-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francisco Díaz-Cuervo, Lina Posada-Calderon, Natalia Ramirez-Rodríguez, C. Felipe Perdomo, Gabriel A. Duran-Rehbein, Pylephlebitis with splenic abscess following transrectal prostate biopsy: rare complications of intra-abdominal infection, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 7, July 2017, rjw075, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw075

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pylephlebitis is a rare complication of intra-abdominal infection involving septic thrombosis of the portal system. If the splenic vein is compromised, this can lead to a splenic abscess, an extremely rare complication of pylephlebitis. The pathophysiology behind these clinical entities remains unclear. In both cases, symptoms are highly nonspecific and include fever, malaise and abdominal pain. Here, we discuss a case in which a patient develops both pylephlebitis and a subsequent splenic abscess following a transrectal prostate biopsy. Diagnosis was made by computerized tomography scan; the treatment included broad spectrum antibiotics and laparoscopic splenectomy, after which the patient made a full recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Pylephlebitis is a rare condition characterized by the suppurative thrombosis of the portal vein [1]. It results as a complication of any intra-abdominal infection that has venous drainage to the portal system. Symptoms are nonspecific, and patients usually present with fever and abdominal pain in the setting of an existing infection or a previous abdominal intervention [1].

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old man presented to the emergency department after discharge against the medical advice from another institution. He initially presented with symptoms of abdominal pain, malaise, fever and dysuria for 20 days. These symptoms had been managed with oral antibiotics with no improvement. The symptoms began after a transrectal prostate biopsy, which had subsequently been positive for prostate cancer. The patient’s medical history was significant for benign prostatic hypertrophy. Regular medication included only tamsulosin. In the other institution the patient initially received intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics. After several days of this management, he developed respiratory distress and a computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed, which demonstrated a subcapsular splenic abscess and pleural effusion complicated by empyema. That institution lacked a Thoracic Surgery department, so the patient came to our institution.

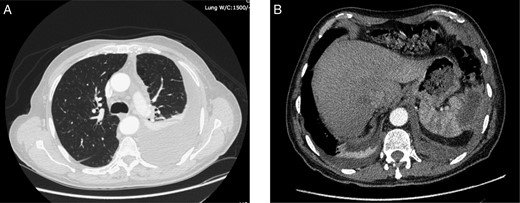

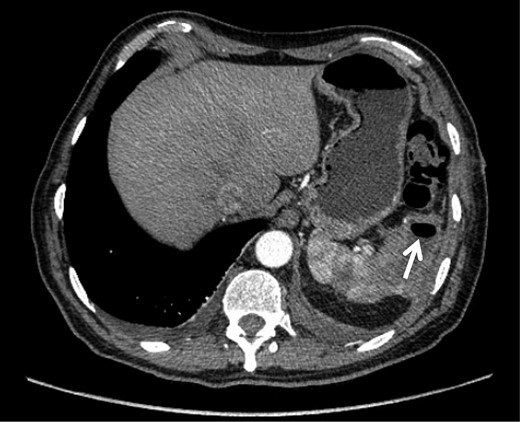

On admission, physical examination revealed normal vital signs and decreased breath sounds over the right pulmonary base as well as diffuse abdominal tenderness that was worse over the left hypochondrium. Blood culture samples as well as a complete blood count that revealed a normal hemoglobin and white cell count were taken. A CT scan confirmed the previously mentioned findings (Fig. 1). The patient was started on the same i.v. antibiotics he had been receiving (meropenem) and then taken to the operating room (OR) for video-assisted thoracoscopic lung decortication/pleurectomy. General surgery was then asked to assess the splenic abscess and, in consultation with interventional radiology, chose to treat conservatively. Two days later, the antibiotic regimen was simplified to i.v. ertapenem. After 4 days of this management, a new CT showed that the abscess had grown in size and had gas within it (Fig. 2). The decision was made to take the patient to the OR for a laparoscopic splenectomy.

CT scan taken on admission showing. (A) left-sided pleural effusion with empyema and septal loculations and (B) a subcapsular splenic abscess of approximately 5 cm × 2 cm × 3 cm with an approximate volume of 14 cc.

CT scan taken 5 days after admission demonstrating an increase in the size of the splenic abscess as well as the presence of gas within its walls (arrow).

