-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anders Mark Christensen, Mads Mark Christensen, Abdominal wall abscess containing gallstones as a late complication to laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 17 years earlier, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 1, January 2013, rjs038, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjs038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the preferred surgical treatment for symptomatic gallstones. The laparoscopic procedure is superior to the open approach in many aspects. Intraperitoneal spillage of bile and gallstones is one of the most common accidental occurrences of LC. We present a case of a 53-year-old woman who developed two abscesses—one intra-abdominally and one in the abdominal wall—17 years after an LC. Three gallstones were found during surgical excision of the abdominal wall abscess. Surgeons should strive to avoid perforation of the gall bladder during LC. If spillage is inevitable attempts should be made to laparoscopically extract as many stones as possible. Documentation of (suspected) spillage is paramount when evaluating the possibility of postoperative complications, even many years later.

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after its introduction in the 1980s, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) became the surgical treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstones.

The laparoscopic approach has clear advantages over open cholecystectomy: postoperative pain is diminished, the cosmetic results are preferable and the patients recuperate sooner and are therefore admitted for a shorter period of time [1–5].

Owing to the inherent technical difficulty associated with laparoscopic surgery bile duct injury and perforation of the gall bladder with bile and gallstone spillage are the most common accidental occurrences of LC [2–10].

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old woman presented to the surgical department with uncharacteristic rectal pain. Upon physical inspection, scars from an LC performed 17 years earlier were noted. Physical examination of the abdomen was normal, but rectal exploration revealed a 7 × 7 cm big impression profound to the anterior rectal wall 5 cm above the external sphincter.

Besides a feeling of heaviness, incomplete defecation and rectal pain, she had no subjective complaints. Temperature at admission was 38°C (100.4°F).

Laboratory tests at admission indicated infection with C-reactive protein of 281 mg/l, leukocytosis of 10.5 × 109/l with 7.6 × 109/l neutrophils.

There was no previous history of inflammatory bowel disease and a recently diagnosed type I diabetes was the only competing illness. Review of the operation notes from the LC revealed that gallstones had been left intra-abdominally since a strongly adherent gall bladder perforated during dissection from the liver bed.

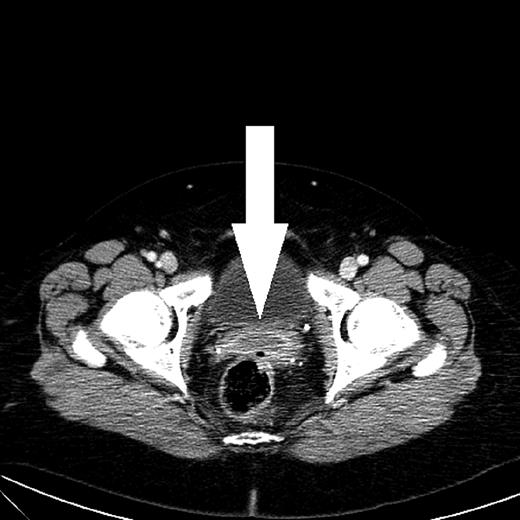

A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 2.7 cm wide abscess in the Douglas pouch (Fig. 1). Anoscopy showed no rectal communication or other anorectal pathology and the abscess was drained transvaginally. Microbiological testing was positive for Enterococcus faecalis.

CT scan shows an abscess with peripheral rim enhancement in the Douglas pouch.

Colonoscopy and gynecological examination were without abnormal findings.

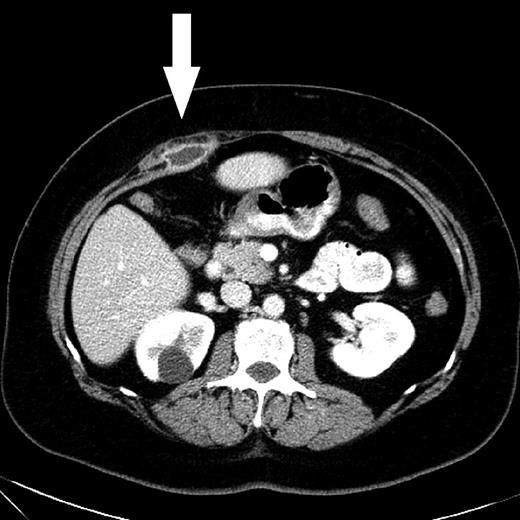

A control CT scan 3 months after the initial admission showed complete regression of the pelvic abscess. Furthermore, a 2 × 3 cm abdominal wall abscess was found behind the superior part of the right rectus abdominis muscle, equivalent to the port site where the perforated gall bladder was extracted 17 years earlier (Fig. 2). Ultrasonically guided biopsy showed acute inflammation and Escherichia coli.

CT scan shows an abscess with peripheral rim enhancement beneath the right rectus abdominis muscle. A simple cyst of the right kidney was a coincidental finding.

The abdominal wall abscess was excised under general anesthesia. Fibrotic tissue along with three gall concrements measuring 3–4 mm were removed.

The postoperative course was uneventful.

DISCUSSION

LC is a procedure associated with low mortality and morbidity. The incidence of gall bladder perforations with spilled bile or gallstones has been found to be as high as 40% (0.1–40%), although complications to retained gallstones are rare, occurring in an estimated 0.08–8.5% [1, 4, 7–9].

