-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S. Honeybul, Cerebral metastases from Merkel cell carcinoma: long-term survival, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 10, October 2016, rjw165, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw165

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumour that is locally aggressive. In most cases the primary treatment is local surgical excision; however, there is a high incidence recurrence both local and distant. Cerebral metastases from Merkel cell carcinoma are extremely uncommon with only 12 cases published in the literature. This case is particularly unusual in that, not only was no established primary lesion identified, but also the patient has survived for 10 years following initial diagnosis and for 9 years following excision of a single brain metastasis.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumour that is locally aggressive and has potential for metastatic spread. It was originally described in 1972 by Toker as a sweat gland variant and has become so named because of the discovery of membrane bound dense core neurosecretory granules similar to those found in the normal merkel cell, a neuroendocrine cell of the skin [1].

Given the limited number of published series, there is currently no consensus regarding optimal therapeutic approach [2, 3]. The principal treatment is surgical excision; however, the clinical behaviour is characterized by a high incidence of local recurrence, lymph node involvement and distant metastases [2, 3]. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy have limited impact on overall survival and the prognosis for those patients with progressive disease is poor [3]. The incidence of disease related death ranges from 35% to almost 50% [2, 3].

Cerebral metastases from Merkel cell carcinoma are extremely uncommon with only 12 cases published in the literature. This case is particularly unusual in that, not only was no established primary lesion identified, but also the patient has survived for 10 years following initial presentation and for 9 years following excision of a single brain metastasis.

Case Report

In June 2006 a 65-year-old male presented with a 10 cm mass in the right axilla. This had been present for several months but had recently increased in size. There were no primary skin lesions. Initially he underwent fine needle aspiration cytology and then an axillary clearance. Histopathological examination showed metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma in three out of nine lymph nodes. The tumour cells showed positive immunohistochemical staining for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, chromogranin and CD56. There was perinuclear dot-like positivity for cytokeratin 20 and the overall findings were consistent with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. He was extensively investigated but there was no clinical or radiological evidence of a primary source. He had local radiotherapy at a dose of 50.8 Gy in 28 fractions to the right axilla and supraclavicular fossa over a 6-week period followed by systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide.

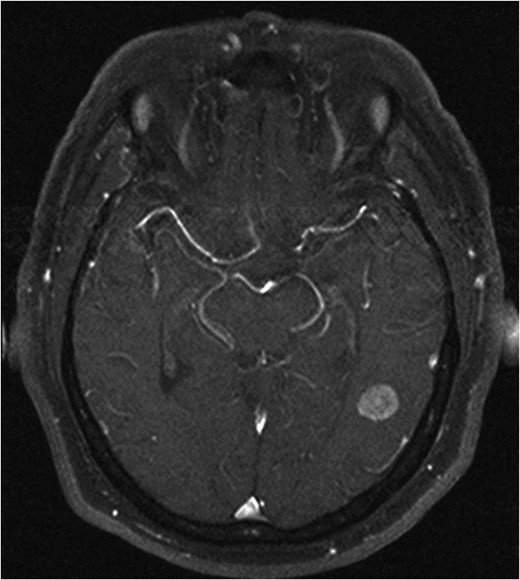

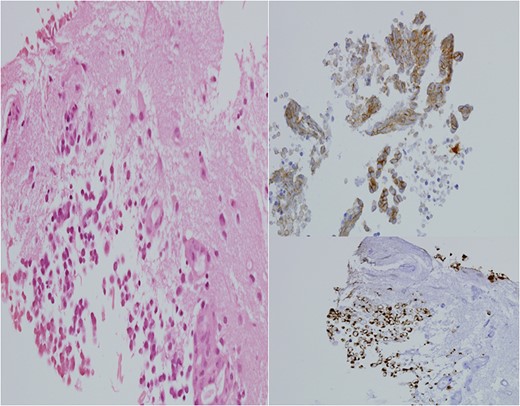

He made an uneventful recovery but presented 1 year later with intermittent dysphasia and confusion. MRI of the brain revealed a homogeneously enhancing lesion in the left posterior temporal lobe (Fig. 1). Staging CT scans identified no other lesions and this was felt to be an isolated metastasis. The patient had a craniotomy and excision of the tumour. Histopathology confirmed a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma with an identical immunohistochemical profile consistent with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (Fig. 2).

