-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

KH Hutson, D Sandooram, ML Harries, An unusual case of dysphagia following routine electrical DC cardioversion, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 3, March 2011, Page 7, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.3.7

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Dysphagia can arise from a multitude of underlying pathologies affecting any of the three stages of swallowing; oral, pharyngeal and or oesophageal; and can be further classified as intraluminal, intramural or extramural. We discuss an unusual case of acute dysphagia secondary to haematoma formation within one of a number of potential neck spaces. We report on a novel precipitant; routine electrical cardioversion. A review of relevant anatomical boundaries, symptoms, precipitants and treatment options will be discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Enclosed haematomas of the neck are relatively rare; occurring secondary to often trivial precipitating factors, occasionally with fatal outcomes. A high index of suspicion is required to ensure early diagnosis; minor precipitating events must be carefully elucidated, associated injuries (e.g. fractures) sought and the bleeding tendency of the patient addressed. Regular assessment and imaging allows for early intervention in the case of continued haematoma expansion.

CASE REPORT

A 67 year old gentleman underwent elective DC cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation (AF). He had previously been chemically cardioverted with amiodarone; however reoccurrence of AF with increasing levels of thyroid stimulating hormone had prompted the decision to attempt electrical cardioversion. Warfarin had been initiated during the preceding four months and an international normalised ratio (INR) of 2.5 was recorded on the day of procedure. Following an unsuccessful initial biphasic shock the energy level was escalated from 200 to 360 joules with resulting capture of sinus rhythm. No complications were reported post procedure and he was discharged home after three hours observation.

The patient represented two days later with a 24 hour history of sore throat, hoarse voice and progressive dysphagia. Bruising had slowly developed over his sternum and migrated up his anterior neck; with associated swelling visible over the left anterior neck triangle (Figure.1).

The patient’s anterior chest wall and neck upon initial presentation. Provided by the clinical photography department; Royal Sussex County Hospital; under full patient permission.

His airway was patent and no breathing difficulties were noted. Admission blood tests revealed an INR of 2.6 and haemoglobin of 13.5g/dl. Flexible nasendoscopy demonstrated swelling and bruising of the left aryepiglottic fold and vocal cord; which were hypomobile in comparison to the uninvolved right cord. Computerised tomography (CT) was undertaken on admission and magnetic resonance images (MRI) obtained the next day. A 5×4cm homogenous hypodense mass was visible lying separate and just lateral to the left thyroid lobe; deep to the left strap muscles and anterior to sternocleidomastoid (Figure.2).

Axial CT image demonstrating the left anterior cervical mass (outlined with arrows) and associated contralateral shift of the adjacent airway.

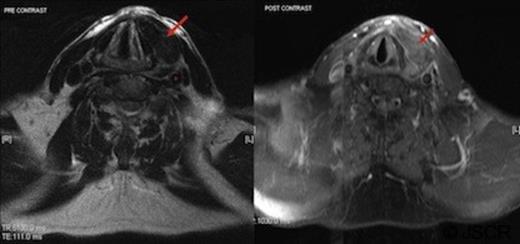

Intravenous gadolinium contrast demonstrated peripheral enhancement of the mass (Figure.3); given the history and preceding cardioversion it was felt the most likely diagnosis was that of a haematoma.

MRI imaging (pre then post contrast) demonstrates enhancement of the left sided mass with gadolinium (arrow); suggesting the presence of blood. The carotid sheath (*) can be seen separately from the mass and is marginally displaced posteriorly.

The patient was monitored for airway compromise and commenced on intravenous dexamethasone and prophylactic antibiotics. It was incidentally noted the patient had reverted to AF; given his stable state and marginally elevated INR cardiology advised to restart digoxin and briefly withhold warfarin until the INR dropped to 2. Both dysphagia and hoarseness significantly improved within 24 hours of starting dexamethasone, which was continued for a total of 48 hours duration. The patient remained clinically well and the neck swelling began to subside. Warfarin was restarted and the patient discharged home after a total stay of four days. An uneventful follow up pursued with complete resolution of symptoms; no subsequent underlying vascular abnormality was identified.

DISCUSSION

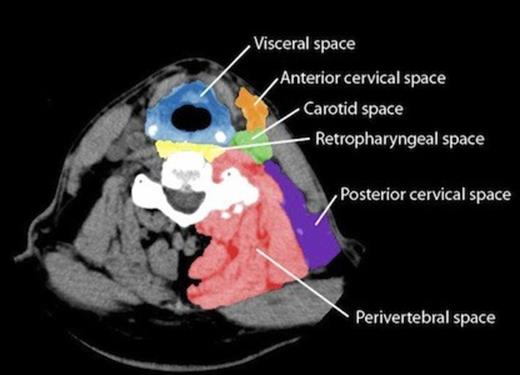

The large mass identified on axial imaging was anatomically located within the left anterior cervical space; the boundaries of which are formed by all three layers of the deep cervical fascia before they converge; forming the carotid sheath posteriorly (1) (Figure. 4).

Digital colouring of potential neck spaces (normal left neck) with respective fascial boundaries.

Enlargement of this enclosed space can cause displacement of the airway to the contra-lateral side. Our working diagnosis was that of a haematoma however differentials include an abscess, lipoma, lymph-node, aneurysm and the possibility of an underlying lesion (tumour/ thyroid). Clinical presentation can be non specific and may occur days after the initial insult. Other reported signs and symptoms include trismus, neck stiffness, bruising, globus, dyspnoea and odynophagia (2).

Neck haematomas most frequently develop post blunt traumatic injury (3); hyperextension injuries with or without associated cervical fractures appears to be an increasing feature (4). Previous reports have described haematoma formation as the result of trivial factors including coughing, straining as well as occurring spontaneously (5). Other precipitating factors include foreign body ingestion (iatrogenic secondary to instrumentation and laryngoscopy), carotid sinus massage (3) and even acupuncture (6). A raised INR is often a cofounding variable.

Treatment relies upon an accurate initial assessment following an ABC approach. The airway requires thorough investigation with a flexible nasendoscope and plain film x-rays can provide an initial evaluation; lateral neck views may demonstrate prevertebral soft tissue swelling and a chest x-ray can provide an estimate to degree of extension (7). CT and MRI provide greater anatomical delineation and subsequent use of contrast allows differentiation of blood from pus. A critically compromised airway will require intubation or tracheostomy placement and theatre may be considered for exploration and surgical evacuation. A conservative approach can be adopted in stable patients with small nonexpanding haematomas; intravenous steroids reduce soft tissue swelling and haematoma resolution can be monitored radiographically. The role for prophylactic antibiotics remains unclear.

We were unable to find any previous reports documenting the development of neck haematomas following DC cardioversion, especially where the INR was found to be within acceptable levels for this procedure. The patient’s anterior chest bruising could plausibly be explained by the cardioversion procedure; we were however unable to clearly identify the underlying reason for developing a neck haematoma. Possible hypotheses include distant trauma sustained during cardioversion itself, bleeding secondary to the raised INR or disruption of an underlying vascular defect; although no obvious vascular abnormality was evident on imaging. Spontaneous neck haematomas are well documented and a previous report by Abaskaron et al (8) described a mediastinal haematoma occurring solely on a background of well controlled oral anticoagulation. Our reported case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in patients presenting with non specific symptoms in whom there is an inherently increased risk of bleeding; be that a raised but acceptable INR.