-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gaurav Sharma, Jonathan A. Schouten, Kamal M. F. Itani, Repair of a bowel-containing, scrotal hernia with incarceration contributed by femorofemoral bypass graft, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 1, January 2017, rjw228, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw228

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The rising use of endovascular techniques utilizing femoral artery access may increase the frequency with which surgeons face the challenge of hernia repair in reoperative groins—which may or may not include a vascular graft. We present a case where a vascular graft contributed to an acute presentation and complicated dissection, and review the literature. A 67-year-old man who had undergone prior endovascular aneurysm repair via open bilateral femoral artery access and concomitant prosthetic femorofemoral bypass, presented with an incarcerated, scrotal inguinal hernia. The graft with its associated fibrosis contributed to the incarceration by compressing the inguinal ring. Repair was undertaken via an open, anterior approach with tension-free, Lichtenstein herniorraphy after releasing graft-associated fibrosis. Repair of groin hernias in this complex setting requires careful surgical planning, preparation for potential vascular reconstruction and meticulous technique to avoid bowel injury in the face of a vascular conduit and mesh.

INTRODUCTION

Femoral artery access for increasingly prevalent endovascular techniques and the association of certain vascular disorders (e.g. aneurysmal degeneration of the aorta) with inguinal hernias is likely to increase the frequency with which surgeons must perform herniorraphy in reoperative groins [1, 2]. This situation is further complicated when a vascular graft has been placed and passes through the field required for hernia repair. Injury or contamination of vascular grafts can result in significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in a patient population with significant cardiovascular comorbidities [3, 4]. We present our experience with this challenging surgical scenario in this report, and review the literature on repair in this setting.

CASE REPORT

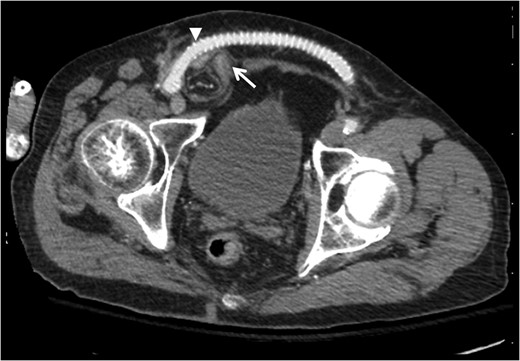

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography axial image demonstrating relationship of bowel-containing inguinal hernia (arrow) with femorofemoral PTFE graft compressing the area of the internal ring (arrowhead).

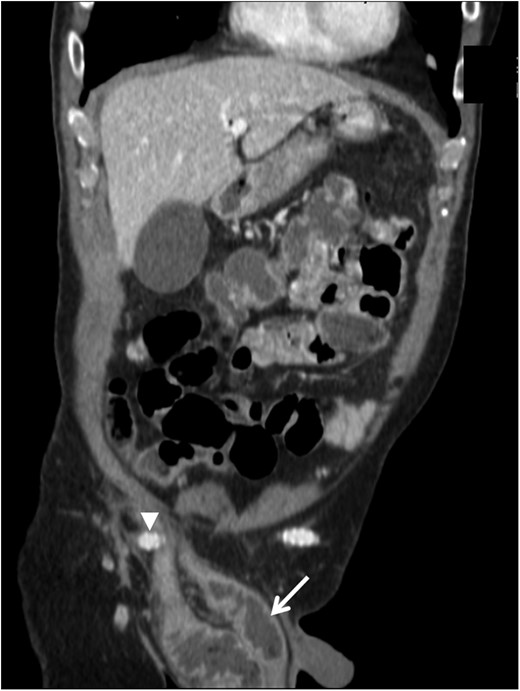

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography coronal image demonstrating the right femorofemoral anastomosis and graft (arrowhead) overlying the hernia sac at the internal ring, with dilated loops of bowel in the hernia sac within the scrotum (arrow).

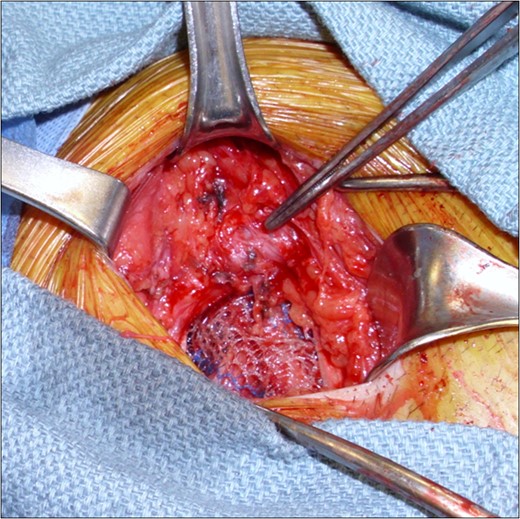

Intraoperative images demonstrating the ringed PTFE graft (tip of forceps) and the tension-free mesh herniorraphy. The external oblique aponeurosis was subsequently closed to provide a layer of separation between mesh and graft.

