-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mehmet Tolga Kafadar, İbrahim Teker, Mehmet Ali Gök, Esat Taylan Uğurlu, İsmail Çetinkaya, Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to abscess in a hemodialysis patient: a rare and fatal cause of acute abdomen diagnosed late, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 5, May 2018, rjy103, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Splenic abscess is a very rare condition in the general population. It is more likely to develop in association with underlying comorbidities and trauma. More attention should be paid in patients with immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and congenital or acquired immunocompromise. Splenic rupture secondary to nontraumatic abscess causing acute abdomen is a rarer condition. Herein, we report a 55-year-old hemodialysis patient who presented with signs and symptoms of late generalized peritonitis. The patient was operated under emergency conditions and diagnosed with splenic abscess rupture, for which splenectomy with drainage procedure was performed. In such patients, the morbidity and mortality rates vary depending on the intraoperative and postoperative risks.

INTRODUCTION

Splenic abscess is a rare condition in clinical practice with a frequency ranging from 0.2 to 0.7% in autopsy series. If the condition is left untreated, its mortality reaches 100% [1]. There are difficulties in emergency surgery due to the prognostic nature of the splenic abscesses. As a result of the insidious course of clinical symptoms, it is difficult to diagnose and a missed diagnosis is a very likely occurrence. For a definitive diagnosis to be made, the disease must be first suspected. Early diagnosis and timely initiation of treatment will prevent its destructive late complications [2]. In this article, we present an immunosuppressed patient with splenic abscess rupture as a rare cause of acute abdomen who was diagnosed late and thus had a mortal course.

CASE REPORT

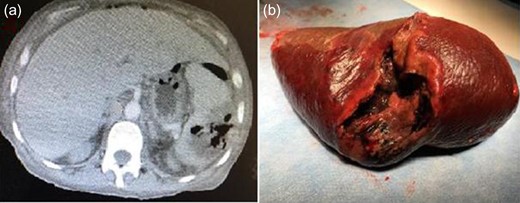

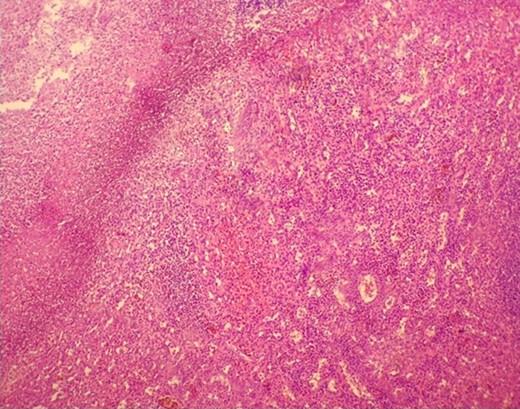

A 55-year-old female patient was examined in the emergency department with abdominal pain that had been persistent for ~10 days and having been aggravated for the last 3–4 days. Her past history was notable for diabetes mellitus (DM) for ~25 years. Additionally, she had undergone a coronary by-pass operation 10 years ago and a left infrapatellar amputation 4 years ago. Chronic renal failure had been diagnosed 2 years ago and she had been receiving hemodialysis treatment three times a week for the last 1 year. She had no history of abdominal trauma. Laboratory tests resulted with; White Blood Cell: 15 100/mm3, Hemoglobin: 8.5 g/dL, C-reactive protein: 40 mg/dL, Urea: 37.9 mg/dL, Creatinine: 2.25 mg/dL, Albumin: 2.4 g/dL, Sodium: 134 mmol/L, Potassium: 3.1 mmol/L, Calcium: 7.9 mg/dL, Glucose: 329 mg/dL and other biochemical parameters were normal. The abdomen was diffusely tender, and she also had guarding and rebound tenderness during the physical examination. Blood temperature was 38.7°C. An abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed diffuse intraabdominal free fluid collection. On an abdominal computed tomography (CT) there were free fluid collections in all abdominal quadrants; there also existed intraabdominal minimal free air images. There were air-fluid images in the splenic parenchyma (abscess?, perforation?) (Fig. 1a). The radiology department reported that it may be a gastrointestinal perforation. Based on the current findings, the patient was urgently operated according for a preliminary diagnosis of acute abdomen. Intraabdominal seropurulent fluid of ~2000 ml was aspirated perioperatively. There were diffuse fibrin matrixes in the entire peritoneum. No intestinal perforation was noted during exploration. There was a perforated abscess pouch with a size of ~8 × 6 cm2, which expanded posteriorly from splenic hilus and partly contained necrotic foci (Fig. 1b). Splenectomy and drainage were performed and the abdominal cavity was irrigated with abundant isotonic saline. Patient was postoperatively monitored in intubated state at intensive care unit. No proliferation occurred in her blood culture. Escherichia coli was isolated from the abscess culture, however, and Meropenem 500 mg I.V. (three times a day) and Metronidazole 500 mg I.V. (three times a day) treatment was commenced as recommended by the infectious diseases department. Her dialysis program was maintained according to blood parameters. The patient died on postoperative Day 25 due to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Histopathologic examination revealed suppurative inflammation and abscess formation of the splenic tissue (Fig. 2). Informed consent was obtained from her son who participated in this case.

Abdominal computed tomography scan showing splenic abscess (a), the macroscopic view of the splenectomy specimen (b).

Microscopic view of suppurative inflammation, and abscess formation in the spleen. In the upper left corner fibrin, and most of the abscess formation that necrotized neutrophil leukocytes cause to nuclear debris is seen.

DISCUSSION

Because the spleen is a reticuloendothelial tissue and serves as an effective filter for microorganisms, the incidence of splenic abscess is lowest among all body abscess types [3]. Splenic abscess has been reported to develop as a consequence of septic microembolism of the spleen. Although splenic abscess has a wide variety of causes, it is most often associated with trauma and infection. Infection usually occurs in the form of a secondary infection in an ischemic infarct region or distant metastasis of infective endocarditis. Aerobic microorganisms are the most common infectious agents, particularly staphylococci, streptococci, Escherichia coli and salmonella. In addition, it emerged as a major risk factor for immunosuppression, hemoglobinopathy and DM [4].

Clinical diagnosis of splenic abscess is difficult due to its rare appearance and various clinical signs. It is a condition that needs to be suspected on the basis of vital signs during physical examination, especially when there exist some underlying risk factors. It is an extremely fatal condition when left untreated. The most common symptoms are pain localized in the upper left abdominal quadrant, fever, nausea and pleural effusion. Leukocytosis is present in most patients (78%). When an abscess is ruptured, acute abdomen and generalized peritonitis ensues, when intraabdominal free air may develop [5]. Culhaci et al. [6] reported that they operated all patients with splenic abscess due to clinical signs and symptoms of acute abdomen, and discovered splenic abscess rupture in two of them.

Recent developments in radiological techniques have influenced diagnosis and approach. US is the first diagnostic tool to distinguish noninvasive and solid lesions from cystic lesions; however, US cannot clearly distinguish infarct and abscesses from each other. US did not help us with the diagnosis of our patient. Contrast-enhanced CT is more successful in this regard, allowing a diagnosis with 96% sensitivity [7].

Traditionally, the treatment of splenic abscess is the use of I.V. antibiotics as well as splenectomy. One of the newer methods is percutaneous drainage. Especially in younger patients, splenectomy is avoided due to the fear of future immunological dysfunction. If the abscess is unilocular or bilocular, surrounded by a separate wall, if there are no internal septations, and if the fluid content is appropriately fine for drainage, percutaneous drainage is considered as the primary treatment [8]. However, it has also been reported that a long-term antibiotic therapy as well as US or CT follow-up can be adequate when there is infection as evidenced by a microorganism-positive blood culture and/or the lesion is small and solitary [9]. Patients treated with ampicillin–sulbactam, chloramphenicol and ciprofloxacin have been reported in the literature. However, surgical treatment is inevitable for splenic abscess rupture causing acute abdomen [10]. In our case, drainage plus splenectomy was performed due to a clinical state of delayed general peritonitis.

CONCLUSION

Splenic abscess is a very rare clinical entity that has a high mortality rate when left untreated. Especially among patients who are septic, immunosuppressed, febrile, intraabdominal infection and splenic abscess rupture should be remembered in the differential diagnosis. After a rapid evaluation of a patient with findings of acute abdomen using a procedure to reach the diagnosis, appropriate surgical treatment should be performed in a multidisciplinary fashion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

FUNDING

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from the son of the patient.