-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Virgilio Galvis, Ruben D Berrospi, Juan D Arias, Alejandro Tello, Julio C Bernal, Heads up Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty performed using a 3D visualization system, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 11, November 2017, rjx231, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx231

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 68-year-old female underwent Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) in her right eye using a 3D visualization system with the surgeon looking directly to a digital screen instead of through the eyepieces of the surgical microscope. The procedure was uneventful. Five weeks after the surgery the DMEK graft was in good position and totally adhered, the cornea clear and uncorrected distance visual acuity 20/50. This is the first reported case of DMEK using 3D augmented reality visualization system. It seems to offer advantages for the corneal surgeon in critical steps of the endothelial grafting procedure.

INTRODUCTION

A currently available 3D visualization system consists of a High Dynamic Range (HDR) camera and a high-definition 3D screen, which allows the surgeon to operate directly looking at the monitor, instead of through the eyepiece of the surgical microscope. Some authors have called this approach head-up or heads up surgery [1–9]. This platform is currently mainly promoted for enhancing visualization during vitreoretinal surgery [4–7, 9]. However, it has also been used in anterior segment procedures, including Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) and non-DSAEK [4, 8]. Herein, we report a case of a Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) completed with the tridimensional visualization system. According to our knowledge this is the first DMEK performed using this device ever published.

CASE REPORT

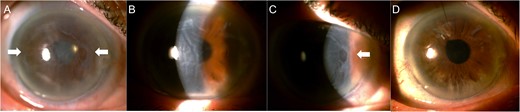

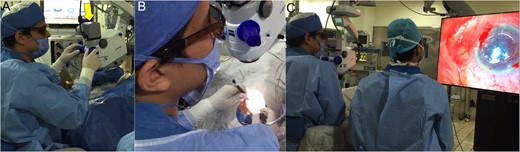

A 68-year-old female with pseudophakic bullous keratopathy underwent DMEK, which due to the shortage of donor tissue in our country only could be performed until 25 months after the phacoemulsification. Prior to the corneal transplant the cornea showed stromal and epithelial edema, and some changes of superficial stromal fibrosis sparing the visual axis (Fig. 1). Distance visual acuity was 20/800, which did not improve with optical correction. The procedure was performed by one of us (R.D.B.) using a 3D visualization system attached to the surgical microscope (Fig. 2). Both the surgeon and the assistant surgeon were wearing passive polarized 3D glasses and looking directly to the digital screen (Fig. 2).

Corneal edema in the right eye as seen before the corneal transplantation (A–C). Some subepithelial fibrotic changes were visible affecting from the periphery to the paracentral area (A and C, white arrows). The visual axis was free of fibrosis (B). Five weeks after excision of subepithelial fibrotic tissue and DMEK, the cornea regained its transparency (D).

The 3D visualization system's High Dynamic Range (HDR) was attached to the microscope in place of the eyepieces of the surgeon (A, yellow arrow). The surgeon adjusted the zoom and focus directly looking at the screen in front of him, and proceeded to perform surgical maneuvers in that ‘head-up’ position (B). Both the surgeon and the assistant surgeon wore 3D glasses with each lens polarized to make them see a different image through each eye, by filtering out incident light waves at certain angles (one the horizontal and the other the vertical ones), thus enhancing the stereoscopic effect (C).

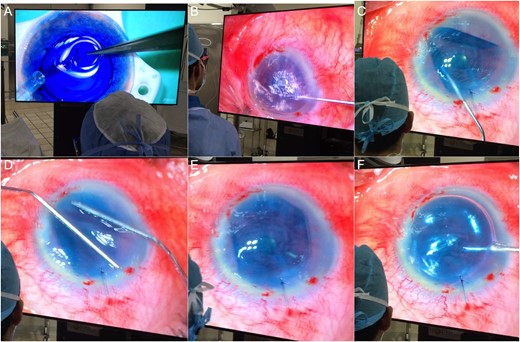

The donor tissue preparation was done by the surgeon using the 3D visualization system without problem (Fig. 3). Both the corneal epithelium and the layer of subepithelial fibrosis were initially removed with a surgical blade. The subsequent surgical steps were performed uneventfully using the digitally assisted tridimensional visualization system (Fig. 3).

(A) Donor tissue preparation: the double scroll is being aspirated into the injection device. (B) Descemetorhexis. (C) Unfolding of the Descemet graft inside the anterior chamber, with the hinge facing down as confirmed by the Moutsouris' sign. (D) Separation of the scrolls by gentle taps onto the outer cornea. (E) The DMEK roll is almost completely unfolded. (F) The step is completed injecting an air bubble. The images in the screen are not crystal clear since it is necessary to wear the 3D polarized glasses to see them perfectly defined.

