-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thadei Liganga, Ezekiel Gathii Karuga, Morbid iatrogenic epistaxis in a child with undiagnosed hematological malignancy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 2, February 2026, rjag050, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjag050

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Epistaxis is a common pediatric emergency, usually benign, and self-limiting. However, it may indicate serious underlying disease, particularly hematologic malignancy. In resource-limited settings, delayed diagnosis and inadequate expertise can worsen outcomes, and inappropriate nasal packing may aggravate bleeding in children with unrecognized coagulopathies. This case involves a 6-year-old girl with five days of spontaneous intermittent epistaxis, initially managed with anterior nasal packing that led to worsening hemorrhage and referral. Examination revealed extensive iatrogenic mucosal injuries, while laboratory investigations showed severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis. She was diagnosed with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and later died from uncontrolled gastrointestinal and nasal bleeding despite treatment. The case highlights the need for prompt evaluation of recurrent or severe pediatric epistaxis for potential hematologic malignancy and illustrates the risks posed by unsafe nasal packing and limited diagnostic resources in low-resource healthcare settings.

Introduction

Epistaxis is one of the most common otorhinolaryngology emergencies in children, with most cases being benign and self-limiting [1]. However, recurrent or severe bleeding may serve as an early clinical manifestation of serious systemic disease, including hematologic malignancies such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [2, 3]. The pathophysiology of such bleeding is frequently related to bone marrow suppression leading to thrombocytopenia, impaired platelet function, and reduced production of coagulation factors. Coagulopathy in such patents is also contributed by leukemic infiltration of the mucosa causing fragility, vascular compromise and hence spontaneous or easy bleeding [4]. In many low-resource settings, the diagnostic evaluation of pediatric epistaxis is often delayed due to limited access to complete blood counts, coagulation studies, and specialist consultation. As such, potentially fatal underlying disorders may initially be overlooked, contributing to increased morbidity and mortality.

Iatrogenic nasal trauma is a relatively uncommon cause of epistaxis. Most iatrogenic injuries follow nasal surgery, emergency airway interventions, repeated nasal instrumentation such as insertion of nasogastric tubes and anterior nasal packing. All these carry a risk of mucosal injury and iatrogenic nasal trauma [5, 6]. This risk is increased in patients with coagulopathies, and when they are performed inappropriately, or by an unskilled person. In low-resource settings, limited lighting, inadequate equipment availability, and procedures being performed by less experienced personnel are factors that contribute to avoidable morbidity [7].

Case presentation

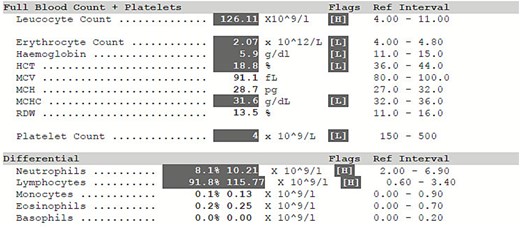

A 6-year-old girl presented with a 5-day history of spontaneous, intermittent epistaxis initially managed at a peripheral health center with anterior nasal packing. Following packing, the bleeding intensified, becoming profuse and soaking the packs, accompanied by oropharyngeal bleeding, prompting urgent referral. On arrival to the emergency department, she appeared lethargic, with blood-soaked nasal gauze secured to the columella and clots around the nares (Fig. 1). Full blood count revealed severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leucocytosis (Fig. 2).

Blood-soaked gauze secured to the columella with blood clots around the nares.

Full blood picture: Severe anemia, massive leucocytosis with lymphocyte predominance and severe thrombocytopenia.

