-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Zhun Shen Tan, Syed Hussein Fathi Bin Syed Mahmud Shahab, Marjmin Osman, Adzim Poh Yuen Wen, Mohd Helmi Mohd Samathani, Nur Asmarina Muhammad Asri, Azrina Syarizad Kuthubul Zaman, Cultural imperative, surgical challenge: salvaging a buried penis in a 9-year-old post circumcision skin loss, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1095, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1095

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Male circumcision is common in Muslim-majority Malaysia but can pose risks when penile anomalies such as buried penis go unrecognized. We report a 9-year-old obese Malay boy with a pre-existing buried penis who underwent routine circumcision. Due to his condition, the initial procedure left an uncircumcised appearance, prompting a revision circumcision. This led to total loss of the shaft skin, resulting in trapped penis with penile skin infection. On presentation, he was febrile with erythematous suprapubic skin. He underwent surgical release, anchoring of the penile shaft, and shaft skin reconstruction using a fenestrated split-thickness skin graft from the thigh. Three months postoperatively, he showed satisfactory urinary and erectile function with minimal contracture and good cosmetic outcome. This case highlights the importance of timely recognition of penile anomalies by healthcare providers and traditional practitioners, appropriate referral, and surgical options for reconstruction following complicated circumcision, especially in high-demand settings.

Introduction

Circumcision is performed either for religious purposes or to treat medical conditions including balanitis, phimosis, and obstructive uropathies [1]. In Malaysia’s Malay Muslim community, ritual circumcision is common in children, holding cultural and religious significance [2]. Circumcision techniques include, among others, bipolar diathermy, dorsal slit, and guillotine technique [2].

High demand often results in procedures being performed by traditional healers or general practitioners rather than paediatric surgeons, leading to higher complications rates as there may be poor patient selection [3, 4]. Reported complications include postoperative bleeding, wound infection, skin necrosis, glanular injury, urethral narrowing, and as in our case, significant preputial skin loss associated with failure to recognize presence of underlying buried penis [5].

A buried penis is defined as the concealment of the normal penile shaft beneath suprapubic fat and skin [6]. Obesity as seen in our patient, represents a well-documented exacerbating factor, due to the resulting prominent suprapubic fat pad [6]. Surgical intervention following complications affecting appearance are often reserved for cases demonstrating significant functional or psychological impairment [7].

The complications of failed circumcision in children [8] highlight the need for better education on recognizing penile anomalies such as buried penis [9]. Clear guidelines for case selection and referral pathways for high-risk cases should be established.

Case report

A 9-year-old obese Malay boy with allergic rhinitis and hypertrophic adenoids was referred for a ‘trapped’ penis 2 weeks after ritual circumcision performed at a general practitioner clinic. On postoperative day (POD) 1, he was able to pass urine but complained of dysuria. His father also noted the glans was covered by suprapubic skin (Fig. 1). Despite reassurance and advice for daily retraction, the appearance remained ‘uncircumcised’ A revision under local anaesthesia was performed at the same clinic but failed as the glans could not be visualized due to adhesions to preputial skin and the procedure was abandoned.

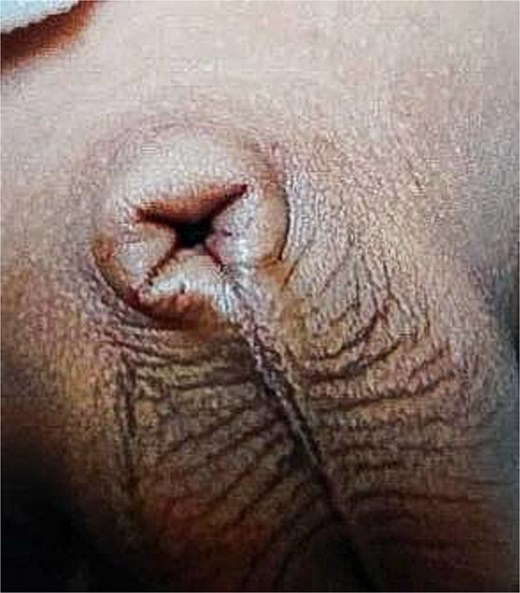

Appearance of penis following initial circumcision the glans was covered and unable to be visualized.

On presentation to our hospital, the patient was alert, conscious, and febrile (38.7°C), with otherwise stable vital signs. The penis was not visible, with the glans and shaft buried beneath erythematous, oedematous suprapubic skin (Fig. 2). Minimal clots and tenderness were present at the area with residual shaft and suprapubic skin. The abdomen was soft, bladder non-palpable, and both testes were in the scrotum.

Preoperative photograph of penis following revision circumcision the glans and shaft was unable to be visualized. Findings include a slit surrounded by erythematous and oedematous skin.

The patient was admitted for 4 days of monitoring and treated with intravenous antibiotics and daily wound dressing to treat the associated skin infection which developed after surgery performed at the clinic prior to definitive plastic reconstructive surgery planned. The patient continued to be able to pass urine normally. One week later after skin infection improved, the patient underwent reconstructive surgery.