The possible manifestations of retained gall stones are diverse, with development of abscesses being one of the most frequent (Table 1). Patients can present with uncharacteristic symptoms many years after LC, although the average temporal dissociation is less than a year [3, 4, 6, 7]. Why some abscesses develop many years after LC in the absence of any known catalyst is still unclarified.

| Article . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Complications . | Estimated complication rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zehetner et al., 2007[8] | Review of 8 studies each with an excess of 500 patients | 24 936 | Intra-abdominal abscesses, abdominal wall abscesses, subhepatic and subphrenic abscesses, fistulas (skin, colocutaneous, colovesical) | 17/10 000 LC |

| Brockmann et al., 2002 [6] | Literature search comprising 91 cases of gallstone spillage | 91 |

| 0.77/ 10 000 LC |

| Sathesh-Kumar et al., 2004 [4] | Review | All possible manifestations secondary to gallstone spillage:

| 8–30/10 000 LC |

| Article . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Complications . | Estimated complication rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zehetner et al., 2007[8] | Review of 8 studies each with an excess of 500 patients | 24 936 | Intra-abdominal abscesses, abdominal wall abscesses, subhepatic and subphrenic abscesses, fistulas (skin, colocutaneous, colovesical) | 17/10 000 LC |

| Brockmann et al., 2002 [6] | Literature search comprising 91 cases of gallstone spillage | 91 |

| 0.77/ 10 000 LC |

| Sathesh-Kumar et al., 2004 [4] | Review | All possible manifestations secondary to gallstone spillage:

| 8–30/10 000 LC |

LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

| Article . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Complications . | Estimated complication rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zehetner et al., 2007[8] | Review of 8 studies each with an excess of 500 patients | 24 936 | Intra-abdominal abscesses, abdominal wall abscesses, subhepatic and subphrenic abscesses, fistulas (skin, colocutaneous, colovesical) | 17/10 000 LC |

| Brockmann et al., 2002 [6] | Literature search comprising 91 cases of gallstone spillage | 91 |

| 0.77/ 10 000 LC |

| Sathesh-Kumar et al., 2004 [4] | Review | All possible manifestations secondary to gallstone spillage:

| 8–30/10 000 LC |

| Article . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Complications . | Estimated complication rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zehetner et al., 2007[8] | Review of 8 studies each with an excess of 500 patients | 24 936 | Intra-abdominal abscesses, abdominal wall abscesses, subhepatic and subphrenic abscesses, fistulas (skin, colocutaneous, colovesical) | 17/10 000 LC |

| Brockmann et al., 2002 [6] | Literature search comprising 91 cases of gallstone spillage | 91 |

| 0.77/ 10 000 LC |

| Sathesh-Kumar et al., 2004 [4] | Review | All possible manifestations secondary to gallstone spillage:

| 8–30/10 000 LC |

LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Perforation of the gall bladder most often occurs during dissection from the liver bed, on retracting the gall bladder with a grasping instrument or on extraction through a port site [2–4, 6, 7, 10]. The risk of perforating the gall bladder when it is subjected to physical strain becomes greater under conditions of acute inflammation [3, 4, 7–9].

Whether spillage of gallstones leads to complications or not depends on several combined factors, e.g. the number and size of stones and the patient's age [6]. The chemical composition of gallstones plays a significant part in the abscess etiology, with pigmented stones being especially prone to harbor bacteria and thereby cause formation of abscesses [2–4, 6, 8, 9]. The bacterial species most often found in the abscesses are those typical of the intestinal flora and often found in cholecystitis, e.g. E. coli and Enterococcus [6, 9].

If gall bladder content is spilled intraoperatively, most surgeons agree on the following general approach [1–10]:

– Retrieve as many stones as possible laparoscopically; lost stones do not warrant a conversion to open surgery.

– Copious irrigation dilutes the irritative bile salts.

– If gallstones are known or suspected to remain intra-abdominally it should be apparent from the operation note.

As a preventive measure to stone loss during extraction, endobags are normally used to contain the gall bladder and possible loose stones [2, 4, 7, 8, 10].

In case of perforation of the gall bladder, the immediate use of a suction device to extract as much gall bladder content as possible can save the surgeon the laborious task of searching for loose intraperitoneal stones [2, 4, 7, 8, 10].

Extension of the port site incision in order to extract the gall bladder intact is a good choice short of risking spillage of gallstones when trying to force the gall bladder through an undersized port site [2, 10].

In the case described, the connection between the patient's symptoms and the causative agent was only made because of a detailed operation note.

The CT scans failed to show gallstones in the two abscesses even though gallstones eventually were found on excision of the abdominal wall abscess. It is not uncommon for gallstones to elude visualization by CT, and ultrasound can be a reasonable supplement in case of superficial abscesses [8].

Stones where not found in the pelvic abscess, but all circumstances point to an etiology, were bile concrements containing E. faecalis have passively migrated to the most decline space in the female abdominal cavity, the Douglas pouch. This hypothesis is supported by Brockmann et al. who reviewed gallstone loss in 47 females, where the most common pelvic location of stones was the Douglas pouch [6]. In the case described, no intestinal or gynecological pathology was found to explain the abscess.

The incidence of complications to unretrieved gallstones is low, but given the broad spectrum of possible complications surgeons should strive to avoid perforating the gall bladder during LC. If spillage is inevitable, attempts should be made to laparoscopically extract all stones.

Certain or suspected lost gallstones retained in the patient after surgery should be documented clearly in the operation report to elucidate future evaluation of possible long-term complications.