-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Juan C. Mejia, Mei Dong, Okechukwu Ojogho, Pancreaticoduodenectomy in a patient with previous left ventricular assist device: a case report with specific emphasis on peri-operative logistics, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 3, March 2017, rjx053, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx053

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To the best of our knowledge this is the first case of this nature described in the literature. Sharing the authors experience with this case, particularly the technical challenges and post-operative management may aid other physicians facing similar scenarios. In this report, we describe a pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a patient with a previous left ventricular assist device (LVAD). A multidisciplinary approach, particularly close involvement of the advanced heart failure, mechanical heart and pancreas surgery teams was key to the success of this case. Major abdominal surgery in the setting of previous LVAD should be considered carefully, however, the LVAD should not be generalized as an absolute contraindication.

INTRODUCTION

Over 2500 continuous left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) devices were implanted in United States in 2014 and over 20 000 have been implanted worldwide to date [1]. With the increasing prevalence of ventricular assist devices, non-cardiac surgeries for this patient population are becoming a more frequently encountered clinical scenario. Patients with adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas who undergo surgery and adjuvant therapy have a 5-year survival of approximately 20% [2]. Patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas who are not surgical candidates and receive only chemotherapy with or without radiation have a median survival of ~7–10 months [3]. Clearly, surgery plays a critical role in the potential survival of patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Herein, we present a patient with an LVAD who was subsequently diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. After careful consideration of the overall prognosis in this patient with this complex clinical presentation, we elected to perform a pancreaticoduodenectomy.

CASE REPORT

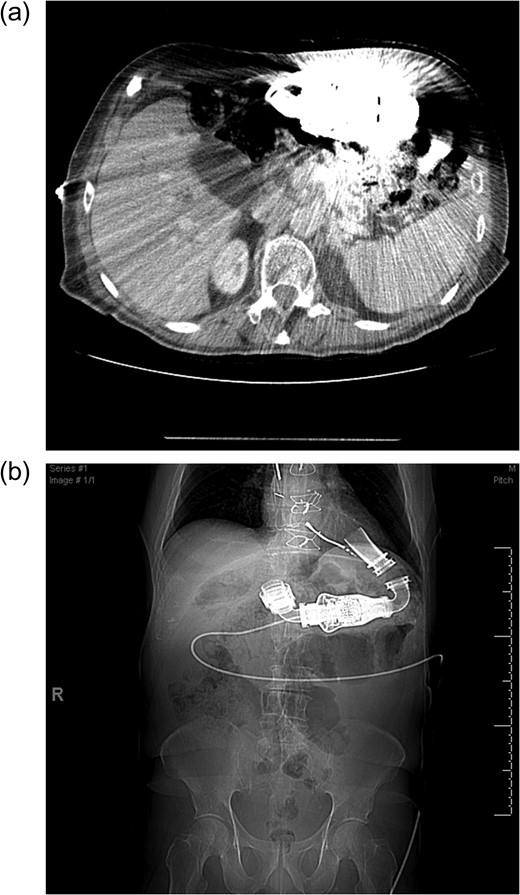

(a) Cross sectional imaging as a pre-operative study to define the pancreatic anatomy is limited by the LVAD artifact. (b) Computed tomography scout film shows the location of the LVAD and LVAD driveline in the chest and abdomen.

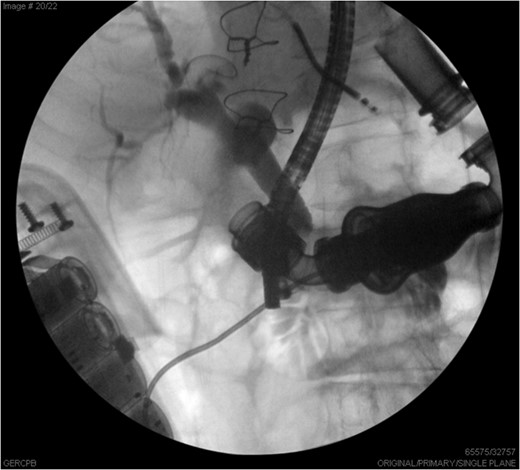

ERCP images illustrate the common bile duct with distal stricture, partially obstructed by the LVAD.

