-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mariana Treviño Ayala, Luis Ricardo Sánchez Escalante, Allan Méndez Rodríguez, Mauricio Kuri Ayache, Héctor Fernando Sánchez Maldonado, Bilateral renal in situ reimplantation enabling endovascular repair of a complex aortoabdominal aneurysm: a challenging surgical case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 2, February 2026, rjaf1045, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1045

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the case of a 58-year-old male with a complex suprarenal and infrarenal aortoabdominal aneurysm and multiple renal arteries. Due to anatomical constraints that precluded endovascular repair, bilateral renal in situ reimplantation was performed, followed by the successful deployment of a physician-modified endograft. Despite postoperative complications, the patient recovered fully and was discharged in stable condition. This case highlights the feasibility and clinical value of combining open and endovascular techniques in high-risk vascular patients when standard endovascular approaches are not viable.

Introduction

Bilateral renal in situ reimplantation represents a valuable surgical option for the management of complex aortic aneurysms. Although rarely performed due to its technical complexity and inherent risks, it may be the only viable approach in selected clinical scenarios—particularly when anatomical constraints preclude the use of endovascular techniques. This report presents a case of a complex suprarenal and infrarenal aortoabdominal aneurysm associated with an anatomical variation involving three right renal arteries and two left renal arteries, emphasizing the favorable outcomes achieved through bilateral renal artery reimplantation.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old male presented with a 1-year history of chronic left lumbar pain. The pain was described as insidious in onset, stabbing in character, and moderate in intensity, without radiation. It worsened during rest, improved with movement, and was not associated with any additional symptoms. Over the preceding 2 months, the pain had progressively intensified, prompting further evaluation.

On admission, the patient was neurologically intact. Physical examination of the neck revealed a jugular venous pulse measuring 5 cm, with no carotid bruits. Both hemithoraces were well ventilated, and cardiac auscultation revealed regular rhythm with normal heart sounds and no gallops (S3 or S4). Abdominal examination demonstrated preserved peristalsis, a soft and non-distended abdomen, and a palpable, non-tender pulsatile mass in the mesogastrium. A systolic murmur graded IV/VI was auscultated over the mesogastric region. Peripheral vascular assessment revealed diminished distal pedal pulses with a capillary refill time of <2 s. A comprehensive imaging workup confirmed the presence of a complex aortoabdominal aneurysm involving both the suprarenal and infrarenal segments (Figs 1–3). Aneurysm dimensions are detailed in Table 1.

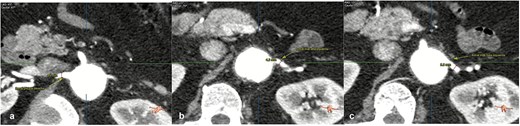

Contrast-enhanced thoraco-abdominal computed tomography (CT) with IVD at superior mesenteric artery level (a), celiac trunk level (b), renal arteries level (c).

Contrast-enhanced thoraco-abdominal CT with dimensions of principal right renal artery (a), most superior left renal artery (b), most inferior left renal artery (c).

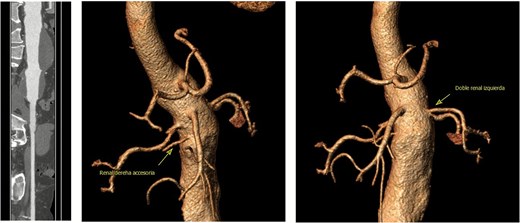

Contrast-enhanced thoraco-abdominal CT scan and angio computed tomography (CTA).

