-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Immanuella Owusu-Ansa, Robbie El-Bazouni, Zoe Molino, Connor Hirst, Deme Karikios, Sarah Johnston, Femi E Ayeni, An evolving pathology: colorectal cancer with metastasis to the axilla; the treatment approach and response, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1072, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1072

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Colon adenocarcinoma is a well-studied surgical pathology with a streamlined treatment regimen. The typical areas of disease metastasis include liver and lungs, however, there have been reports of unusual locations of disease spread. This includes metastases to the breast, thyroid and testes, which often lead to deferral from conventional treatments. An 83-year-old female presented to her general practitioner with dizziness, fatigue, and altered bowel motions. Subsequently, a surgeon is confronted with this case of mucinous adenocarcinoma with axillary metastasis, diagnosed by FluoroDeoxyGlucose (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography (PET) with Computed Tomography (CT) and confirmed with biopsy. Her tumour was found to be both microsatellite instability/mismatch repair (MSI/MMR) deficient and KRAS A146V positive. How should this influence treatment? We discuss this pathology, its treatment implications, as well as a brief literature review. This is the first case of metastatic colorectal cancer to the axilla in Australia and the only reported of such cases in literature with both MSI/MMR deficiency and KRAS146V mutation.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality has decreased significantly in the last two decades according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. This has been attributed to the introduction of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Programme and more effective treatments [1]. CRC driven by genomic alterations has guided the development of personalized molecular medicine, leading to better treatment responses [2–5]. Unusual locations of disease spread of colon adenocarcinoma have been reported in the literatures [6–9].

Mucinous adenocarcinoma is a histological variant of colon cancer, accounting for ~10%–15% of total CRC cases. It commonly occurs in patients with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch Syndrome, and is frequently associated with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI) tumours [10].

Microsatellites are products of mismatched DNA repairs [11, 12] and are biomarkers of mutation whilst KRAS is a gene which codes for cell division and proliferation. Both MSI and KRAS mutations are being investigated for the prognostic stratification and personalized treatment of CRC [5, 6, 11, 12].

Case presentation

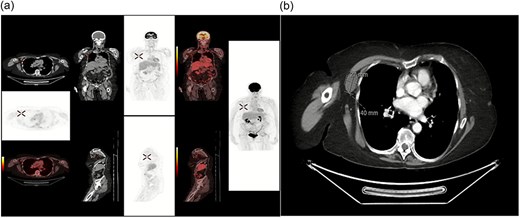

An 83-year-old female independent from home, with a history of multiple resected melanomas and basal cell skin cancers, presented to her general practitioner with a few weeks' history of fatigue, dizziness, and altered bowel motions. Initial CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a 42 mm lobulated lesion within the mesenteric fat medial to the caecum and terminal ileum, with subsequent colonoscopy revealing two sessile polyps in the rectum and descending colon, which were resected. She proceeded to ileocolic resection, followed by a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for an incidental bulky mesenteric mass on CT. Interestingly, nodal pathology showed mucinous adenocarcinoma with no clear primary despite a second surgery with full bowel run, as well as a full endoscopy. Other laboratory investigations included full blood count, liver function tests, tumour markers, C-reactive protein, and a computed tomography of her abdomen and pelvis. Time from diagnosis to treatment was 2 years (Fig. 1). Three months later, PET imaging demonstrated an enlarged right axillary lymph node, which was subsequently resected (Fig. 2). Histopathology confirmed mucinous adenocarcinoma.

(a) FDG PET/CT showing hypermetabolic focus in the right axilla, consistent with metastatic disease from a colorectal primary tumour (confirmed with biopsy) (b) CTAP showing incidental right axilla mass.

Surgical and oncological treatment

She underwent laparoscopic ileocolic resection complicated by high-grade small bowel obstruction. Four months later she had axilla pain which was confirmed as metastasis and commenced on Pembrolizumab. Four cycles of three-weekly pembrolizumab were started: guided by the KEYNOTE 177 Trial. Follow up CT 3 months after immunotherapy showed progression of the axillary lymph node from 2 cm to 2.8 cm. Due to possible pseudo progression, treatment continued with two more cycles of three-weekly pembrolizumab and an additional two cycles of six-weekly regimen (changed for patient’s convenience). Follow-up CT showed further axillary lymph node enlargement, therefore pembrolizumab was ceased and underwent axillary lymph node clearance and is currently under surveillance.