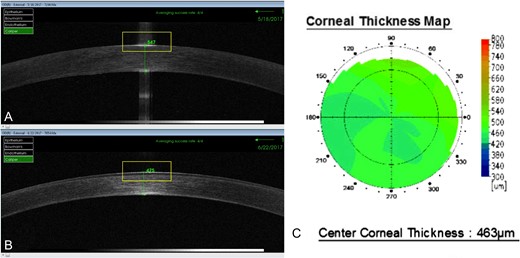

The first postoperative day the cornea was transparent, but completely deepithelialized and the patient referred severe discomfort. The DMEK graft was in good position and totally adhered as confirmed by anterior segment OCT (Fig. 4).

(A) Anterior segment OCT taken the first postoperative day showed that the DMEK endothelial graft was well attached and a central corneal thickness of 547 µ. (B and C) Five weeks later the corneal thickness diminished to between 463 and 475 µ.

Five weeks later, uncorrected distance visual acuity in the right eye was 20/50, with a refraction of Plano. The cornea had fairly good transparency and central corneal thickness was 463 µ, according to the anterior segment OCT (Figs 1 and 4).

DISCUSSION

During the microsurgical procedures it is critical that the surgeon has an image with excellent resolution, depth, clarity and contrast. Looking through the eyepiece of modern operating microscopes that are specifically designed to be used in an ophthalmic surgical setting, those goals are usually accomplished. However, although the field of view is wide, the surgeon is restricted to look to the surgical field only by moving his/her eyes due to the natural limit imposed by the eyepiece. A relatively new option is to use a special high-definition camera connected to the optics carrier of the microscope, which directs stereoscopic images and video to an ultra high-definition (4K), large, organic light-emitting diode 3D-enabled flat-panel display. Both, the surgeon and the assistant surgeon will not see through the microscope eyepieces to the surgical field, but directly to the digital flat-panel display. This was possible because the latency for the video feed is <100 ms. This so short delay was recently reached because of advances in digital technology, including chipsets and firmware for image capture, processing, and display of real-time high-quality digital video [9]. Digital imaging with full high-definition (full HD) resolution, i.e. 1920 pixels in width and 1080 pixels in height, produces image quality at least equivalent to 20/20 visual acuity. Using digital 3D high-definition with a horizontal resolution in the order of 4000 pixels (4K), also known as Ultra HD, which refers to a resolution of 3840 × 2160 pixels (around four times the 1 920 × 1080 pixels of a full HD television monitor) involves a much higher pixel density, and therefore it generates a clearer and better defined picture.

This yields very high stereoacuity (40 s of arc). Using this approach the surgeon may increase magnification while maintaining a very good depth of field. The depth of field with this 3D system is two to three times as deep as that of the standard surgical microscope if the visualization system camera aperture is reduced to 30% [9]. In addition, both the surgeon and the surgical team, by wearing passive polarized 3D glasses, can permanently view the complete surgical field (Fig. 2).

First clinical application of the system in cataract surgery was done by Weinstock, who reported good outcomes in a presentation in 2010 [1–3]. Eckardt and Paulo recently published a clinical study with more than 400 posterior vitrectomies. They also mentioned that at least one DSAEK was performed using the device, but did not include details of such cases [4].

Many other retinal surgeons have expressed their positive experiences using this 3D visualization system [4–7, 9].

The initial experience in our institution was similar, and a posterior segment surgeon (J.D.A.) felt very comfortable with the 3D visualization system after just a couple of cases. He highlighted that the improved stereopsis that the system offered was very helpful for epiretinal membranes and internal limiting membrane peeling, without the use of a contact lens. He agreed with other retinal surgeons that due to its better visualization it is very probable that the digitally assisted system will become a standard in the posterior segment surgical armamentarium [4–7, 9].

With regard to corneal transplant surgery, as indicated, Eckardt and Paulo mentioned performing DSAEK, and Mohamed et al. recently published a case of non-DSAEK [4, 8].

A newer technique for endothelial corneal grafting is DMEK, which has been shown to have very good short and middle-term outcomes [10]. One of us (R.D.B.) performed DMEK using this digitally augmented reality technology. The surgeon performed it the first day that he used the system, and only after carrying out a handful of cataract surgeries. He mentioned that it took him only two or three phacoemulsification cases to feel comfortable using the visualization system, and getting used to look at the television monitor instead than into the microscope eyepieces. The surgeon felt that the quality of the image was as least as good as seen through the surgical microscope but the contrast in the colors, the depth of field and the size/quality ratio in the large screen seemed to be enhanced. In the DMEK surgery, where it is critical to determine the correct position of the double scroll configuration of the donor tissue, the surgeon commented that the signs (including the Moutsouris´ sign) were much more evident in the 3D screen.

In conclusion, this digital platform of augmented reality appears to provide to the cornea surgeon a much more detailed vision, which is very useful in critical steps of the DMEK procedure, as determining the correct position of the scrolls of the donor tissue, and therefore seems to offer pluses for this type of surgery. Furthermore the great benefit of allowing the assistant surgeon and other people in the surgical room to have the same view than the surgeon is undoubtedly a disruptive advantage in a teaching institution.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.