| Aneurysm measurement . | Dimensions (mm) . |

|---|---|

| Maximum diameter of the adrenal aneurysm | 38 × 38 |

| Maximum diameter of the infrarenal aneurysm | 61.8 × 62.8 |

| Diameter at the adrenal level | 34 × 36 |

| Diameter at the infrarenal level | 38 × 38 |

| Diameter at the level of the iliac bifurcation | 50 × 51 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common iliac artery | 11 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common iliac artery | 9 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right external iliac artery | 6.8 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left external iliac artery | 6.9 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common femoral artery | 8.7 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common femoral artery | 8.4 |

| Aneurysm measurement . | Dimensions (mm) . |

|---|---|

| Maximum diameter of the adrenal aneurysm | 38 × 38 |

| Maximum diameter of the infrarenal aneurysm | 61.8 × 62.8 |

| Diameter at the adrenal level | 34 × 36 |

| Diameter at the infrarenal level | 38 × 38 |

| Diameter at the level of the iliac bifurcation | 50 × 51 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common iliac artery | 11 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common iliac artery | 9 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right external iliac artery | 6.8 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left external iliac artery | 6.9 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common femoral artery | 8.7 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common femoral artery | 8.4 |

| Aneurysm measurement . | Dimensions (mm) . |

|---|---|

| Maximum diameter of the adrenal aneurysm | 38 × 38 |

| Maximum diameter of the infrarenal aneurysm | 61.8 × 62.8 |

| Diameter at the adrenal level | 34 × 36 |

| Diameter at the infrarenal level | 38 × 38 |

| Diameter at the level of the iliac bifurcation | 50 × 51 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common iliac artery | 11 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common iliac artery | 9 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right external iliac artery | 6.8 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left external iliac artery | 6.9 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common femoral artery | 8.7 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common femoral artery | 8.4 |

| Aneurysm measurement . | Dimensions (mm) . |

|---|---|

| Maximum diameter of the adrenal aneurysm | 38 × 38 |

| Maximum diameter of the infrarenal aneurysm | 61.8 × 62.8 |

| Diameter at the adrenal level | 34 × 36 |

| Diameter at the infrarenal level | 38 × 38 |

| Diameter at the level of the iliac bifurcation | 50 × 51 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common iliac artery | 11 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common iliac artery | 9 (tortuous path) |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right external iliac artery | 6.8 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left external iliac artery | 6.9 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the right common femoral artery | 8.7 |

| Minimum luminal diameter of the left common femoral artery | 8.4 |

Further anatomical evaluation revealed an uncommon vascular configuration, consisting of three right renal arteries and two left renal arteries. This anatomical variation was critical in preoperative planning and influenced the surgical strategy. Bilateral renal in situ reimplantation was performed to facilitate the placement of an aortic endoprosthesis. The patient was placed in the supine position under balanced general anesthesia combined with neuraxial blockade, a supra- and infraumbilical midline incision was made to gain access to the abdominal cavity, and dissection was carried out in layers to expose the midline structures and the aneurysmal abdominal aorta. The renal hilum was approached first on the right side, located posterior to the aneurysmal sac. Anatomical findings included an anteriorly positioned renal vein and three polar right renal arteries. The arteries involved with the aneurysm and the aneurysmal sac were excluded, with a warm ischemia time of 5 min. Attention was then directed to the left renal hilum, which was located in its typical anatomical position. The renal vein was situated anteriorly, while two polar renal arteries with early bifurcation coursed posterior to the aneurysmal sac. These arteries, along with the left aneurysmal sac, were also excluded, with a warm ischemia time of 6 min. Reimplantation involved anastomosing the three right renal arteries and the renal vein to the external iliac artery, which presented with atheromatous changes. The same procedure was performed on the left side, with two renal arteries and one renal vein reimplanted. All vascular anastomoses were performed using 6–0 Prolene sutures (Fig. 4). The renal reimplantations were carried out in collaboration with the urology team. Cold ischemia times for each renal unit are summarized in Table 2.

Intraoperative view showing bilateral renal arteries and vein reimplantation to the external iliac arteries.

| Kidney . | Cold ischemia time . |

|---|---|

| Right | 4 h 50 min |

| Left | 3 h 30 min |

| Kidney . | Cold ischemia time . |

|---|---|

| Right | 4 h 50 min |

| Left | 3 h 30 min |

Values are expressed in minutes for each renal unit.

| Kidney . | Cold ischemia time . |

|---|---|

| Right | 4 h 50 min |

| Left | 3 h 30 min |

| Kidney . | Cold ischemia time . |

|---|---|

| Right | 4 h 50 min |

| Left | 3 h 30 min |

Values are expressed in minutes for each renal unit.

