-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kayla M Humenansky, Lauren Kopicky, Jude Leo Opoku-Agyeman, Carlos G Martinez, Splenic hematoma as a consequence of pneumoperitoneum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 10, October 2017, rjx209, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx209

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Splenic injury is a rare but serious complication of bariatric surgical procedures. Given that the need for dissection of the gastrosplenic ligament during bariatric surgical procedures, splenic injury is not unfathomable. While most subcapsular splenic hematomas may be self-limiting, continued expansion may result in splenic rupture and should, therefore, be handled with great care. With the growing rate of bariatric surgical procedures worldwide, inadvertent intra-operative splenic injury may become a more prevalent surgical complication. We report that the first documented case of subcapsular hematoma and associated gas collection following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, as well as, a proposed mechanism for the radiographic findings and potential complications.

INTRODUCTION

Splenic injury is a rare but serious complication of bariatric surgical procedures. Given that the need for dissection of the gastrosplenic ligament during bariatric surgical procedures, splenic injury is not unfathomable. Capsular tears are the most common type of injury [1–3]. The true incidence of inadvertent intra-operative splenic injury is unknown [2]. While most subcapsular splenic hematomas may be self-limiting, continued expansion may result in splenic rupture and should, therefore, be handled with great care. Total splenic inflow of blood is 5–10% of the total body blood volume per minute and rupture may result in serious and fatal hemodynamic consequences [4]. With the growing rate of bariatric surgical procedures worldwide, inadvertent intra-operative splenic injury may become a more prevalent surgical complication. Most documented cases of splenic injury following bariatric surgical procedures reference splenic infarction or simple hematoma as a complication [5]. We report that the first documented case of splenic injury with radiographic evidence of subcapsular hematoma and gas collection following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG), as well as, a proposed mechanism for the radiographic findings and potential complications.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old woman with morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea and a history of transit ischemic attack on Plavix underwent a laparoscopic SG with intra-operative esophagogastroduodenoscopy. She tolerated the initial procedure well; however, there was noted to be a small tear in the splenic capsule intra-operatively. Hemostasis was achieved using LigaSure™ electrocautery and Surgicel®, and the remained of the procedure was uneventful. She was noted to be mildly tachycardic post-operatively and throughout her initial hospital stay. Her hemoglobin remained stable and she was discharged post-operative Day 2, with instructions to resume Plavix on post-operative Day 5 after it had been held for 7 days pre-operatively.

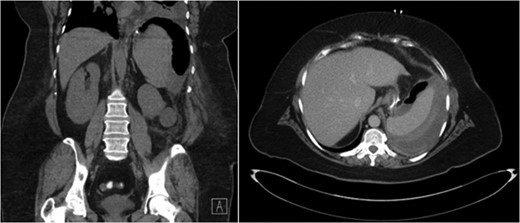

She represented 8 days after discharge with complaints of left upper quadrant abdominal pain. She denied dizziness, shortness of breath, chest pain or trauma to her abdomen. On physical exam her heart rate (HR) was unchanged from discharge at 104 bpm; however, she was noted to be hypotensive with a blood pressure (BP) of 86/44 mmHg and oxygen saturation 98% on 3 l. She received multiple fluid boluses in the emergency department and while her HR remained elevated at 104 bpm, her BP increased to 124/79 mmHg. A computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and intravenous contrast was obtained and demonstrated a large mixed attenuation fluid collection with scattered pockets of air within the splenic capsule without evidence of free intra-peritoneal air (Fig. 1). Upon laboratory analysis she was without a leukocytosis and her hemoglobin was decreased; however, unchanged from her previous discharge. It slowly declined throughout her readmission. On post-operative Day 12 her hemoglobin (Hgb) was 7.8, and she received two units of packed red blood cells with an appropriate increase in her Hgb. After initial transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells her hemoglobin and vital signs remained stable.

CT abdomen demonstrating air and fluid contained with the splenic capsule.