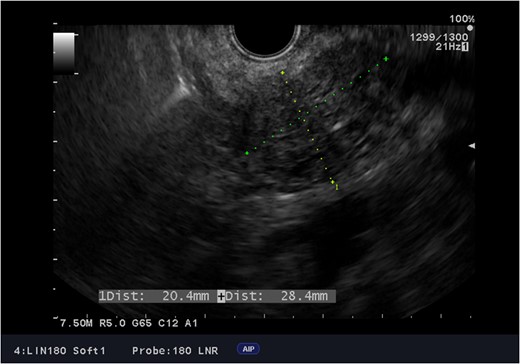

Endoscopic ultrasound images of the adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas.

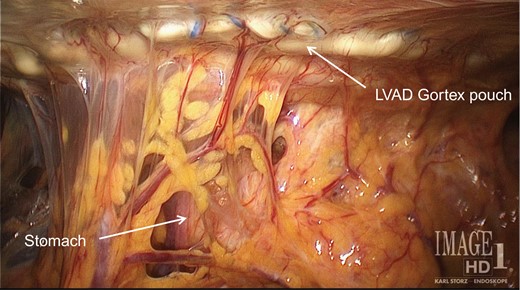

A pouch made of Gortex and secured to the inferior face of the diaphragm houses the LVAD and sits over the mid and upper quadrants of the abdomen.

Approximately 6 weeks after surgery, he was started on adjuvant chemotherapy with single agent Gemcitabine. He completed total of 6 months of Gemcitabine without major side effects.

At the time this report was drafted, the patient was 30 months out from surgery with no evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer pre-operative imaging

Due to LVAD streaking artifact on CT, pre-operative good quality imaging of the pancreas was only possible with endoscopic ultrasound.

Surgical challenges

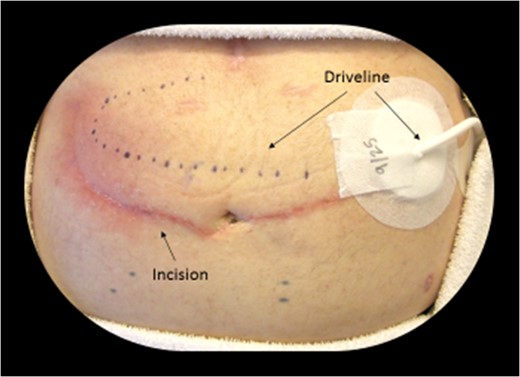

Incision (presence of the LVAD driveline—Fig. 3)

Dotted line shows the subcutaneous location of the driveline (LVAD power cord). A typical midline incision or subcostal incision was not feasible due to the driveline trajectory.

Retraction and exposure

Components of the inflow and outflow cannulas of the LVAD are made of pliable materials, therefore continuous intra-operative flow monitoring by a mechanical heart engineer is required for these cases.

Linear flow (HeartMate CF) and identification of vascular structures

Identification of the superior mesenteric artery, celiac artery, hepatic artery, gastroduodenal artery or any arterial anatomic variants (i.e. replace right hepatic artery) is key to the operation. In patients with previous LVAD the lack of arterial pulsatile flow makes identification of these structures by palpation or Doppler not possible. Intra-operative ultrasound plays a bigger role for identification of vascular structures.

Post-operative anticoagulation

LVAD patients are routinely kept anticoagulated with a target INR (international normalized ratio) between 1.8 and 2.5. In our case, the INR was corrected and the patient was kept on a heparin drip until two hours prior to surgery. Full dose intra-venous heparin drip was started on post-operative Day 2 and Coumadin was started on post-operative Day 3.

CONCLUSION

Close collaboration with the LVAD team is key to the successful care of these patients. Based on our limited experience, currently at our institution previous history of LVAD is not an absolute contraindication for major abdominal oncologic surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There was no funding for the writing of this case report. The authors appreciate the support of all the healthcare providers involved in the care of the patient referenced.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.