency care of complications such as perforation, abscess, obstruction, and intussusception [13].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Both authors contributed significantly and in agreement with the content of the manuscript. The senior author performed the surgery. Both authors participated in the literature review, data collection and writing of the final draft.