In the immediate postoperative period, the patient developed hemodynamic instability and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), requiring low-to-intermediate doses of vasopressors. Postoperatively, the patient developed a transient elevation in serum creatinine, peaking at 7.77 mg/dl on postoperative Day 2, consistent with acute kidney injury stage 3 according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Due to persistent anuria lasting 9 days, continuous renal replacement therapy with ultrafiltration at 30–50 ml/h was initiated. Progressive improvement was observed thereafter, with creatinine levels returning to near-baseline values by the fifth postoperative week. The trend in renal function parameters is summarized in Table 3. A renal Doppler ultrasound confirmed patency of the arterial anastomoses without evidence of thrombosis or flow impairment. Intravenous diuretic therapy was maintained until renal function began to improve on postoperative Day 9.

| Time point . | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) . | Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dl) . |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.85 | 11.2 |

| Postoperative Day 1 (POD 1) | 6.10 | 34 |

| Postoperative Day 2 (POD 2) | 7.77 | 45.1 |

| Postoperative Day 3 (POD 3) | 5.93 | 36.4 |

| Postoperative Day 4 (POD 4) | 4.63 | 25 |

| Postoperative Day 6 (POD 6) | 4.17 | 38.5 |

| Postoperative Day 7 (POD 7) | 4.40 | 49.5 |

| Week 2 | 4.36 | 44 |

| Week 3 | 1.32 | 28.2 |

| Week 4 | 1.22 | 10.0 |

| Week 5 | 1.14 | 9.4 |

| At discharge | 1.01 | 8.8 |

| Time point . | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) . | Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dl) . |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.85 | 11.2 |

| Postoperative Day 1 (POD 1) | 6.10 | 34 |

| Postoperative Day 2 (POD 2) | 7.77 | 45.1 |

| Postoperative Day 3 (POD 3) | 5.93 | 36.4 |

| Postoperative Day 4 (POD 4) | 4.63 | 25 |

| Postoperative Day 6 (POD 6) | 4.17 | 38.5 |

| Postoperative Day 7 (POD 7) | 4.40 | 49.5 |

| Week 2 | 4.36 | 44 |

| Week 3 | 1.32 | 28.2 |

| Week 4 | 1.22 | 10.0 |

| Week 5 | 1.14 | 9.4 |

| At discharge | 1.01 | 8.8 |

The patient presented a transient acute kidney injury during the first postoperative week, with peak serum creatinine of 7.77 mg/dl on postoperative Day 2. Progressive improvement was observed thereafter, reaching near-baseline renal function (1.01 mg/dl) by the time of discharge.

| Time point . | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) . | Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dl) . |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.85 | 11.2 |

| Postoperative Day 1 (POD 1) | 6.10 | 34 |

| Postoperative Day 2 (POD 2) | 7.77 | 45.1 |

| Postoperative Day 3 (POD 3) | 5.93 | 36.4 |

| Postoperative Day 4 (POD 4) | 4.63 | 25 |

| Postoperative Day 6 (POD 6) | 4.17 | 38.5 |

| Postoperative Day 7 (POD 7) | 4.40 | 49.5 |

| Week 2 | 4.36 | 44 |

| Week 3 | 1.32 | 28.2 |

| Week 4 | 1.22 | 10.0 |

| Week 5 | 1.14 | 9.4 |

| At discharge | 1.01 | 8.8 |

| Time point . | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) . | Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dl) . |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.85 | 11.2 |

| Postoperative Day 1 (POD 1) | 6.10 | 34 |

| Postoperative Day 2 (POD 2) | 7.77 | 45.1 |

| Postoperative Day 3 (POD 3) | 5.93 | 36.4 |

| Postoperative Day 4 (POD 4) | 4.63 | 25 |

| Postoperative Day 6 (POD 6) | 4.17 | 38.5 |

| Postoperative Day 7 (POD 7) | 4.40 | 49.5 |

| Week 2 | 4.36 | 44 |

| Week 3 | 1.32 | 28.2 |

| Week 4 | 1.22 | 10.0 |

| Week 5 | 1.14 | 9.4 |

| At discharge | 1.01 | 8.8 |

The patient presented a transient acute kidney injury during the first postoperative week, with peak serum creatinine of 7.77 mg/dl on postoperative Day 2. Progressive improvement was observed thereafter, reaching near-baseline renal function (1.01 mg/dl) by the time of discharge.

During his ICU stay, the patient received comprehensive multidisciplinary care, including continuous hemodynamic monitoring, sedation and analgesia, metabolic support, and antimicrobial therapy with meropenem and linezolid. His clinical condition improved progressively, allowing transfer to the intermediate care unit after 2 weeks. There, he continued receiving coordinated care, including physical rehabilitation. Several complications occurred during hospitalization. A unilateral ureteral stenosis was managed with placement of a double-J ureteral stent. The patient also developed hospital-acquired pneumonia, which was successfully treated with targeted antibiotics. Additionally, he experienced abdominal sepsis secondary to an intra-abdominal fluid collection, which resolved following percutaneous drainage and antimicrobial therapy.

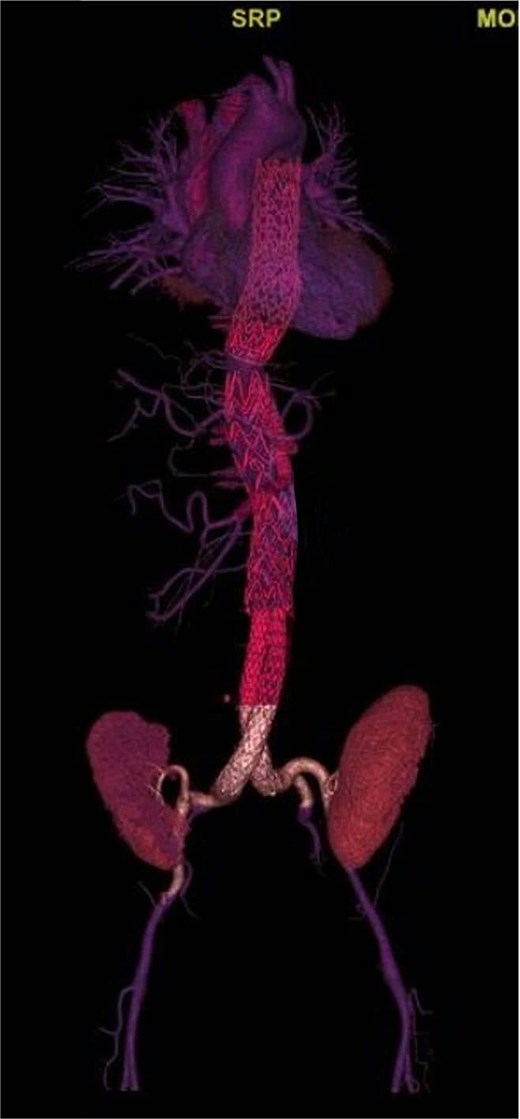

After 43 days of hospitalization, the patient underwent successful placement of a physician-modified endograft (PMEG) based on a 30/26 mm straight Zenith® endograft (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), designed for two-vessel revascularization (celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery). Preoperative planning was performed using 3mensio Vascular™ software (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, The Netherlands), and bridging stents included VBX and BeGraft devices (8 × 39 mm and 8 × 37 mm for the celiac trunk; 6 × 59 mm and 6 × 57 mm for the superior mesenteric artery). The endograft was successfully deployed (Fig. 5) without intraoperative or postoperative complications (Figs 6 and 7). The patient recovered well and was discharged home in stable condition.

