-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Benjamin C Norton, Ian Robertson, Hui Fan, Rula Najim, Yaman Altal, Ann Sandison, David Hrouda, Massive seminoma presenting with inguinal lymph node metastases only, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 11, November 2016, rjw177, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw177

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

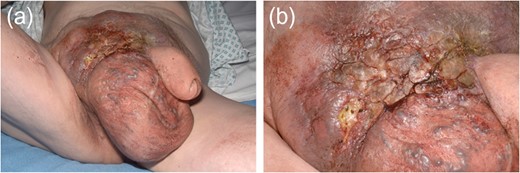

Seminomatous germ cell tumours characteristically affect men in their second-to-fourth decades, presenting as a testicular mass. Metastases when present are usually seen in para-aortic lymph nodes. These tumours are difficult to diagnose clinically and histologically when the presentation is unusual. We describe a seminoma presenting in a 61-year-old male as an inguinal mass with associated lymphadenopathy resembling lymphoma. Past medical history included ipsilateral cryptorchidism and orchidopexy. The tumour responded well to conventional chemotherapy.

This case illustrates a possible diagnostic pitfall and that germ cell tumours should be included in the differential diagnosis of tumours presenting in the groin.

INTRODUCTION

Testicular tumours account for approximately 1% of all malignancies in men [1]. Up to 95% of testicular tumours are germ cell tumours (GCTs), which are subdivided into seminomatous and non-seminomatous tumours [2]. Histologically, seminomas may be further divided into three subtypes: classic, anaplastic and spermatocytic. Pure seminomas do not produce a specific tumour marker subset, but by definition have low levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and can have normal or mildly elevated beta-HCG (beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin) [3]. Risk factors for the development of GCTs include cryptorchidism, Klinefelter's syndrome and testicular dysgenesis [4]. Testicular tumours commonly metastasize along gonadal vessels to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes [5]. Inguinal metastasis from a testicular seminoma is rare and likely related to previous inguinal or scrotal surgery causing disruption in normal lymphatic drainage [6]. We report a case of a massive seminoma presenting with primary inguinal lymph node metastasis in the absence of retroperitoneal lymphatic spread.

CASE REPORT

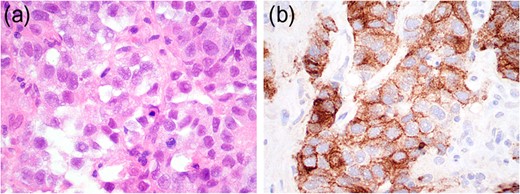

Histopathological and immunohistochemistry findings consistent with seminoma.

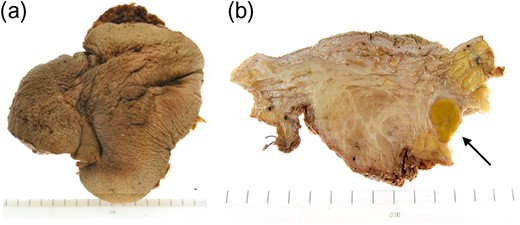

Macroscopic appearance of right testis with scrotal skin and pelvic lymph nodes following right inguinal orchidectomy.

DISCUSSION

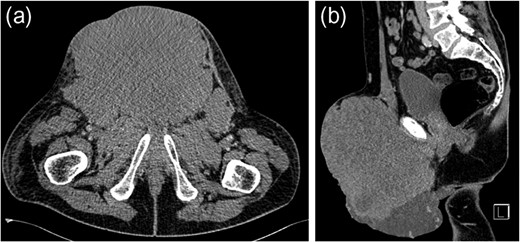

Testicular tumours account for approximately 1% of all malignancies in men, and they are the most common solid malignancy that affect males between 15 and 35 years old [2]. Up to 95% of testicular cancers are GCTs and the most common site for metastatic spread is the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Inguinal lymph node metastasis is a rare occurrence and may be secondary to retrograde extension from significant retroperitoneal metastatic burden [5]. Primary involvement of inguinal nodes may be due to direct tumour invasion into the epididymis, breaching the scrotal wall or extension towards the vas deferens [7]. The large size of the tumour in our case suggests it is highly likely inguinal node involvement was via this route.

However, inguinal metastases have been reported in up to 10% of patients with a testicular tumour who have previously undergone orchidopexy or scrotal surgery [8]. It has been suggested that previous inguinal or scrotal surgery may lead to alteration in the usual patterns of lymphatic drainage. In our case, the history of orchidopexy for cryptorchidism could have been a significant factor for the absence of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy despite the significant tumour burden at presentation. The overall risk of developing testicular cancer is greater in patients with previous cryptorchidism, occurring in 10% of GCTs [9]. Our case suggests that patients who have previously undergone inguinal or scrotal surgery may have alterations in normal lymphatic drainage leading to rare and atypical presentation of metastatic disease despite high tumour burden.

Ultimately, inguinal lymph node metastasis is a rare direction of spread for seminomatous GCTs. It may be secondary to direct extension of the tumour or alteration in the lymphatic drainage after previous inguinal or scrotal surgery. Although retroperitoneal lymph nodes are the most common site of metastasis in GCTs, alternative directions of spread should be considered in those patients who have undergone previous orchidopexy. Extensive imaging beyond CT for initial evaluation of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy is unnecessary.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors helped in writing the article. Norton B. supplied the clinical images. Sandison A. supplied the histopathology images. All authors have read and approved the final article.

INFORMED CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was collected from the patient authorizing the use and disclosure of their protected health information.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All the authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.