-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

N. Merali, M. Yousuff, K. Lynes, M. Akhtar, A case report on a rare presentation of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 3, March 2017, rjw197, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw197

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We describe a highly unusual case of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) that presented as a large polyp protruding from the anal canal. A 67-year-old man presented with rectal bleeding and mucus discharge. At examination under anaesthesia, a large pedunculated polypoidal lesion was found, measuring 25 × 20 mm, arising posterolaterally from the anorectal junction and protruding externally 50 mm in size. SRUS can be a misnomer as the condition can present in a number of different ways and only a minority of patients has a solitary ulcer. Other findings include multiple ulcers, hyperaemic mucosa or a broad-based polypoidal mass. In this case, a rare presentation of SRUS in the form of a large polyp was confirmed by histology. A key learning point is to remember that although less common than other causes of rectal symptoms, it should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis once sinister causes have been excluded.

INTRODUCTION

Cruveilhier [1] described four cases of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS), a chronic and benign lesion of the rectum. It is an uncommon condition with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 100 000 people per year [2]. SRUS is characterized by typical clinical features and histopathological abnormalities. We describe a highly unusual case of SRUS that presented as a large polyp protruding from the anal canal.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old man presented with bright fresh rectal bleeding with copious mucus discharge. The patient complained of history of incomplete evacuation, excessive straining and constipation since childhood. His symptoms had worsened over the preceding 12 years and recently associated with perineal pain. He had previously undergone investigations for iron deficiency anaemia with an elective colonoscopy in 2012 revealing haemorrhoids only, a normal gastroscopy and normal MRI of small bowel. He had no significant comorbidities.

Abdominal examination was unremarkable, on rectal examination, a large polypoidal growth was found to be protruding from the rectum with surrounding circumferential haemorrhoids. Digital rectal examination was not possible due to pain and partial obstruction of the lumen by the polypoid lesion. In view of his symptoms, an urgent examination under anaesthesia (EUA) of rectum with excision biopsy of the polyp was arranged.

At EUA, a large pedunculated polypoidal lesion was found, measuring 25 × 20 mm, arising posterolaterally from the anorectal junction and protruding externally 50 mm in size. Circumferential third degree haemorrhoids were noted. Rigid sigmoidoscopy up to 15 cm revealed normal rectal mucosa. The large polyp was excised down to the muscle at the dentate line and sent for histology; the case was referred to the colorectal multidisciplinary meeting.

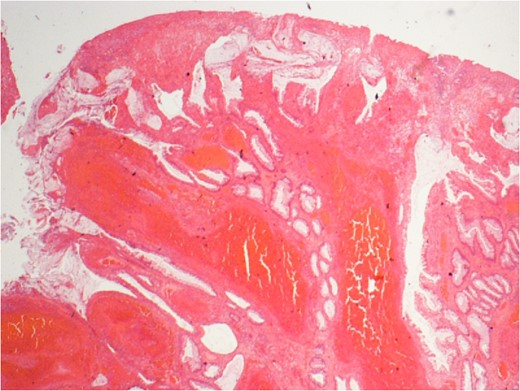

Extensive mucosal ulceration, mucosal prolapse and reactive glandular atypia.

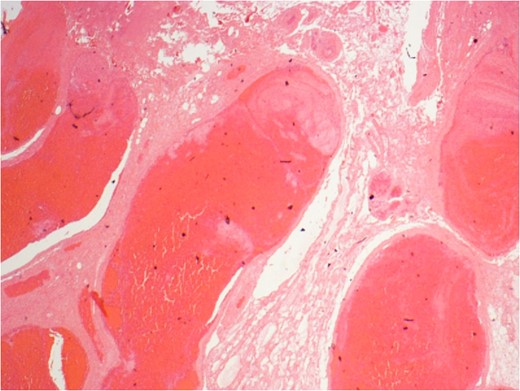

Vascular congestion and grossly dilated veins (haemorrhoids) with early intraluminal thrombus formation.

The post-operative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged with advice regarding lifestyle factors and conservative measures in order to improve rectal emptying and avoid further straining. A follow-up report at 8 weeks following discharge revealed that he was clinically well, the wound had healed and there was no evidence of recurrence.

DISCUSSION

SRUS is essentially a defecatory disorder; common symptoms include rectal bleeding, passage of mucous, perineal or rectal pain, tenesmus, incomplete evacuation, straining on defecation and rectal prolapse [3]. The syndrome affects men and women equally and although it typically affects young adults, it can occur at any age and up to 25% of patients will be aged over 60 at presentation [3]. SRUS is commonly misdiagnosed leading to an increased length of time from presentation of symptoms to accurate diagnosis [4]. In one series, 26% of people with SRUS were found to be asymptomatic and were only identified when being investigated for other pathologies [5]. Differential diagnoses that should be considered include inflammatory bowel disease, ischaemic colitis, pseudomembranous colitis and malignancy.

The term SRUS can be a misnomer as the condition can present in a number of different ways and only a minority of patients have a solitary ulcer [6]. Other findings include multiple ulcers, hyperaemic mucosa or a broad-based polypoidal mass. The underlying aetiology of the condition is poorly understood. Mucosal prolapse, overt or occult, is the most common underlying pathogenic mechanism in SRUS. Paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during defaecation is also a feature [3] and these opposing forces lead to an increase in rectal pressures [7]. Rectal hypersensitivity has also been suggested as a cause for the sensation of incomplete evacuation and repeated straining [8]. These factors lead to repeated trauma to the rectal mucosa and subsequent venous congestion, hypoperfusion and ischaemic injury, resulting in ulceration. Histopathological examination is key to the diagnosis of SRUS with classical characteristics of fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria, crypt distortion and disorientation of muscle fibres, as seen in this case [9].

In case series of SRUS reported in the literature, a polypoidal variant has been noted, and this variant may account for up to 32% of patients with SRUS [10]. The polypoid presentation in this case was atypical as these SRUS are usually located anteriorly, within the rectum, and are broad based. The appearances may be confused with an inflammatory polyp, hyperplastic polyps or rectal carcinoma resulting in a delay of diagnosis and treatment [10]. The polypoidal variant of SRUS has been noted to be the most common form in asymptomatic patients, leading some to propose that it may be a precursor lesion to ulceration. Polypoid lesions, of this type, have been termed ‘inflammatory cloacogenic polyp’ in some reports [10], this is a variant of SRUS and has very similar histopathological features. Even in reports of this subtype, a single large polyp such as this protruding from the anal canal has not previously been reported. As these lesions do classically arise from the anorectal junction, it is possible that the polyp in this case represented this form of SRUS. Polyps of this type have previously been shown to have the potential for malignant transformation and therefore excision is advised.

The choice of treatment for SRUS depends on the severity of symptoms and whether there is an underlying rectal prolapse. Conservative medical management consists of patient education, dietary modification, bulking agents, biofeedback therapy and topical therapies, including steroid, sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylate enemas. Surgical options for treatment of SRUS are reserved for patients who do not improve with conservative measures, and those with rectal prolapse. Procedures that have been carried out for SRUS include rectopexy, local excision, Delorme's procedure, perineal proctectomy (Altemeier's procedure) and diversion. In this case, a combination of excision biopsy with lifestyle and conservative measures aiming to prevent recurrence was used.

In this case, a rare presentation of SRUS in the form of a large polyp was confirmed by histology. A key learning point is to remember that although less common than other causes of rectal symptoms, it should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis once more sinister causes have been excluded. Maintaining a high index of suspicion from both the surgeon and the pathologist is required with a multidisciplinary approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to Dr Andreas Gavriil for providing the histological images shown.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interests and no financial ties to disclose.