-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emma J. Molena, Ashwin Krishnamoorthy, Coimbatore Praveen, SVC obstruction and stridor relieved by nasogastric tube insertion, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 3, March 2016, rjw022, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw022

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Achalasia is an idiopathic motility disorder of the oesophagus of increasing incidence. It is characterized by aperistalsis of the lower oesophagus and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Patients classically present with chronic symptoms of dysphagia, chest pain, weight loss and regurgitation, and they commonly suffer pulmonary complications such as recurrent microaspiration of static, retained food contents of the upper oesophagus. However, it has also been described, uncommonly, to present with megaoesophagus and secondary tracheal compression. We present a case of megaoesophagus secondary to achalasia which presented with stridor and signs of acute superior vena caval obstruction.

INTRODUCTION

Achalasia is a motility disorder of the oesophagus. It has rarely been described to cause megaoesophagus, the exact pathophysiology of which is not known for certain. In cases of megaoesophagus, the enlarged oesophagus causes tracheal compression and respiratory distress. It has also previously been described in one case to cause thoracic inlet compression with engorged neck veins and bilateral neck swelling [1]. The key to management is recognition and urgent decompression of the oesophagus with nasogastric tube.

CASE REPORT

An 81-year-old woman with a background of asthma, ischaemic heart disease and achalasia presented to hospital with a 2-h history of worsening shortness of breath. On examination, she was in visible respiratory distress and was tachypnoeic at 24 breaths per minute, with oxygen saturations of 93% on room air. Examination of the chest revealed diffuse bilateral wheeze. She was tachycardic at 130 beats per minute and hypotensive. There was no specific trigger apart from the patient eating her lunchtime meal. She was also noted to have noisy inspiratory stridor. Furthermore, she had bilateral neck swelling which moved with expiration, and her neck veins were visibly distended. High-flow oxygen was administered, and an arterial blood gas revealed a respiratory acidosis with pH 7.19, p02 15.7 (on 15 l of oxygen), PC02 8.6 and a lactate of 2.9. A provisional differential diagnosis of infective exacerbation of asthma was made with stridor of unknown cause. She was given intravenous fluids and nebulized steroids, intravenous steroid and nebulized adrenaline.

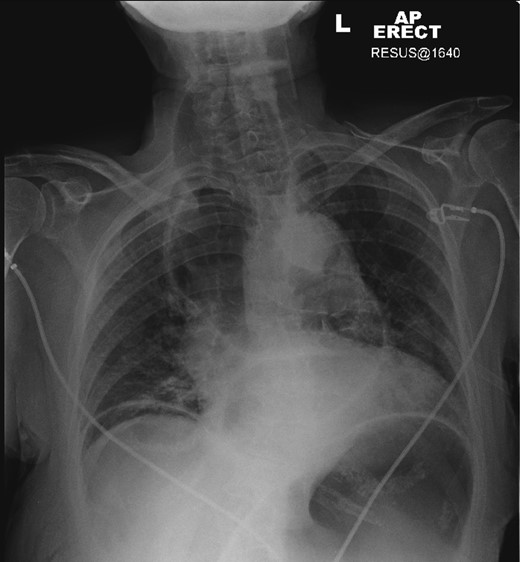

A plain chest radiograph was taken demonstrating a massively dilated air and fluid-filled oesophagus, with no visible intraparenchymal lung abnormality. A 16-French gauge nasogastric tube was immediately placed into the oesophagus with aspiration of air, fluid and food debris. This resulted in almost immediate relief of the patient's respiratory distress, and she clinically improved.

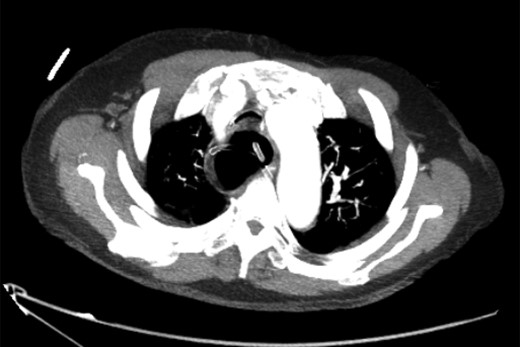

After decompression of the oesophagus, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest confirmed the diagnosis of megaoesophagus causing tracheal compression. The patient, now stabilized, was referred for oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) with a view to Botulinum toxin treatment for underlying achalasia (Figures 1–3).