H&E stain for brain tissue, left. Immuno-stain for CK20, bottom right. Immuno-stain for CD56, upper right. ×400 magnification.

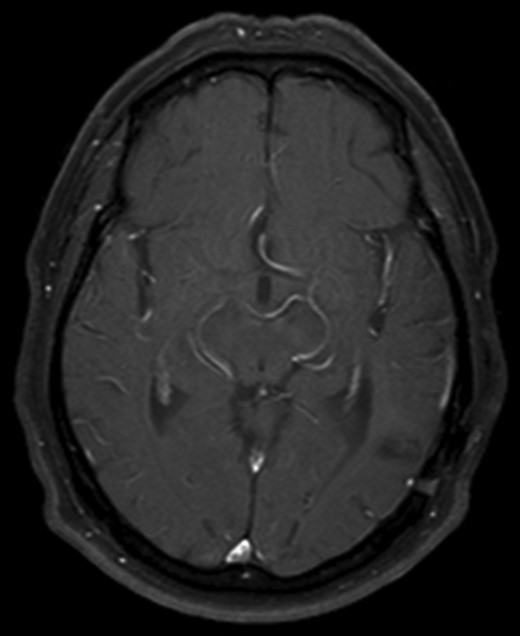

After recovering from surgery the patient had a course of whole brain radiation therapy (30 Gy). He remains well at 10 years following initial presentation, with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence (Fig. 3).

Axial T1 with Gadolinium MRI showing no evidence of recurrence at 10-year follow-up.

Discussion

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous, neuroendocrine tumour, which is locally aggressive and has the potential for metastatic spread [3]. While the incidence has been reported to be increasing, it is still a relatively rare tumour [2]. It predominantly affects elderly Caucasians with a male predominance and it most commonly arises on sun exposed areas of the head and neck region (40.6%) with lesions in the extremities and trunk representing 33% and 23% of cases, respectively [2, 3]. In some cases no primary lesion can be identified [3, 4].

The most consistent prognostic factor associated with survival is the stage of the disease at presentation [5]. Investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre identified tumour diameter as an independent predictor of survival and developed a 4 tiered staging system in 1999. The more recently modified 4 tiered system separates patients with localized and distant disease. Stage I (primary tumour <2 cm); Stage II (primary tumour >2 cm diameter); Stage III (patients with regional disease) and Stage IV (patients with distant disease) [5]. Around 70% of patients present with Stage I or II disease, 25% have loco-regional lymph node involvement and 5% present with Stage IV [3, 6, 7].

Because of its aggressive clinical behaviour, the treatment of choice is wide surgical excision of the primary tumour with adjuvant radiotherapy to control local disease [3]. Chemotherapy is generally reserved for Stage III disease. Despite these treatment regimes outcome can be poor especially for Stage III and Stage IV disease [3, 4]. Allen reported their single institution 5-year survival rates for Stage I—81%, Stage II–67%, Stage III—52% and Stage IV—11% [6].

When considering all types of isolated brain metastases, surgical resection can give better results than radiotherapy alone in cases where the lesion is accessible and causing either neurological symptoms or significant mass effect. A number of studies have demonstrated that patients with a good preoperative level of function and well-controlled systemic disease have improved survival, longer functional independence and a better quality of life than similar patients treated with radiotherapy alone [8–10].

Interpreting these studies in relation to merkel cell tumours has its limitations as there have been only 12 cases reported [4, 11–21]. Of these, one case advocated for aggressive chemotherapy and radiotherapy with curative intent resulting in marginal prolongation of survival [19]. A similar management strategy was supported by Ikawa, with the addition of surgical resection in combination with radiotherapy and chemotherapy; however, this lead to survival of only 11 months [15]. Unfortunately, most cases with brain metastases have been treated with palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy and overall survival has been poor.

The question still remains as to why our particular patient has survived for so long.

The lack of a known primary tumour may be of some relevance. While MCC presenting with lymph node metastases and an unknown primary is a rare occurrence it is well reported [3, 4], and two possible hypotheses have been suggested: firstly, spontaneous regression of the primary lesion and secondly, primary nodal localization of MCC [7].

While the complete spontaneous regression is very rare it is well documented [22] and it has been suggested to be due to an immune reaction induced by biopsy [3, 22]. Whether this may be responsible for the prolonged survival in this case and in other cases of spontaneous remission is currently unknown; however, there are certainly unanswered questions regarding immunological aspects of this cancer.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.