Pathology and micrographs and investigations

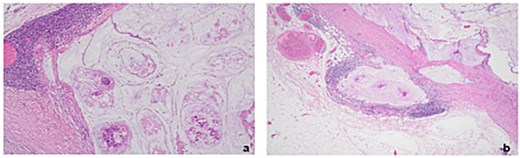

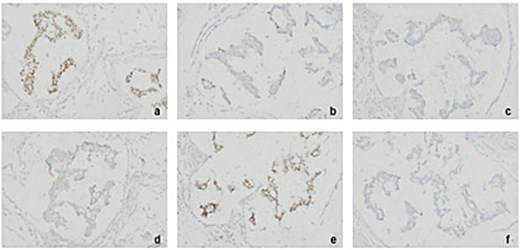

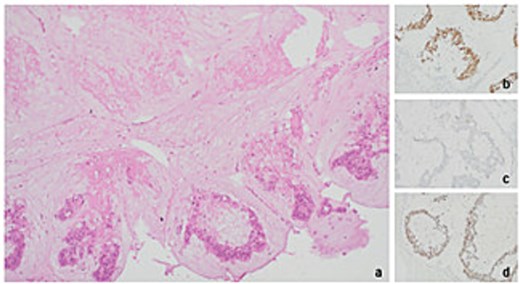

Histopathological analysis of the excised ileocolic mass showed mucinous adenocarcinoma, with serosal infiltration. Out of 22 lymph nodes, three were positive for metastases. Immunohistochemical analysis of mismatched repair genes showed microsatellite instability-low (MSI-L), with loss of MHS6 staining (Figs 3 and 4). Histopathology of axilla lymph nodes suggested metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4), with positive staining for CDX2 and SATB2 (Figs 5 and 6) in favour of malignancy of primary colorectal origin.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for mismatch repair proteins in right hemicolectomy sample at 20× magnification. (a) MLH1 retention in tissue (b) MSH2 retention in tissue. (c) MSH6 loss observed in tissue (d) PMS2 retention in tissue.

Histopathology of excised right axillary lymph nodes. (a) Malignant acinar architecture with high levels of extracellular mucin indicative of mucinous adenocarcinoma (Haematoxylin & eosin stain at 10× magnification) (b) Extranodal expansion of mucin into capsule (Haematoxylin & eosin stain at 4× magnification).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for various tumour markers in excised right axillary lymph nodes points towards colorectal origin of tumour (at 20× magnification). (a) CDX2 positive (b) CK20 negative (c) ER negative (d) Napsin-a negative (e) SATB2 positive (f) TTF1 negative.

Histopathology of level 1 lymph node from right axillary clearance pointing towards metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of colorectal origin (a) tumour present with necrosis (Haematoxylin & eosin stain at 10× magnification) (b) CDX2 positive (20× mag.) (c) CK20 negative (20× mag.) (d) SATB2 positive (20× mag.).

Axilla lymph node resection showed clearance at levels 1–3. Two level 1 nodes, 10 level 2 nodes and 16 level 3 nodes were excised. The largest level 1 node (49 × 37 × 30 mm) displayed complete architectural effacement, with extracellular mucin, hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei, abnormal mitoses, and apoptosis consistent with a metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of colorectal origin (Fig. 6), with positive KRAS A146V. Seven level 2 nodes and all level 3 nodes were free of any evidence of metastatic disease. Other initial investigations, including full blood examination, C-reactive protein, liver function tests, urea creatinine, and electrolytes were all unremarkable.

Discussion

Colorectal cancer has been traditionally defined by its tissue of origin, but it is now better understood as a heterogenous disease with three genome pathways [2, 3, 5]. Chromosomal instability pathway, MSI/MMR deficient pathway and CpG island methylator phenotype pathways are responsible for genetic instability in CRC. Understanding these pathways and formulating drugs to suppress them is the new focus of CRC treatments [2].

This is an extremely rare case of lymph node metastasis of colorectal cancer with both chromosomal instability and MSI/MMR deficiency. A literature search on PUBMED and MEDLINE showed eighteen previously reported cases of colorectal cancer with axillary metastasis (Supplementary Material 1). Of note, our case is the first reported in Australia and the only case with both MSI/MMR deficiency and KRAS146V mutation.

The tabulated results presented (Supplementary Material 1) demonstrate not only the widespread histological subtype associated with axilla metastases, but also that there were no reported gene mutations in most of the cases. Treatment response varied with FOLFOX and FOLFIRI. BRAF V600E and MSI were reported in 3 of the 18 cases. Only one of the three went into remission after conventional chemotherapy (Supplementary Material 1).

The conventional treatment of CRC is usually surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy; with formulations like 5-Fluorouracil and folinic acid (FOLFOX), as well as modified 5-Fluorouracil, Leucovorin and Irinotecan (FOLFORI) [5, 6]. Unfortunately, half of these patients have recurring lesions which are difficult to resect and refractory to the same treatment [5]. Immunotherapy has been shown through several clinical trials to be more effective for MSI/MMR-positive patients [6] whilst anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR are being studied as treatment therapies for KRASA146V positive cancers [2]. The KEYNOTE 177 TRIAL showed pembrolizumab was more effective in MSI CRC and had little side effects. Also, patients who were refractory to FOLFOX and FOLFIRI responded well to pembrolizumab [4].

Conclusion

Is metastatic colorectal cancer an evolving pathology? This case with two unique genetic mutations poses this question. The genetic mutations also have different treatment recommendations that make it challenging to manage. Although the patient presented did not respond well to pembrolizumab but perhaps her unique mutations will guide future research, making multi-genomic alterations a focus in future clinical trials.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Consent

The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this case report.

References

- positron-emission tomography

- fluorodeoxyglucose f18

- computed tomography

- mutation

- lung

- biopsy

- colorectal cancer

- dizziness

- fatigue

- adenocarcinoma, mucinous

- australia

- axilla

- intestines

- neoplasm metastasis

- surgical pathology

- physicians, family

- breast

- liver

- neoplasms

- pathology

- testis

- thyroid

- metastasis, axillary

- adenocarcinoma of colon

- mismatch repair

- k-ras oncogene

- microsatellite instability

- colorectal cancer metastatic

- kras2 gene