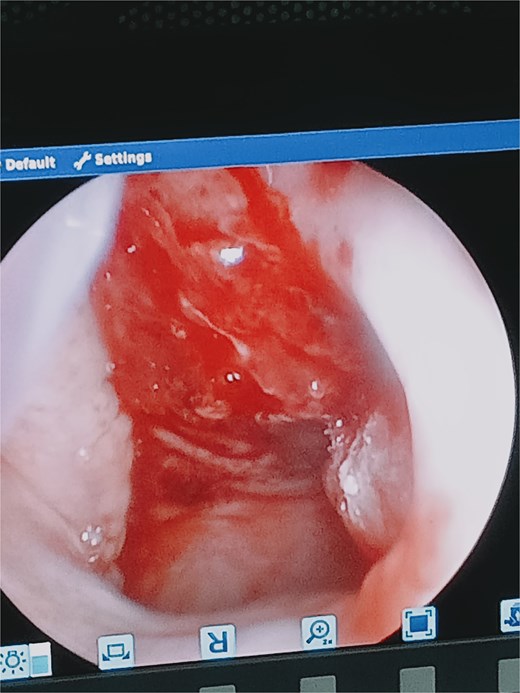

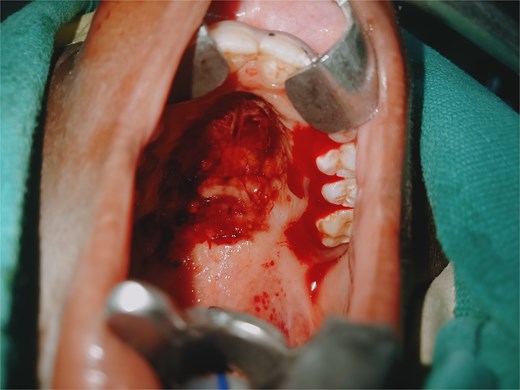

She was taken for examination under anesthesia where nasopharyngoscopy demonstrated extensive mucosal lacerations involving the inferior turbinate, nasal floor, nasopharyngeal roof and posterior wall, with active bleeding (Fig. 3). Additional traumatic injuries were observed on the soft palate and the left posterior tonsillar pillar (Fig. 4). Blood clots were evacuated, through irrigation, and hemostasis was achieved through gauze compression, suturing, and electrocautery, followed by anterior and posterior nasal packing. She received two units of blood and was stabilized before transfer to the pediatric oncology ward.

Nasoendoscopy through the left nostril showing mucosal injury on the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx, with active bleeding.

Oral cavity examination showing actively bleeding lacerations on the soft palate and left tonsillar pillar.

Subsequent investigations confirmed B-cell ALL, for which appropriate therapy was initiated. Despite medical management, multiple transfusions, and chemotherapy, the patient’s condition progressively deteriorated, complicated by recurrent vomiting and uncontrolled gastrointestinal and recurrent nasal bleeding, ultimately resulting in death.

Discussion

Epistaxis may be an early, sometimes the first, clinical presentation of leukemia in children. Multiple studies have reported that mucocutaneous bleeding, including nasal bleeding, gingival hemorrhage, and easy bruising is frequently among the initial symptoms prompting medical attention. In ALL, thrombocytopenia caused by marrow infiltration is the key mechanism driving such bleeding. In the present case, the child’s spontaneous intermittent epistaxis represented an important but under-recognized warning sign of a severe hematologic disorder. Similar cases have been documented in the literature, demonstrating that delays in recognizing hematologic causes of epistaxis can result in late diagnosis and poor outcomes, especially in resource-limited regions [2, 8].

Nasal packing is a common intervention for anterior epistaxis; however, when performed improperly, it can lead to significant iatrogenic injury. Reported complications include mucosal laceration, septal hematoma, posterior pharyngeal trauma, infection, and worsening hemorrhage. The risk is amplified in patients with unrecognized hematologic disorders in whom mucosal fragility and poor coagulation predispose to severe bleeding [6, 9]. In this case, the initial anterior nasal packing performed at a peripheral health center resulted in extensive mucosal trauma across the turbinates, nasal floor, and nasopharynx, exacerbating the bleeding and contributing to hemodynamic compromise. Improperly trained personnel and use of improvised packing materials are major contributors to iatrogenic nasal injuries in low-resource settings [10, 11].

Healthcare centers in low-resource regions face increased limitations in their operation, including availability of trained personnel and advanced equipment which are all required for safe healthcare delivery. Many peripheral facilities lack ENT surgeons, endoscopic equipment, appropriate nasal packing devices, and reliable laboratory services. As a result, clinicians often rely on basic tools and incomplete clinical information when managing epistaxis. Lack of early diagnostic capacity contributes to delayed detection of malignancies such as ALL, while the scarcity of trained personnel increases the likelihood of unsafe procedures and preventable complications. Higher morbidity and mortality has been observed with pediatric hematologic malignancies in low-resource systems due to late presentation, limited specialist care, and inadequate supportive therapy [12–14].

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Thadei Liganga was responsible for conceptualization. Ezekiel Gathii was responsible for data collection and both authors were equally responsible for manuscript drafting and proofing.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

Lukama L, Aldous C, Michelo C et al. Ear, nose and throat (ENT) disease diagnostic error in low-resource health care: observations from a hospital-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE

Tunkel DE, Anne S, Payne SC et al. Clinical practice guideline: nosebleed (epistaxis). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery