-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Bruno Matos Santos, Alexis Poirier, Michaël Racine, Guillaume Meurette, Christian Toso, François Cauchy, Intraoperative left hepatic branch artery aneurysm rupture discovered during cholecystectomy: a case report of a rare and potentially lethal diagnosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1111, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1111

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) is a rare but potentially lethal condition, accounting for ~20% of visceral aneurysms, with a reported rupture rate of up to 44%. Its pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, though risk factors include atherosclerosis, trauma, infection, connective tissue disorders, and iatrogenic causes. Clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic to abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, or biliary obstruction. Angiography-CT is the diagnostic modality of choice. Management is guided by symptoms, aneurysm size, and rupture status, ranging from observation to endovascular or surgical interventions. We report a case of hemoperitoneum due to a ruptured HAA that was incidentally discovered during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Introduction

Hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) is an uncommon (0.002%–0.4%) but life-threatening condition. Despite its rarity, HAA is the second most common type of visceral aneurysm, accounting for ~20% of splanchnic aneurysms and is associated with a reported rupture rate of up to 44% [1–3]. The pathophysiology is not completely understood, but the literature describes several risk factors, such as atherosclerosis, trauma, infection, connective tissue disorders, and iatrogenic causes. The natural history remains unclear, ranging from asymptomatic to abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and biliary tract obstruction [3–5]. Angiography-Computed Tomography (CT) is crucial for the detection of HAA and its complications [3, 4, 6, 7]. Management strategies lack near consensus and are dictated by symptoms, aneurysm size, and rupture status, varying from observation to endovascular or surgical interventions [5]. In this paper, we report a case of an incidental hemoperitoneum caused by a ruptured HAA during laparoscopic cholecystectomy [8].

Case report

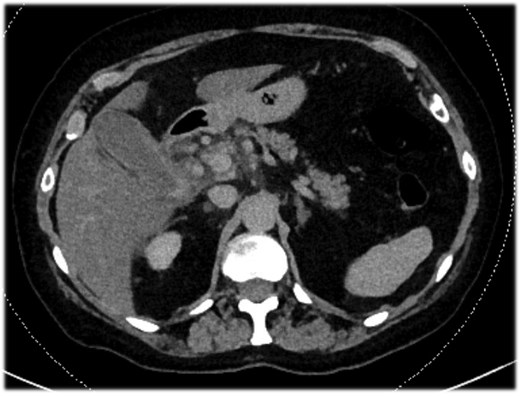

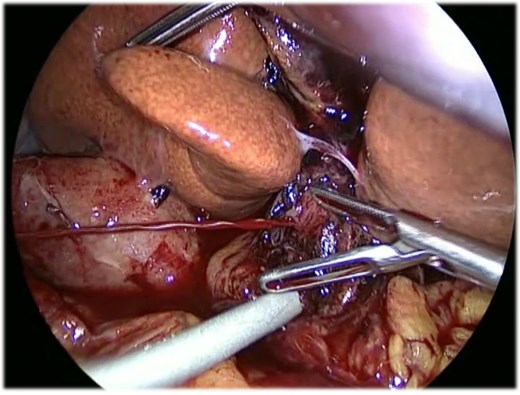

An 82-year-old female presented with a 10-day history of upper right quadrant pain, vomiting, and fever. Her medical history included an appendectomy during infancy and ongoing treatment with Euthyrox and antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg per day). Upon admission, she was presented with fever (38.1°C) and exhibited a positive Murphy sign. Laboratory tests indicated an elevated white blood cell count (WBC) of 13 G/l and an elevated C-reactive protein of 115 mg/l. CT scans revealed features of acute calculous cholecystitis (Fig. 1). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was indicated. Intraoperatively, a perihepatic hemoperitoneum was immediately observed alongside sclero-atrophic calculous cholecystitis. Careful removal of clots on the hepatic pedicle unraveled a massive spontaneous arterial bleeding, which required immediate clamping of the artery and conversion to open surgery (Fig. 2). During the procedure, the bleeding was found to originate from a ruptured aneurysm of the left branch of the hepatic artery. Repair of the artery was neither possible nor relevant given the fragility of the arterial wall. Consequently, the left branch of the hepatic artery was excised along with the aneurysm. Cholecystectomy was performed, and cholangiography results were normal. Due to the atypical nature of the clinical situation, a comprehensive assessment was conducted postoperatively during the hospital stay. The arterial anatomopathological analysis showed no specific abnormalities. A whole-body arterial angiography-CT revealed various arterial malformations of the renal and carotid arteries, in addition to another aneurysm of the gastro-duodenal artery. The angiological workup revealed no other abnormalities, and no evidence of mycotic infection was found. The postoperative course was marked by transient cholangiopathy of the left liver, as evidenced by marked hepatic cytolysis and cholestasis (AST 3471 U/l, ALT 2450 U/l, ALP 175 U/l, GGT 365 U/l, total bilirubin 70 μmol/l, conjugated bilirubin 65 μmol/l), which showed clinical and biological improvement following a 7-day intravenous antibiotic therapy with Ceftriaxone and Metronidazole. She was discharged on postoperative day 11. At 1-month follow-up, both clinical status, laboratory parameters, and CT scan confirmed a favorable evolution, with normalization of liver function tests and arterial vascularization of the left liver through the right branch of the hepatic artery without any features of ischemic cholangiopathy.