The patient had an unremarkable recovery. He was ambulating 4 h after surgery and returned to his assisted living facility on the third postoperative day.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the case of a patient presenting with a large incarcerated scrotal hernia. A prior vascular graft with its associated fibrosis had compressed the area of the internal inguinal ring, and adhered to the sac thus contributing to the incarceration. Repair was performed via an open anterior approach and required contingency planning for possible vascular reconstruction, as well as meticulous dissection in order to separate the sac from the graft and release the fibrosis.

The association between hernias and aneurysmal disease has long been reported. The incidence of inguinal hernia in patients scheduled for aortic aneurysm repair has been as high as 41% in some series, with 2.3-fold increased risk of inguinal hernia when compared with patients undergoing surgery for aortoiliac occlusive disease [1, 5–7]. In addition, the frequency of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) for the treatment of unruptured and even ruptured aortic aneurysms has sharply increased [2]. EVAR frequently involves femoral artery cutdown for device access. These factors combined may mean that hernia surgeons will be increasingly faced with the prospect of inguinal hernia repair in a reoperative field in this patient population with a high prevalence of comorbid cardiovascular conditions. Thus, preparation for this clinical scenario and an understanding of principles of repair in this setting are critical for practicing surgeons.

We were faced by precisely this situation in our patient, who developed an incarcerated inguinal hernia following EVAR via open femoral artery access and concomitant femorofemoral bypass grafting due to an occluded iliac arterial system. The development of an incarcerated hernia requiring bowel resection after EVAR has been reported, although the details of hernia location and EVAR approach (vis-à-vis open versus percutaneous) were not provided [8]. To our knowledge, partial or total occlusion of the internal ring by a vascular graft and adhesion of the sac to the graft preventing reduction of an inguinal hernia has not been previously reported. Bowel perforation can have dire consequences in this patient population, particularly if vascular prostheses are secondarily infected.

There is little in the existing English language literature to guide the surgeon's approach to this clinical and anatomic challenge. Utilization of laparoscopic repair or a hybrid laparoscopic and open Lichtenstein mesh herniorraphy have previously been reported when unilateral or bilateral inguinal hernias occur in patients with a prosthetic femoral bypass graft [9, 10]. However, in these cases, the hernia sacs were small relative to the one we encountered (a bowel-containing hernia extending into the scrotum) and thus were amenable to the laparoscopic approach. In our patient, the sac and bowel here were constricted by partial occlusion of the internal ring and adhesion of the sac to the graft, further precluding laparoscopic repair.

In conclusion, repair of groin hernias following prior vascular surgical procedures involving femoral artery dissection with or without placement of a prosthetic represents a surgical challenge. Principles, we would advocate include (i) preoperative imaging to facilitate surgical planning, (ii) preoperative optimization when permitted by the urgency of the clinical situation, given the prevalence of serious cardiovascular comorbidities in this patient population, (iii) use of the laparoscopic approach when possible, to circumvent the anterior, reoperative field, (iv) preparation for vascular reconstruction, including sterile preparation of the contralateral groin, thigh and lower abdomen for bilateral iliofemoral artery access and autogenous venous harvest, as well as preoperative consultation of a vascular surgeon depending on the operating surgeon's comfort performing vascular surgical procedures, (v) cautious mobilization of the vascular graft with an understanding of the anastomotic fixation points and (vi) fastidious technique to avoid entry into the hernia sac and/or bowel injury given the grave consequences of vascular prosthetic graft infection and superior outcomes of hernia repair with nonabsorbable mesh placement.

REFERENCES

- conduit implant

- repair of aneurysm

- fibrosis

- tissue dissection

- hernia, inguinal

- intestines

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- surgical mesh

- surgical procedures, operative

- tissue transplants

- scrotum

- stent/grafts, vascular

- hernia repair

- femorofemoral bypass

- intestinal injuries

- scrotal hernia

- prostheses

- femoral arterial access