-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

R Harries, A Khan, G Whiteley, Spontaneous oesophageal perforations in a competitive swimmer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 8, August 2012, Page 14, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2012.8.14

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Oesophageal perforation is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. We report a case of a young male athlete who presented to our unit with two separate areas of spontaneous oesophageal perforation.

INTRODUCTION

Oesophageal perforation is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that is associated with a reported mortality rate of 18-21% (1,2). Early diagnosis and prompt appropriate intervention are the key to successful outcomes. We report a case of two separate areas of spontaneous oesophageal perforation in a competitive swimmer.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old male competitive swimmer presented as an emergency admission under the Physicians with 6 day history of chest pain and difficulty swallowing, associated with one episode of vomiting 3 days ago. He was normally fit and well, with minimal alcohol intake. On admission he had a tachycardia of 110 bpm and a temperature of 37.9 oC. Cardio-respiratory and abdominal examination was unremarkable. Routine bloods revealed a White Blood Cell Count of 14.9 x 109/L, C-reactive protein of 247mg/L and a Bilirubin of 87 µmol/L. Troponin levels were within normal limits. Urinary dipstick revealed no abnormalities. A chest X-ray was normal.

He was treated as a presumed diagnosis of bilary sepsis with broad spectrum antibiotics and an abdominal ultrasound was performed the following day. Abdominal ultrasound showed normal appearance to liver, pancreas and gallbladder with normal bilary duct system and no evidence of pericholecystic fluid.

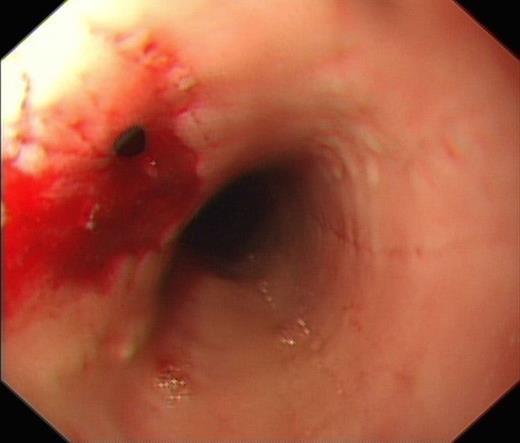

He subsequently underwent an Oesphago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD), which showed 2 separate oesophageal perforations, the first at 25cm from the incisors and the second at 27cm from the incisors. The perforation at 25cm was successfully clipped, however the second perforation at 27cm was deemed too big to clip (Fig. 1 & 2).

OGD showing clipped perforation at 25cm from incisors and further perforation at 27cm from incisors

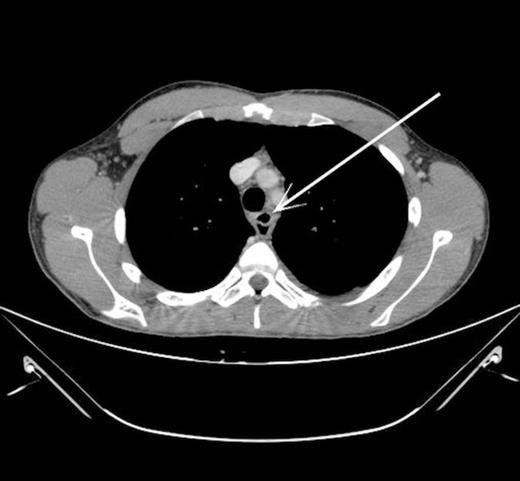

The Surgeons were contacted and a CT thorax and abdomen was requested. A CT thorax and abdomen showed a small (7mm x 5mm) air pocket anterior to the oesophagus in keeping with an isolated perforation. There was no evidence of pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum or fluid collection (Fig. 3).

CT thorax showing pocket of air anterior to oesophagus (indicated by arrow)

The On-call Upper Gastrointestinal Consultant Surgeon was contacted and the decision was made for conservative management. The patient had a peripherally inserted central line (PICC) inserted, was made ‘nil by mouth’ and commenced on Total Perenteral Nutrition (TPN) and Intravenous Imipenem, Metronidazole and Caspofungin.

Six days later a Water soluble contrast swallow study was performed and confirmed that there was no residual leak from the oesophagus. He was commenced on normal diet, weaned of TPN and discharged home two days later.

DISCUSSION

The aetiology of oesophageal perforation was attributed to iatrogenic causes in up to 52% of cases (3). Previous literature has described the link between external blunt trauma and oesophageal perforation; however this is usually associated with perforation at the level of cervical or upper thoracic oesophagus (4), and never reporting two separate perforations. In this case the level of the two separate perforations was at 25cm and 27cm from the incisors, in a history of competitive swimming. To date there has been no reported cases of oesophageal perforation documented in competitive sportspersons.