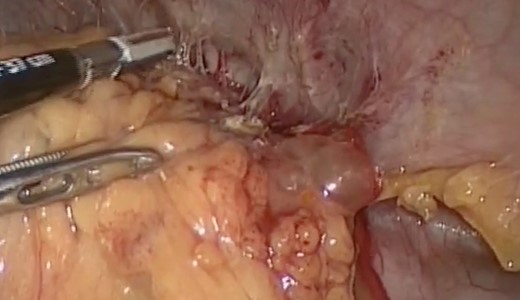

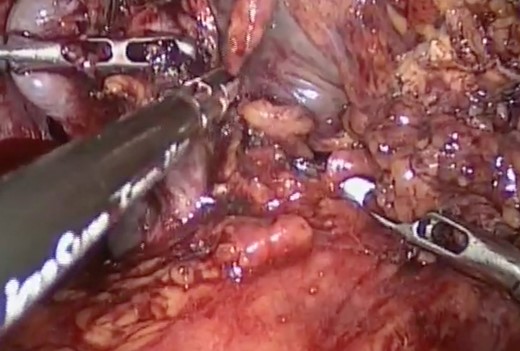

Intraoperative findings included extensive inflammation involving the inferior half of the spleen, the splenic flexure of the colon and the distal pancreas, as well as the abscess in question which contained approximately 10 cc of purulent material (Figs 3 and 4). The final surgical specimen included the entire spleen and the histologic report of pancreatic tissue compromised by the abscess. The patient was transferred to the surgical ICU for 24 hours. The following day, the blood cultures taken on admission grew an extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli resistant to carbanemic agents and sensitive to tigecycline. The antibiotic regimen was modified accordingly, and after 7 days the patient was discharged symptom-free and with a plan to complete 15 days of tigecycline at home.

Splenic mass, inflammatory adherences from the major momentum to the spleen, colon and diaphragm.

Inflammatory tissue dissection and drainage of the splenic abscess.

DISCUSSION

Pylephlebitis may occur secondary to intra-abdominal infection, but in 32% of cases the cause is unknown or unidentified [2]. Most cases of pylephlebitis have been attributed to diverticulitis or appendicitis [1, 3]. However, current evidence has shown pancreatitis as an important etiology [4]. Recent intra-abdominal procedures, inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppression are other clinical conditions that have been associated with the development of pylephlebitis [1].

Diagnosis is made by confirming the presence of thrombi in the portal vein or its tributaries in the context of abdominal infection. Visualization of the thrombi can be achieved with an ultrasound or a contrast-enhanced CT scan [3]. Blood cultures may be positive only in 44% of cases although bacteremia develops in 23–88% of patients [4]. In such cases, the most commonly isolated microorganisms are Streptoccocus viridans (24%), E. coli (21%) and Bacteroides fragilis (12%) [4].

The most common complications of pylephlebitis are extension of thrombi into the superior mesenteric vein, splenic vein and intrahepatic branches of the portal vein, hepatic abscess formation and bowel ischemia [1, 4]. Hepatic and splenic infarctions as well as peritonitis and other intra-abdominal abscesses leading to death have also been reported [4]. Splenic abscess, although not described in the literature as a direct complication of pylephlebitis, may occur as the septic thrombi in the splenic vein, which reach the spleen.

Splenic abscesses represent up to 5% of all intra-abdominal infections and have a mortality of 47–100% [5]. Although the pathophysiology behind their formation is somewhat unclear, one of the proposed mechanisms is hematogenous septic embolization from an infectious focus to a previously healthy spleen [6]. Like pylephlebitis, symptoms are usually nonspecific involving fever (90%), pain in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen (60%), abdominal tenderness and splenomegaly [5]. CT scan is considered the gold standard for diagnosis [5].

Goals of treatment in pylephlebitis include administration of systemic antibiotics and elimination of the primary septic focus [3]. Antibiotic therapy should cover Gram-negative enterobacteria, Streptococcus spp. as well as anaerobes and should be administered for 4–6 weeks [2].

The treatment of splenic abscesses that arise as a result of pylephlebitis includes percutaneous drainage or surgical removal. The abscess should be drained either percutaneously if it is small and easily accessible or in open drainage [5]. If there are multiple abscesses of irregular or complicated access, splenectomy is preferred [7].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.