Preoperative planning and configuration of a physician-modified endograft (PMEG) for a complex aorto-visceral aneurysm repair. The schematic shows branch positioning and angulation for target vessels, including the celiac trunk (CT) and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), with detailed measurements such as take-off distances, clock-face orientation, and aortic diameters. Planned bridging stents include 8 × 39 mm VBX and 6 × 59 mm VBX for the CT and SMA, respectively. Case plan components, vessel coordinates, and device sizing for main body and fenestrations are displayed. CTA-based measurements and 3D reconstruction aided in customization of the graft for optimal alignment and sealing.

Postoperative three-dimensional CTA reconstruction showing complete exclusion of the aortoiliac aneurysmal sac after endovascular repair. The endograft extends from the distal descending thoracic aorta to the bilateral common iliac arteries, with proper device expansion and preserved distal perfusion.

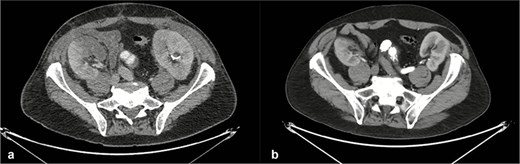

Axial computed tomography images of the thoracoabdominal region obtained before (a) and after (b) endovascular aortic repair. Postoperative imaging demonstrates patent renal arteries with preserved bilateral renal enhancement, consistent with maintained renal perfusion and function.

Discussion

The concept of renal in situ reimplantation was first introduced by James Hardy in 1963 during the management of a ureteral injury secondary to an aortic surgical procedure [1]. Although renal in situ reimplantation remains a relatively rare and debated intervention, it is considered indispensable in specific clinical scenarios. Its primary indications include complex ureteral pathology, renovascular diseases, and select renal neoplasms [2].

In the setting of complex vascular conditions, renal in situ reimplantation has been proposed as an effective solution in cases such as intricate renal artery aneurysms, fibromuscular dysplasia, Takayasu arteritis, and atherosclerotic disease [3]. When less invasive strategies—such as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or endovascular stenting—are not feasible or are contraindicated, particularly in cases involving distal segmental or intrahilar arterial branches, in situ reimplantation becomes a viable alternative [4].

Chiche et al. [5] reported a series of 68 cases in which renal in situ reimplantation was performed to treat renovascular conditions including fibromuscular dysplasia (34 cases), Takayasu arteritis (26 cases), and atherosclerosis (8 cases). Long-term outcomes demonstrated 5-year survival rates of 54% in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and 94%–96% in those with fibromuscular dysplasia or Takayasu arteritis.

Renal in situ reimplantation remains a valuable therapeutic strategy in patients with complex aneurysmal disease, particularly when anatomic factors preclude the use of off-the-shelf or customized endovascular devices [6]. In the present case, the presence of multiple renal arteries arising directly from the aorta made the design of a patient-specific aortic endograft unfeasible. The complexity of the disease warranted consideration of total aortic replacement with visceral reimplantation—a high-risk procedure associated with prolonged operative time. Given the patient’s age and comorbidities, in situ renal reimplantation emerged as a practical and effective strategy to enable subsequent endovascular treatment of the remaining visceral branches. Although future reinterventions may be required, this approach significantly reduces overall surgical morbidity and provides a durable intermediate solution in anatomically challenging cases.

Conclusion

Renal autografting has been described as a treatment option in select cases of renovascular disease, including complex and extensive aortoabdominal aneurysms. Although technically demanding, this approach is effective in preserving renal function and extending patient survival. Its indications are highly specific, particularly in scenarios where vascular reconstruction is required to enable the placement of an endoprosthesis within the aneurysmal segment. We conclude that this type of surgical intervention is feasible in specialized centers such as ours, where a multidisciplinary team ensures that complex hybrid procedures can be performed with the highest standards of safety and patient care.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the staff of Christus Muguerza Alta Especialidad, Monterrey, México.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethics statement

Institutional review board approval was not required for a single-patient case report in our hospital Christus Muguerza Alta Especialidad, Monterrey, México, and the report was prepared in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines [7].

This case report was not required to be registered on a research registry.