-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

D Morison, H Noble, PM Peyser, A case of tension pneumothorax mimicking spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 4, April 2011, Page 4, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.4.4

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 40 year old asthmatic presented with acute respiratory distress. Chest radiograph appeared to show loops of bowel within the thorax and a diagnosis of spontaneous/effort rupture of the diaphragm was made. Emergency laparotomy revealed an intact diaphragm and chest drain was inserted relieving a tension pneumothorax.

INTRODUCTION

This case of tension pneumothorax mimicking a spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm highlights the clinical and radiographic similarities between these two conditions and the potential difficulty in making the correct clinical diagnosis.

CASE PRESENTATION

A forty year old gentleman was admitted to the intensive care unit via the emergency department in extremis with severe type II respiratory failure. He had a past medical history of asthma and at the time no other history was available. On admission his pulse was 115, BP 90/50, RR 32 with a SaO2 of 65% and CO2 of 10 kPa on 10 L O2. On examination he had coarse creps throughout the right lung and reduced air entry left lung. His abdomen was tense with no audible bowel sounds. He was initially supported with non-invasive ventilation with no improvement in his condition and he was, therefore, intubated. His condition continued to rapidly deteriorate on the intensive care unit.

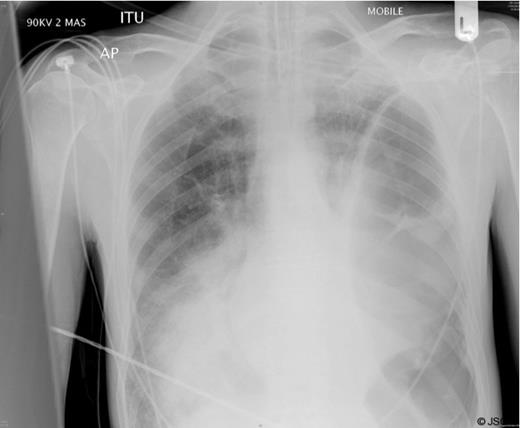

A chest radiograph (Figure 1) showed a large air filled structure within the left hemithorax, loss of clarity of the left hemidiaphragm and patchy consolidation of the middle and right lower lobes.

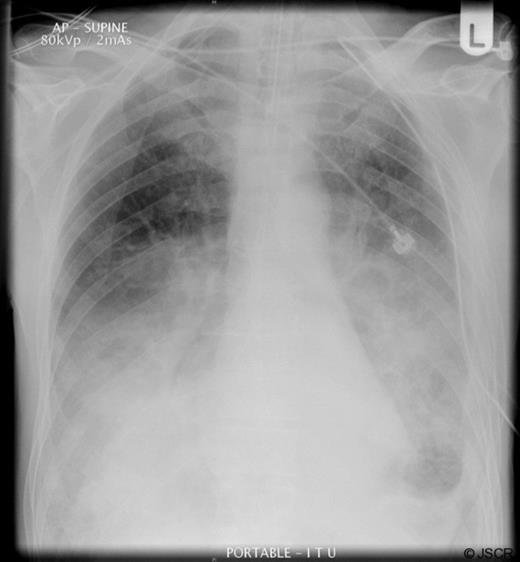

A clinical diagnosis of a possible spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm was made. The patient underwent an emergency laparotomy as he was not stable enough to undergo cross-sectional imaging to confirm the diagnosis. There were no abnormal findings at laparotomy. A left sided chest drain was immediately inserted with release of air under tension and pus (Figure 2).

The patient remained intubated for five days, initially being weaned onto CPAP, and spent ten days in total on the intensive care unit. He developed a small residual empyema on the left side after the chest drain was removed which resolved with an extended course of antibiotics. He spent a total of 6 weeks in hospital before discharge with support at home. At a follow up outpatient appointment two months he remained well.

DISCUSSION

In retrospect it is likely that this gentleman presented with a severe pneumonia complicated by a contained tension pneumothorax within an empyema cavity caused by positive pressure ventilation.

Spontaneous or effort rupture of the diaphragm is a well recognised but rare entity accounting for only 1% of all diaphragmatic ruptures (1). The word “spontaneous” is a contested point among authors, with some feeling that all cases of spontaneous rupture are in fact effort related (2). The exact aetiology of diaphragmatic rupture remains unclear but there is a sudden shift of pressure across the abdomino-thoracic pressure gradient which causes herniation of bowel contents through the diaphragm. In a literature review of 28 detailed reports it was most commonly associated with coughing (32%), intense exercise (21%) and labour (14%) (3). Patients present with pain, dyspnoea, nausea/vomiting and are commonly acutely unwell. The treatment is early laparotomy, return of herniated viscera to the abdomen wand closure of the diaphragmatic defect.

The clinical presentation of a tension pneumothorax is often similar with severe cardio-respiratory compromise and the patient in extremis. It is a well recognised complication of positive pressure ventilation with or without associated lung disease (4). The plain radiographic appearances of these two conditions are also similar with both conditions associated with air filled cavities within the thorax with or without mediastinal shift.

This case highlights the clinical difficulties in separating the diagnosis of these two conditions and demonstrates the importance, in some cases, of immediate surgical intervention in the acutely unwell patient rather than delay for definitive imaging.