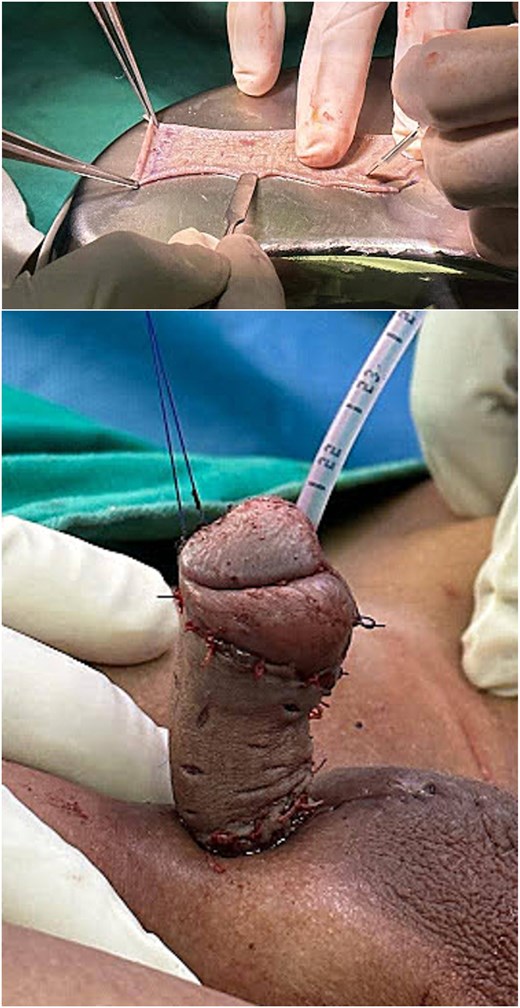

Under general anaesthesia with epidural support, the penis was released from adhesions and scar tissue. Following release of the glans penis, a 10F Foley catheter was inserted, The residual shaft skin at the base of the penis was secured to ensure proper alignment (Fig. 3).

Penoscrotal anchoring with a stay suture at the dorsal side of the glans.

A split-thickness skin graft (STSG) was harvested from the right anterolateral thigh and after fenestration, was anchored to the glans with 4/0 Vicryl (Fig. 4). A modified box dressing using Bactigras, flavin-soaked gauze, and sponge was applied around the base and corona to prevent graft shearing (Fig. 5).

STSG harvested from the right anterolateral thigh was fenestrated and subsequently anchored to the glans penis.

Modified circumferential box dressing applied to the grafted skin around the penis.

Postoperatively, the donor site was dressed with a hydrocolloid dressing, and the patient was advised to remain supine. The box dressing was removed on POD 8 which showed good graft uptake and a clean wound. The indwelling urinary catheter was removed on POD 10 and the patient was able to pass urine normally (Fig. 6). He was discharged home with topical antibiotics. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient showed satisfactory recovery progress with fully healed wounds, normal urination and erectile activity unaffected by the graft. Both parent and child were satisfied with the functional and cosmetic outcome.

POD 7 photograph of the penis, with good graft take and no infections noted.

Discussion

In view of the rising prevalence of childhood obesity, buried penis has become an increasingly common condition that can complicate circumcision if not recognized [10]. Our case demonstrates that if standard circumcision techniques are applied to patients with buried penis, this will result in excessive skin removal [11]. This highlights an educational gap, emphasizing the need for better training to recognize high-risk anatomy and refer appropriately [12]. The delayed referral in our case compounded by an unsuccessful salvage attempt underscores the need for clear practice guidelines in this culturally sensitive context where ritual circumcision is often performed by practitioners without formal surgical training [12].

Our 9-year-old required prompt surgery to prevent fibrosis, skin scarring, infection [7], and psychological distress [13]. A scrotal advancement flap was initially considered as it provides optimal vascularization [14], however, the patient’s Tanner Stage 1 status and thick prepubic fat required an alternative approach. A full-thickness skin graft, although preferred for their greater elasticity and reduced primary contraction, will result in donor-site morbidity that is undesirable in young patients [15]. Hence, we selected anterolateral thigh STSG for its lower visibility of donor-site scarring.

At 3 months, the patient showed satisfactory outcomes without chordee. This case advocates for preventive strategies including body mass index screening prior to circumcision and centralized complication reporting. Future efforts should aim to improve surgical training and health literacy, balancing cultural values with patient safety in Malaysia [2].

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the value of early recognition and prompt surgical correction of buried penis following circumcision, particularly among obese children. Given the cultural importance of ritual circumcision in Malaysia, practitioner education on identifying penile anomalies is essential to uphold safety and reduce psychosocial impact.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

Funding

No financial support was received for this work.

Data availability

All data related to the content of this case report are present within the body of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

This case did not involve any human experimentation, and as such, ethical committee approval was not required. Written informed consent was nevertheless obtained from the patient featured in this report.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent for treatment and for the collection and processing of clinical data for scientific purposes was obtained from the patient and his parents.