An upper gastrointestinal (UGI) contrast study was obtained post-operative Day 2 and repeated upon readmission. Both studies were without evidence of gastrosplenic fistula or anastomotic leak. Follow-up CT scan prior to discharge was without evidence of enlarging fluid collection. She was given instructions about when to return to the emergency room as well as to avoid any trauma to her abdomen. With a stable hemoglobin and minimal abdominal pain, she was once again deemed stable for discharge and instructed to resume her Plavix in 3 days.

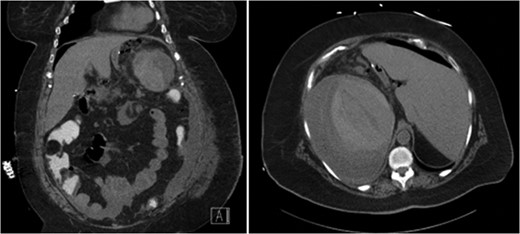

Unfortunately, she presented once more, 20 days after the initial operation with symptomatic hypotension and complaints of severe left upper quadrant pain after a fall in her home. CT scan demonstrated extravasation of intravenous contrast into the peritoneum as well as free intra-peritoneal air (Fig. 2). Given her hemodynamic instability and splenic injury, she was immediately taken to the operating room and underwent an open splenectomy. At the time of splenectomy, only old clotted blood was noted without evidence of purulent fluid or infection. She had a prolonged hospital course but was eventually discharged to a rehabilitation facility.

CT abdomen demonstrating extravasation of contrast and free intra-peritoneal air, with the absence of subcapsular air.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, there are a few case reports indicating splenic thrombosis and iatrogenic capsular tears following bariatric surgical procedures; however, there are no documented cases of subcapsular splenic hematoma and concomitant subcapsular gas collection following laparoscopic SG. The source of the subcapsular gas was concerning, given the uncertainty regarding its origin. Elucidating the source of the gas would help guide our management. The primary concern was abscess or gastrosplenic fistula, both of which were ruled out with physical exam, laboratory analysis and a negative UGI, respectively. Moreover, pathology at time of splenectomy did not reveal any evidence of infection, nor was there any intra-operative findings suggestive of an abscess. On initial imaging, the gas was isolated to the left upper quadrant within the splenic capsule; however, on subsequent imaging at the time of rupture the gas was noted to be freely intra-peritoneal.

Carbon dioxide gas is easily reabsorbed through the parietal peritoneum following laparoscopic procedures. Some studies have documented that carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum resolves within 3 days in 81% of patients and within 7 days in 96% of patients following laparoscopic procedures [5]. We believe that the gas was unable to be reabsorbed as it was trapped within the splenic capsule and, therefore, still present at representation more than 7 days after the initial procedure. The residual pneumoperitoneum can further dissect the capsule from the splenic pulp resulting in trapped gas once the capsule heals. Subcapsular hematomas appear as a low attenuation between the capsule and parenchyma, compressing the parenchyma beneath, allowing differentiation from free intra-peritoneal fluid [6]. In our case, the parenchyma, surrounding hematoma and gas can all be visualized within the splenic capsule. In addition, air could only by visualized within the splenic capsule as there was no noted free intra-peritoneal air or fluid.

We propose that the source of the subcapsular gas was from the pneumoperitoneum. We further propose that the disruption of the splenic capsule allowed air from the pneumoperitoneum to invade beneath the splenic capsule. With the use of the LigaSure™ and Surgicel®, the bleeding from the pulp of the spleen was controlled. However, the capsule was still disrupted, allowing the residual pneumoperitoneum to auto-dissect the splenic capsule from the pulp along the path of least resistance. Continued auto-dissection resulted in expansion of the hematoma and enlargement of the subcapsular gas collection.

Given that the known capsular injury, worsening splenic hematoma secondary to air auto-dissection from pneumoperitoneum is the most plausible explanation of injury. Although, capsular injury is typically benign, in the presence of pneumoperitoneum capsular injury may continue to progress and patients should be monitored closely. Attempted non-operative management is reasonable to preserve splenic function in hemodynamically stable patients; however, progression of injury or hemodynamic instability should prompt early surgical intervention.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.