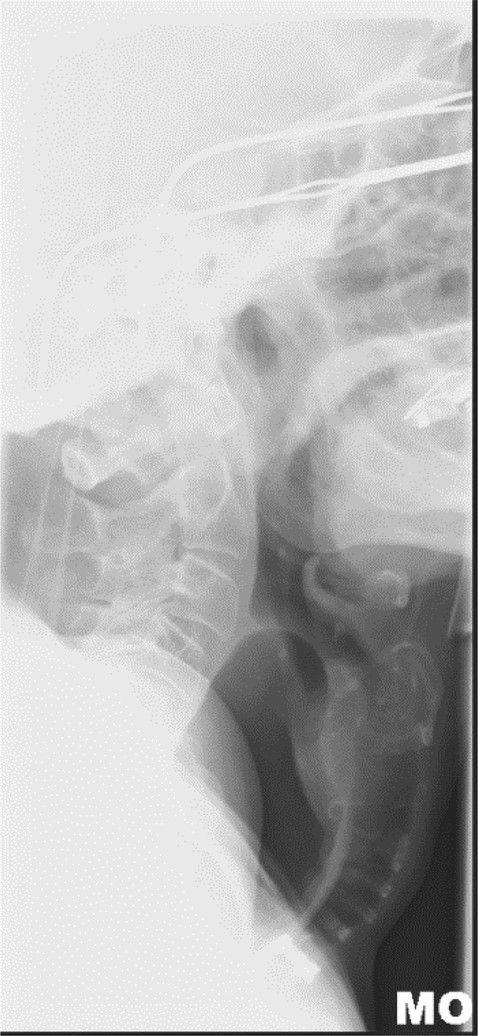

Lateral neck X-ray showing dilated oesophagus displacing trachea anteriorly.

Axial slice of CT chest after nasogastric decompression showing persistent megaoesophagus and airway narrowing.

DISCUSSION

Over 50 years ago, the first instance of achalasia presenting in such fashion was first described [1], and since then, it has been sporadically reported in the literature. These cases have often had similar presentations, typically an elderly woman presenting with sudden onset of respiratory distress, stridor after a meal; with quick relief of symptoms after oesophageal decompression by a nasogastric tube [2–10].

Different hypotheses for the pathophysiology of this presentation have been postulated.

Firstly, it is proposed that the dilated oesophagus is cephalically displaced against the cricopharyngeus muscle resulting in a ‘pinch-cock’, one-way valve system allowing air to enter the thoracic oesophagus but not to escape.

Secondly, results of pharyngeal and upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) manometry have shown repetitive UOS contractions, increased residual UOS pressure and failure of relaxation of the UOS. It is postulated that acute fierce UOS contraction could lead to a one-way valve system resulting in air trapped in a dilated oesophagus as above.

In both instances, the normal belch reflex is lost and the enlarged oesophagus compresses the trachea retrosternally causing airway compromise. A case described in 1976 by McLean et al. reports similar engorged neck veins, facial swelling and bilateral neck swelling indicative of thoracic inlet obstruction [1]. This high intrathoracic pressure results in reduced venous return to the heart and, by Starling's law, reduced cardiac output and hence a haemodynamically unstable patient.

Regardless of the pathophysiology, we advocate that the emergency management should remain the same—achievement of urgent oesophageal decompression. The most effective way to achieve this is insertion of a large-bore nasogastric tube, coupled with suctioning of the upper respiratory tract. Other methods including needle aspiration of the oesophagus, bougienage and oesophagoscopy with catheter insertion have also been described.

In conclusion, doctors must be aware of this rare but potentially fatal acute complication of achalasia as, if managed correctly, a severely ill patient can be quickly and effectively stabilized before referral for definitive management.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.