Abdominal-CT of patient at admission, revealing signs of acute calculous cholecystitis.

Intraoperative laparoscopic image showing massive spontaneous arterial bleeding on the hepatic pedicle before vascular clamping and conversion to open surgery.

Discussion

HAA is the second most common visceral aneurysm [5, 8–10]. Extra-hepatic HAAs occur more frequently, involving ~40% in the common or proper hepatic artery and 50% in the right hepatic artery. In contrast, involvement of the left hepatic artery is comparatively less common [9]. The majority of visceral hepatic aneurysms are true single aneurysms and are often associated with atherosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, hereditary connective tissue disorders, or malignancies. In contrast, false or pseudoaneurysms can be caused by pancreatitis, post-traumatic, or in cases of previous surgical or intervention procedures [4, 11, 12]. The risk of rupture is particularly high in pseudoaneurysms and has been reported to range from 14% to 80% [7]. Most of the HAAs are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally through imaging. Nevertheless, they can be symptomatic with abdominal pain or the classic but infrequent Quincke’s triad—right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and hemobilia—observed in 25%–30% of cases, which carries a high risk of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding [1]. Angiography-CT remains the imaging modality of choice. According to the Society of Vascular Surgery, treatment is recommended for all symptomatic aneurysms, regardless of size, asymptomatic true aneurysms exceeding 2 cm, expanding more than 0.5 cm annually, or larger than 5 cm in patients with severe comorbidities [5]. The choice of the therapeutic approach is primarily dictated by aneurysm location, collateral hepatic perfusion, and patient hemodynamic status. Whenever feasible, endovascular techniques are preferred because of their lower morbidity. In case of intrahepatic aneurysms, selective embolization is particularly effective. However, in aneurysms of the proper hepatic artery, open surgical repair with arterial reconstruction may be warranted to preserve hepatic arterial inflow and prevent hepatic ischemia [13, 14]. Surgical treatment of ruptured HAAs can be considered when: (i) the patient is in an unstable condition; (ii) the location is extra-hepatic; (iii) endovascular intervention fails; and (iv) the aneurysm or rupture recurs despite multiple interventions. Surgical options include resection of the aneurysm with revascularization or ligation with or without bypass, depending on the availability of collateral circulation and liver function [5, 15].

This case concerns an incidental perihepatic hemoperitoneum resulting from a ruptured aneurysm involving the left branch of the hepatic artery during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. To our knowledge, no literature describes a spontaneously ruptured aneurysm of the left branch of the hepatic artery or its management guidelines. In our case, due to the perioperative condition and massive arterial bleeding, which appeared macroscopically fragile and could not be reconstructed, aneurysmal resection with removal of the left branch of the hepatic artery was decided and performed. Intraoperatively, hepatic ultrasound revealed no signal from the left liver. The postoperative course was marked by transient ischemic cholangiopathy of the left liver, which eventually resolved because of to the collateral hilar plate arterial revascularization. Despite discovering a polyaneurysmal condition during the etiological screening, anatomopathological, angiological, and infectious workups did not identify any clear etiology. This case highlights the unpredictable nature of HAA and its potential complications.

Conclusion

HAA is an uncommon but serious condition, particularly in the event of rupture. We report a case of successful vascular and aneurysmal resection. The absence of a clear consensus on the optimal management of such aneurysms highlights the need for individualized, meticulous, multidisciplinary clinical judgment, and follow-up.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Bruno Matos Santos; Methodology, Bruno Matos Santos; Validation, Bruno Matos Santos, Alexis Poirier, Michael Racine, Guillaume Meurette, Christian Toso and François Cauchy; Formal analysis, Bruno Matos Santos; Investigation, Bruno Matos Santos; Resources, Bruno Matos Santos; Data curation, Bruno Matos Santos; Writing—original draft preparation, Bruno Matos Santos; Writing—review and editing, Bruno Matos Santos, Alexis Poirier Michael Racine, Guillaume Meurette, Christian Toso and François Cauchy; Visualization, Bruno Matos Santos, Alexis Poirier Michael Racine, Guillaume Meurette, Christian Toso and François Cauchy; Supervision, Michael Racine, Guillaume Meurette, Christian Toso and François Cauchy; Project administration, Bruno Matos Santos. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest, financial, or otherwise, that could influence bias.

Funding

No funding was needed for this care report.

References

- angiogram

- atherosclerosis

- abdominal pain

- aneurysm

- ruptured aneurysm

- cholecystectomy

- connective tissue diseases

- hepatic artery aneurysm

- hemoperitoneum

- hepatic artery

- intraoperative care

- rupture

- signs and symptoms, digestive

- surgical procedures, operative

- wounds and injuries

- infections

- diagnosis

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- aneurysm of visceral artery

- biliary obstruction